Going into the past in search of wrongs could lead to the discovery of innumerable injustices that conceivably demand contemporary rectification.

Do We Long for Rest—or Power?

Whether we know it or not, we live in preparation for dying. The choices we make, the people and objects toward which we display our love and devotion, and the manner in which we spend our time form that preparation. As Jocko Willink is fond of pointing out, that time is always running out.

Prior to the pandemic, for most Americans, ordinary life involved a comfortable orbit between home and work, and strenuous efforts to avoid contemplating the passage of time too deeply. Death unsettles this state of affairs. We try to deny its dominion over us. We structure our society around delaying it at almost all costs, and tend to shield ourselves from looking too closely as it arrives to claim our loved ones. One acquires the sneaking suspicion that we consequently don’t know much about how to die—or how to remember those who have passed.

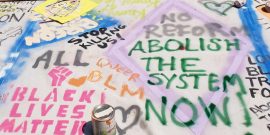

Consider one relatively recent shift in how some people now memorialize the dead: “Rest in Power.” The phrase first appeared in public about twenty years ago courtesy of Oakland, California’s graffiti culture. In the last few years, it has become a more widely-used phrase of choice for those on the left to remember the dead. Last September, Slate’s Rachelle Hampton lamented the phrase’s increasing “overuse,” and the threat that it might become diluted to the point of meaninglessness. But her explanation of why the phrase became popular is striking:

What rest in power offers mourners of Dream and Tupac Shakur and Sandra Bland over rest in peace is the chance for a senseless death to matter in a way that a life could not. It is the coda to the refrain of no justice, no peace, a phrase that was similarly vaulted to the national stage in the wake of Ferguson, whose roots also lie in the wake of racially motivated vigilante violence.

As Hampton observes, “rest in power” suggests possibilities of meaning tied to the protest slogan, “no justice, no peace.” At the surface level, it evokes the idea that the truly woke dead cannot know peace until justice comes, and that the bearers of their memory should discover inspiration for the struggle from their death.

Consider first the demand for justice. The cry of “no justice, no peace” reflects a partial truth: without a measure of justice, civic peace becomes an impossibility. But we must balance justice against other goods and virtues that make for a decent life in common: forgiveness, order, prosperity, equality, honor, civility. The woke instead pursue a justice monomaniacally defined by equality. This issues in a quest to eradicate inequalities produced by markets, classes, racism, sexism, and every other form of discrimination, real or imagined.

Our republic was founded upon a human—and therefore flawed—love of both liberty and justice. In Federalist 51, James Madison wrote that “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” The trouble with the new woke vision of justice is not just that it threatens to fulfill Madison’s prophecy, but that it demands too much of politics entirely. It finds expression as a kind of justice subsumed under equality, where not even the dead can find respite and history itself must be turned into a political weapon. Justice, presented as the opposite of peace and allied only with power, cannot bring about reconciliation—it only prolongs and exacerbates our civic conflicts. Untrammeled justice in this sense becomes little more than a cover for a politics of vengeance.

The familiar phrase that “rest in power” replaces dates back at least two thousand years, and finds expression in both Jewish and Christian memorials to the dead. The peace that the faithful pray finds the departed is obvious, but even a secular stoic could offer the condolence in honesty. If life is suffering and struggle, its absence brings peace. “Rest in peace” suggests that perfect contentment cannot be found on this earth, and hints that only our true destination can provide it. Theists of all stripes can offer “rest in peace” as a condolence to the bereaved, regardless of their status—for it implies a hope that lies beyond human control.

If the old saints and martyrs could be remembered as pilgrims and wayfarers, what does “rest in power” tell us about the new ones? In a brief reflection on the new logic, Sohrab Ahmari notes that by contrast, the new condolence cannot simply be offered to just anyone. He quips that to the woke, it is better that some of the dead “rest without power—if at all!” This suggests that we ought to understand “rest in power” as an honorific meant to be bestowed only upon the worthy or the unjustly slain—and that judgment is entirely a matter of politics.

There’s a line crossed here, one between honoring the dead in and of themselves—and for their deeds—the other side of which dragoons the dead into ongoing service.

That we need to memorialize the dead says something about the inescapability of our moral natures, but the desire for power tends to pervert that nature. In saying that “rest in power” offers a “chance for a senseless death to matter in a way that a life could not,” Hampton offers us a clue about how it distorts our sensibilities: Without a justice-oriented political purpose, life itself is drained of meaning.

There’s a line crossed here, one between honoring the dead in and of themselves—and for their deeds—the other side of which dragoons the dead into ongoing service. When Lincoln told the audience at Gettysburg that in dedicating the battlefield as a final resting place that they should “highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain,” he drew a sharp moral distinction between the finished work of the fallen and the continuing work of the living.

By contrast, rather than recognizing the hallowing effect of death, and the sanctity of memory, “rest in power” implies that we must remember the dead primarily in terms of the present’s perceived political needs. The phrase offers a picture of memory that casts aside the notion we might imitate the dead, learn from their mistakes, or grow in wisdom from understanding their lives. Implicitly, this means that we remember only the useful, and actively efface the memory of those whose lives oppose “justice” in some respect.

That this entire line of thinking reflects a fundamental mistake can be seen in the simple self-contradiction of rest and power. Are not rest and power opposites? Power ever yearns for control. Bertrand de Jouvenel likened it to a devouring Minotaur, forever seeking more. Rest inhabits a different conceptual universe, one where we sleep, play board games or sports with our kids, take vacations, and just exist without striving. To offer the condolence “rest in peace,” recognizes the finitude of all human projects. It justly affirms a domain beyond the political.

To demand that rest and power coexist reflects an act of will, not reason, and a love of power that demands totalizing control over human life. Dealing with radicals of a similar political ardor, Edmund Burke wrote that “they deny even to the departed, the sad immunities of the grave…. Their turpitude purveys to their malice; and they unplumb the dead for bullets to assassinate the living.” The search for power over the present demands that no corner of life remain undisturbed.

Mobilizing the dead to “rest in power”—to ask that their name itself conjure power—invites dysfunctional politics to invade every remaining aspect of life. How can we be good neighbors or friends if we evaluate everyone we encounter, living or dead, on solely political grounds? In that way, not only liberty dies, but also the possibility that anyone can find a measure of earthly rest.