Should conservatives recapture American higher education or start anew?

Second Thoughts on My Younger Self

Profundity of thought belongs to youth, clarity of thought to old age.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Young people, who are still uncertain of their identity, often try on a succession of masks in the hope of finding the one which suits them—the one, in fact, which is not a mask.

W. H. Auden

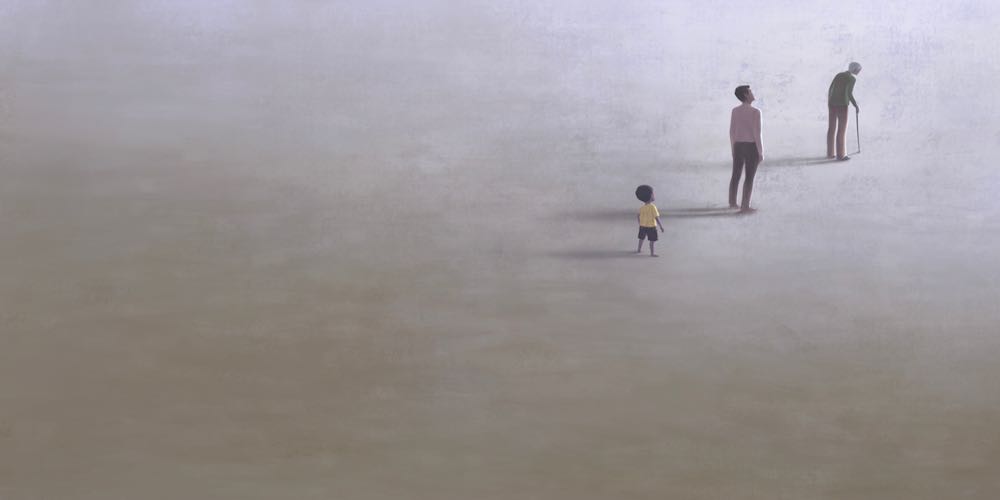

Sometimes it is a bit painful to read something that I have written, especially if it is from some time ago. Looking at the topic I chose or the approach I took in essays of years past, I wince a little. Or roll my eyes. Why did I care so much about that issue? How did I come to such a conclusion? Couldn’t my approach have been more succinct or less sanctimonious? This, I guess, is the curse of every serious writer. Even more, it is the curse of every maturing adult considering aspects of his or her younger self.

Time, however, slow though it is, has a way of purifying. Facts emerge. Interests morph. Tones soften. Attitudes change. We, fundamentally, change. Once willing to “go to the wall” for some issue, we are now unwilling to get out of our chairs. William F. Buckley, citing “great embarrassment at the immaturity of my expression,” called the re-reading of his classic God & Man at Yale (in preparation for a twenty-fifth-anniversary introduction) singularly “uninviting.”

In an essay (To Criticize the Critic) critiquing his own work (and his own naive youth), T. S. Eliot sheepishly acknowledged what he didn’t know and what he could have done better in his earlier writings. He even lamented being haunted by decades-old quotes attributed to him as if he had only said them yesterday (Twitter users, beware). Had he not grown, matured, or simply changed (even for no good reason) since his original writing? Shouldn’t the earnest and honorable writer employing an Eliot quote confirm with him, “Do you still feel this way?” Chased by his own work, the glum Eliot quoted Percy Bysshe Shelley:

And his own thoughts, along that rugged way,

Pursued, like raging hounds, their father and their prey.

But are we surprised by this? Our younger selves strained for significance and liberty through our fresh ideas, lofty crusades, and unflagging certainty. Our statements were more exclamatory than declarative, more mic drop than dialogue. The player had come to play and impatiently shooed the deliberative souls into the bleachers where they belonged. When we were young, we were (as an anonymous genius observed), “Often wrong, never in doubt.” We had not yet arrived at Oscar Wilde’s epiphany: “I’m too old to know everything.” But this youthful vim and vigor have potential blowback. “Conviction without experience,” Flannery O’Connor warned, “leads to harshness.” For any reflective adult, looking back will always be a bit of a cringer.

In a line famously misattributed to Mark Twain, we get to the heart of our younger selves: “When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much he had learned in seven years.” In his song, My Back Pages, Bob Dylan offers a similar illustration:

Crimson flames tied through my ears

Rollin’ high and mighty traps

Pounced with fire on flaming roads

Using ideas as my maps

“We’ll meet on edges, soon,” said I

Proud ’neath heated brow

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now.

It is an enlightening experience to read Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. Well over a century ago, Franz Xaver Kappus, a young German poet in a hurry, dashed off a charmingly effusive and impatient letter to the aged (twenty-six years old, mind you) and established poet Rainer Maria Rilke. While we only have the privilege of reading Rilke’s responses, it is clear that young Kappus is fervent about shortcutting his way to success. “Here are my poems,” he seemed to restively ask, “What do you think?” Rilke, with what was surely a saddened, sympathetic brow, offered little advice in the way of mechanics, and more in the way of how to live a life.

Nobody can advise you. Nobody. There is only one way. Go into yourself. … Dig down into yourself for a deep answer.

Allow your verdicts their own quiet untroubled development which like all progress must come from deep within and cannot be forced or accelerated. Everything must be carried to term before it is born.

You are so young, all still lies ahead of you, and I should like to ask you, as best I can, dear Sir, to be patient towards all that is unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms, like books written in a foreign tongue. … Live the questions for now. Perhaps then you will gradually, without noticing it, live your way into the answer, one distant day in the future.

Something changes with age—something we cannot rush or master—and that something is experience and judgment. And it isn’t easy. A mentor once said to me, “Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment.” Aging economist John Maynard Keynes, accused of an inconsistency respecting his previous theory, asked (in a brilliant, but likely apocryphal quote), “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” And the master tragedian Aeschylus bluntly tells us, “He who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.” A quarter of a century after his warm correspondence with Rilke, the aging Franz Xaver Kappus would reflect with time-spent wisdom, “Where a great and unique person speaks, the rest of us should be silent.”

Because as we age, if we are paying attention, we should become a bit more humble, a touch more precise, a hair more circumspect (just read Cicero’s On Old Age). We should do the wise things and leave off the stupid ones. In so doing, our work gains the measure and authenticity of the soldier in the trenches that are, at times, lost by the general in the map room. We come to know the gritty amid the transcendent, and the mucky amid the sublime. In essence, we understand the way things are and not simply the way things ought to be. And it happens, in time, drop by bloody drop.

Having second thoughts about my younger self, I can’t help but shake my head and smile. I would do and say and write so many things differently. And yet, I am grateful that I can’t. I just had to learn. And grow.

“What a fool,” I muse, “and what a joy.”