Ten years after her passing, Ostrom's work remains vital.

Rethinking Thinking

You find yourself in a bar, deeply engaged in a discussion with a friend over a public policy issue. You hold your position with confidence, convinced beyond doubt that there’s no room for debate. Every article you have read, every news segment you have watched, and every conversation you have had in the past month regarding this issue has reinforced your stance. In your mind, you are right, and your friend is mistaken. The evidence, as you see it, is undeniable. Why, then, does she fail to acknowledge what seems to be so clear?

However, it dawns on you that she’s not alone in her perspective. In fact, most experts in the field stand on her side of the argument. This realization prompts a critical question: how could so many knowledgeable individuals overlook what you perceive as obvious? If this scenario sounds familiar, there’s a strong possibility that you have fallen victim to confirmation bias: a tendency to seek out, interpret, prefer, and remember information in a manner that affirms your existing beliefs or values.

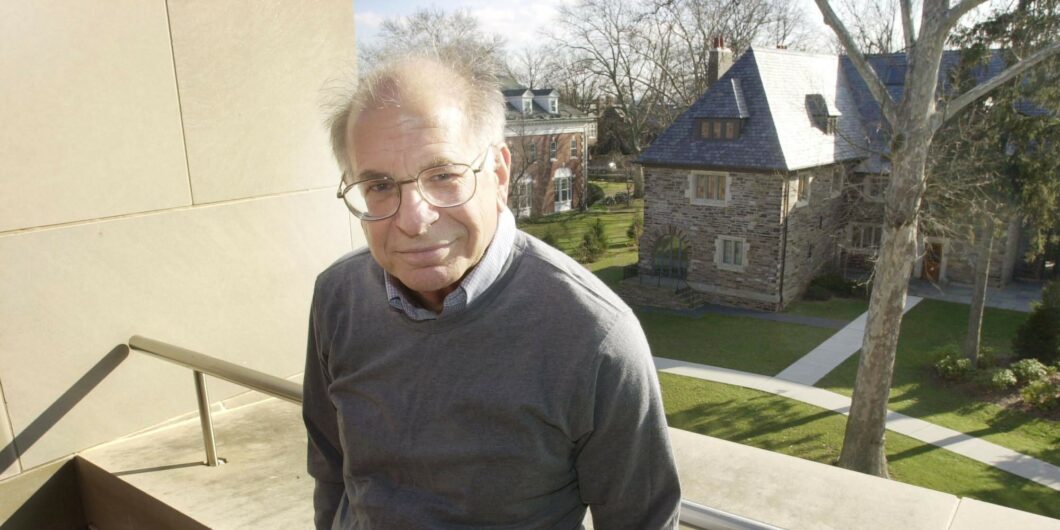

The examination of this and other cognitive biases and their impact on human decision-making is at the heart of behavioral economics, a field pioneered by Daniel Kahneman, whose recent passing marks the end of an era in this domain. In his work, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 (along with Vernon Smith), Kahneman was challenging the traditional concept of homo economicus—a cornerstone upon which classical economic theories and models are constructed.

According to Kahneman, human behavior deviates significantly from perfect rationality. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, which encapsulates decades of research in behavioral economics, Kahneman argues that decision-making is governed by two distinct systems: System 1 and System 2. System 1 functions automatically and effortlessly, with little or no sense of voluntary control. It is responsible for intuitive judgments and immediate decisions via mental shortcuts or heuristics. In contrast, System 2 is slow and analytical. It demands our conscious control and is engaged in complex decisions requiring significant mental effort.

We often view ourselves through the lens of System 2: as beings of reason who base our choices on rational thought. Yet, in reality, we rely on System 1 far more frequently than we might believe, leading to consistent and predictable mistakes, i.e., cognitive biases. Kahneman, in collaboration with his colleague Amos Tversky, delves into these heuristics and biases, often using experimental methods in his research.

When making decisions, we tend to overestimate the importance of readily available information (availability heuristic); rely too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter (anchoring bias); draw conclusions from small samples of data (law of small numbers); ascribe more value to things simply because we own them (endowment effect); value losses more than equivalent gains (loss aversion), a principle central to Prospect Theory developed by Kahneman and Tversky; and overestimate our abilities and performance (overconfidence bias), among other noted biases.

His background in psychology helped Kahneman shed light on the real-world nature of decision-making, which often diverges from expected utility calculations.

A recent literature review on the effects of cognitive biases on investment decision-making may help illustrate our human tendency to succumb to these systematic errors. According to the literature, investors exhibit a home bias when picking stocks, are often prey to herding, and hold on to losing positions for too long (disposition effect). Furthermore, investors often exhibit overconfidence in their capacity to outperform the market. This is evidenced by the significant portion of investors who continue to actively manage their portfolios or invest in actively managed funds, despite the failure of most funds to consistently beat the market over the long term.

His background in psychology helped Kahneman shed light on the real-world nature of decision-making, which often diverges from expected utility calculations. In fact, decisions are frequently driven by simple heuristics, i.e., mental shortcuts human beings use to make fast and often biased decisions. Recognizing and mitigating these biases can help both individuals and businesses make more informed decisions that lead to better and more efficient outcomes.

For instance, an employer in a sector traditionally dominated by men might not hire a highly qualified female candidate due to an unconscious adherence to the stereotype of what a successful employee should look like (representativeness heuristic). In a competitive market, employers free from such biases can capitalize on overlooked talent, hiring the most competent candidates regardless of gender or other irrelevant factors.

Recognizing our inherent biases in decision-making raises policy questions— and here things get more controversial among those skeptical of government intervention. Should governments step in to enhance decision-making processes? The idea that public institutions should influence behavior in beneficial directions while still upholding freedom of choice has been given the provocative appellation “libertarian paternalism.” Nobel laureate Richard Thaler and his coauthor Cass Sunstein introduced and elaborated on this concept in their bestseller Nudge.

The central idea of Nudge is simple yet has sparked considerable debate. Kahneman, Tversky, and others have shown people are susceptible to a range of systematic biases that may result in less-than-ideal decision-making. Thaler and Sunstein argue that individuals can be subtly influenced—or nudged—towards less biased choices that improve their overall well-being.

One example lies in retirement planning policies. Concerns about inadequate retirement savings are widespread due to present bias: the inclination to prioritize immediate needs at the expense of future well-being. In response, many countries have adopted automatic enrollment policies for retirement savings programs in an attempt to nudge employees into saving for retirement. For instance, the 2006 Pension Protection Act in the United States allows employers to automatically sign up their employees for 401(k) plans. However, employees retain the option to opt-out or alter their contribution level.

Though Kahneman made serious contributions to our understanding of individual decision-making, the field of behavioral economics and its practical applications have faced notable criticism. One key point of contention is the perceived overemphasis on irrationality in decision-making, using the homo economicus as a straw man to critique more nuanced contemporary economic models. This intense focus on irrationality might have also led researchers to identify biases where there is none, a phenomenon some authors call a bias bias.

In addition, critics argue that, even if cognitive biases influence our choices, there’s little evidence to suggest these biases have a negative impact on health, wealth, or happiness. One reason explaining this might be that learning from our errors may help us identify and correct our biases. Although this is often true, persistent biases like overconfidence in investment decisions suggest that, at least in some instances, this correction does not occur. If this were the case, biases could arguably lead to negative outcomes such as lower long-term wealth.

A second reason concerns the usual methodology used to identify and analyze biases: experiments. Indeed, another area of criticism targets the replicability and generalizability of experimental findings in behavioral economics. Steven Levitt and John List from the University of Chicago have raised concerns that behaviors observed in laboratory settings may not accurately reflect actions in real-world scenarios. This would help explain why cognitive biases do not always have negative effects, highlighting the gap between experimental conditions and real-world behaviors.

Nudging has been criticized on ethical grounds since such interventions might be manipulative, subtly prompting individuals into making choices deemed superior by policymakers. Moreover, it assumes that those designing nudging strategies (termed choice architects by Thaler and Sunstein) are themselves acting rationally. But are not academics and regulators alike also subject to their own sets of biases, incentives, and behavioral tendencies?

Despite these criticisms, it is important to recognize that Kahneman exerted a profound influence in both the academy and the public arena. By integrating psychological insights into the realms of economics and finance, he shed light on aspects of human behavior that were previously overlooked or undervalued.