The Fracturing of Spanish Politics

On Sunday, July 23, 2023, Spaniards went to the polls to vote in the country’s national election. The result is an inconclusive mess—and a cautionary tale for the rest of us.

This followed regional elections in May of 2023, in which the Conservative Party, “Partido Popular (PP),” made unexpected and dramatic gains in most of Spain’s 17 autonomous communities. Given that Spanish regional elections are usually harbingers of the national elections that follow, the country’s dashing, photogenic prime minister Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón of the country’s socialist party (PSOE) decided not to wait until December when the general election was scheduled. Instead, he called for a snap election that was held on July 23. His goal was to limit the damage for his party; in addition, Europe was closely watching to see if Spain might take a hard populist right turn as has been the case for—in one way or another—Finland, Italy, Germany, Poland, Hungary, and France.

Sánchez was criticized for calling elections at such a hot time in Spain; many Spaniards, moreover, had already left early for their August vacation. Nonetheless, the stakes were high so turnout was around 70%—even if some voters went to the polls dressed for the beach. One precinct reported a voter arriving in scuba gear.

Sánchez’s opponent was Alberto Núñez Feijóo of the PP who hails from the northwest autonomous community of Galicia, having as its capital Santiago de Compostela. He is a political moderate and a competent manager, though he lacks Sánchez’s charisma. The conservatives were expected to win a convincing majority in Spain’s parliament, the Congreso de Deputados.

Instead, they imploded. Spanish politics are complicated so this takes a bit of explaining.

Sánchez’s strategy worked far better than he expected. Although PP bested PSOE in the popular vote, it fell short of the support necessary from minor parties to reach a 176 majority in the 350-seat parliaments; PSOE has a much better chance of forming a new government and holding on to power.

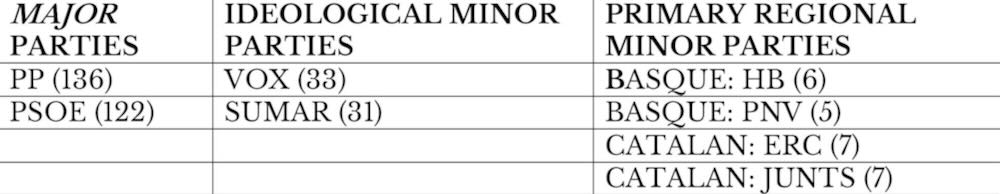

Spain’s minor parties fall into two categories: ideological and regional. The largest minor parties are the ideological “Sumar” (“to bring together”) on the hard left, and “Vox” (“Voice”) on the right. The biggest loser, Vox, on whom the PP depends for support, lost no less than 19 parliamentary seats from the 2019 national election.

Other minor parties include two regional parties from Catalonia (Junts and ERC), and two from the Basque Country, (PNV and EH Bildu). The smaller regional parties are BNG (Galicia), UPN (Navarre), and CC (Canary Islands).

Here is a breakdown of Spain’s parties and the parliamentary seats each party now controls:

Spain’s current ideological parties can only be understood in light of the Los Indignados movement in 2011, when the shift to a multi-party system began. Los Indigados means “the indignant ones.” They are mostly young citizens who think the prevailing political parties no longer serve them, so they chant “no nos representan”—they don’t represent us. I happened to be at the University of Santiago de Compostela in 2011 when a colleague invited me to take a walk to the city’s Plaza Mayor. There we encountered several dozen tents whose occupants were haphazardly arranged in various groups, sitting akimbo and earnestly discussing politics.

Los Indignados inspired “Occupy Wall Street” but whereas the American episode produced little more than fresh fodder for comedian Stephen Colbert, Los Indignados provoked a change in Spain’s political landscape, so much so that Spain has not had a majority government since 2015. The movement first gave a big boost to the Spanish left, spawning a new Marxist party, “Podemos” (“We Can”). Several of the leaders are students of Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci and admirers of the late Hugo Chavez of Venezuela. Podemos, in turn, provoked a new right-wing party, “Vox” (Voice), which received the third most votes in the recent election. Podemos, though, had a short life, as it performed poorly in the regional elections in May 2023 and suffered from instability in the party’s leadership. Thus it appeared that the Spanish left was on the wane.

If Spain is a bellwether, even beyond Europe, then, the election suggests that those who run to the far left or the far right may leave voters disenchanted if not disgusted. The Spanish election also suggests that no electoral system is perfect.

An interesting thing happened, however, on the way to the elections. After the regional elections, dynamic politician Yolanda Diaz, raised in a staunchly communist household, created a new political platform, Sumar. After Sanchez called the snap elections, Diaz took Sumar to the next step, making Sumar a political party rather than just a platform, absorbing Podemos as well as several small leftist parties. Consequently, PSOE cannot form a coalition without Sumar, and PP cannot without Vox.

With respect to the regional parties, the important ones come from the Basque autonomous community and from the Catalonia autonomous community. Each region, moreover, has two notable parties. In the Basque region, leftist EH Bildu (Euskal Herria Bildu) is the successor to Herri Batasuna, which was the political face of ETA, the terrorist organization in the Basque Country. Their relationship was analogous to the erstwhile partnership of Sein Fein and the IRA. Like the IRA, ETA has grown weary of assassinations, kidnapping, and blackmail—after all, violence is hard work.

Herri Batasuna, however, was outlawed so that the more radical Basques moved the vegetables around the plate and formed EH Bildu, whose membership includes many former members of Herri Batasuna. The other Basque political party with a national presence is PNV (Partido Nacionalista Vasco) whose heritage is conservative and Catholic. This party has heretofore been willing to support PP, but in this election, has been put off by Feijóo’s rhetoric. The two Basque parties together control a total of 13 seats in the Congreso.

The Catalan parties are the most controversial and the most critical in achieving a majority in the Congress. The leader of Junts, Carles Puigdemont, fled the country when the government began rounding up those who staged the illegal referendum for independence in 2017. Junts has struck a hard bargain for their support for PSOE. They demanded another (unconstitutional) referendum on independence as well as (an unconstitutional) amnesty for those who spearheaded the referendum.

Thus, as conservative and liberal Spanish newspapers alike ruefully note, the fate of Spain’s government led by PSOE depends on successful negotiations with a fugitive from justice who wants to dismember the country. More generally, the two major parties that occupy the left-of-center and right-of-center moderate ground, representing the majority of Spaniards, cannot govern without a policy of constant appeasement to the most extreme elements in Spanish politics.

So, why did things go so unexpectedly wrong for the conservative Partido Popular in the July elections? The primary reason has to do with PP’s alliance with Vox.

Sanchez’s most effective strategy was to tie the PP under Feijóo’s leadership to Vox at every opportunity, especially in the only debate between the two candidates. This has put Feijóo between a rock and a hard place, or, as the Spanish prefer, between the sword and the wall. Sanchez knew, as everyone else knew, that PP would not be able to govern without Vox. At the same time, Feijóo had to disassociate himself from Vox as much as possible but with a wink and a nod, hoping to retain Vox’s support.

Some of Feijóo’s supporters unwisely employed the slogan “Que te vote Txapote, Sanchez.” It means, in effect, “Let Txapote vote for you, Sanchez, because we will not.” “Txapote” is the alias of a Basque terrorist convicted of murder but now associated with EH Bildu. It counts among its membership a number of former terrorists, including those convicted of murder—but who have now completed their sentences. The slogan, however, backfired as it proved so offensive to families of ETA victims, that the Spanish electoral commission prohibited those with Txapote t-shirts from voting until they changed. In their debate, Sánchez asked Feijóo to disavow the slogan but Feijóo was evasive.

Vox’s leader, Santiago Abascal, made no effort to disguise his intentions, for example, when the party put up a campaign banner in Madrid showing a hand dropping waste in a trash can. The pieces of waste are labeled, variously, “EU,” “feminismo,” and “LGBTQ+.” A Vox official callously declared that domestic violence no longer exists in Spain, but all know that “machismo” still lurks behind closed doors. Sometimes it is public: even the women’s national soccer team was bullied. At the conclusion of Spain’s remarkable women’s World Cup Soccer win on Sunday, August 20, Luis Rubiales, the President of the Royal Spanish Football Federation, forcibly kissed top scorer Jenni Hermoso (in front of the Queen and her youngest daughter, no less) and then followed Hermoso into the locker room “joking” about marrying her.

He later “apologized” but protested that he only did what was “natural.” Rubiales is now out of a job, but, on August 28, his mother barricaded herself in the “Church of the Divine Pastor” outside of Granada, declaring a hunger strike until those “persecuting” her son leave him alone.

You really can’t make this stuff up.

Although hesitant about unrestrained trans rights, Spaniards are generally libertarian about gay rights. Notably, four of the leading players on the soccer team are lesbian. In respect to the EU, most Spaniards are not eurosceptic, given that European Union largesse, among other things, has transformed Spain’s infrastructure and restored many of its historical landmarks.

Feijóo is not as skillful on the stump as Sánchez. In what may have been semantic confusion, Feijóo accused Yolanda Diaz of “massaging” unemployment figures in Spain. One of the words for massage in Spanish is “maquillar” which also means to put on make-up. So, when Feijóo said that Diaz “maquillaje sabe mucho”—“knows a lot about massaging,” or, “knows a lot about make-up”—Diaz seized the opportunity to tie Feijóo to the anti-feminism of Vox. Whether he was guilty of a sexist remark is not clear—at best it was maladroit.

After the election, the king of Spain, Felipe VI, also found himself between the sword and the wall. He would prefer to ask Feijóo to form a government but that would seem ill-advised because PP probably cannot do so, notwithstanding the popular vote. He would rather not ask PSOE because certain elements in its coalition are anti-monarchical. On Tuesday, August 22, nonetheless, the king made a Solomonic decision and asked Feijóo to form a government because it was “customary” to first ask the party with the most popular votes. Feijóo has until September 26 to do the impossible; absent a PP miracle, Sánchez will then have his chance.

In the meantime, the PSOE was able to gain support from the Catalonians to get their pick for President of the Congreso (compared to the U.S. Speaker of the House) who immediately showed her thanks by declaring that, in addition to Spanish, the constitutionally recognized Catalan, Gallego, and Basque languages will now be spoken (and translated) in the Congreso. Sánchez has already made a token gesture asking the same from Brussels—in addition to the already 24 official European Union languages.

What are the implications of the 2023 election for Spain and beyond? Spaniards are often noted for their good sense (“buen sentido”), a quality perhaps acquired from life in the extremes during the fratricidal Spanish Civil War (1936–39) and the ruthless Franco years (1939–75); the majority thus now lean toward moderation in politics. In the May regional elections, they punished PSOE for its association with the far left, especially Podemos. In the July national elections, many feared that PP would cater to Vox.

If Spain is a bellwether, even beyond Europe, then, the election suggests that those who run to the far left or the far right may leave voters disenchanted if not disgusted. The Spanish election also suggests that no electoral system is perfect. Those in the U.S. who decry the Electoral College because of the occasional incongruity between electoral votes and popular votes might note that the same may occur in parliamentary governments and, worse, may create a kind of political paralysis that does not occur in the U.S. As Hamilton suggested, the Electoral College may not be “perfect,” but “it is at least excellent.” (Federalist Paper #68).

Assuming he fails in forming a government, Feijóo will not be the face of the PP much longer. The only hope for Vox’s long-term survival is to moderate and absorb itself into the Partido Popular. Sánchez is said to have nine political lives: he will be around for a while, but if he fails to wrangle a majority, expect new elections this December.