In the woke world, feelings become sacred.

The Illiberal Giants of Asia

Over the last decade, political pundits have become fixated on a now-familiar pattern derailing democracies around the world: mass, disaffected populists rallying around strongman autocrats—heavy-handed political outsiders with a penchant for eroding liberal institutions. The populist-strongman wave has swept over diverse regions and varied elections, from the Philippines to Hungary to Brazil, just to name a few. NGOs have dedicated wings of their organizations to address the problem; democracy watchdogs have released special reports on the issue; and thought leaders throughout academia, think tanks, and the media have written prolifically on the democratic threat posed by populist movements launching autocrats to power.

But accurate as the populist-strongman formula is for many nations, it obscures more than it illuminates in the world’s two largest countries, where two of the most dramatic—and strategically significant—resurgences of autocracy are occurring. Despite sharing a superficial likeness to the populist-strongman phenomenon, the parallel roots and structure of India’s and China’s descents into illiberalism differ markedly from the populist trends now widely understood elsewhere—and have been almost entirely overlooked.

Rather than mob-like populist masses or lone-wolf strongman individuals, India and China are increasingly under the sway of highly-disciplined, anti-democratic vanguard groups: the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) of India. Together, they represent a distinct, sizeable threat to liberalism: not so much manifestations of the populist-strongman wave as drivers of it—carefully orchestrating mass zeal to fuel their own autocratic ends, and grooming highly effective anti-democratic leaders. With more than a third of humanity living in societies increasingly shaped by CCP and RSS cadres, democracy’s defenders would do well to understand the very different threats to liberalism they represent.

The CCP & RSS

These days, the CCP requires little introduction: Founded in 1921, the Party rose to power out of the chaos of the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Japanese invasion, and the Chinese Civil War, entrenching itself as the powerful governing class of China since 1949. Having weathered the fall of European communism and experimented with a period of relative openness, the 95-million-member party rules China with an iron fist, and now directs the greatest state threat to freedom the world has seen in decades under the leadership of its General Secretary, Xi Jinping.

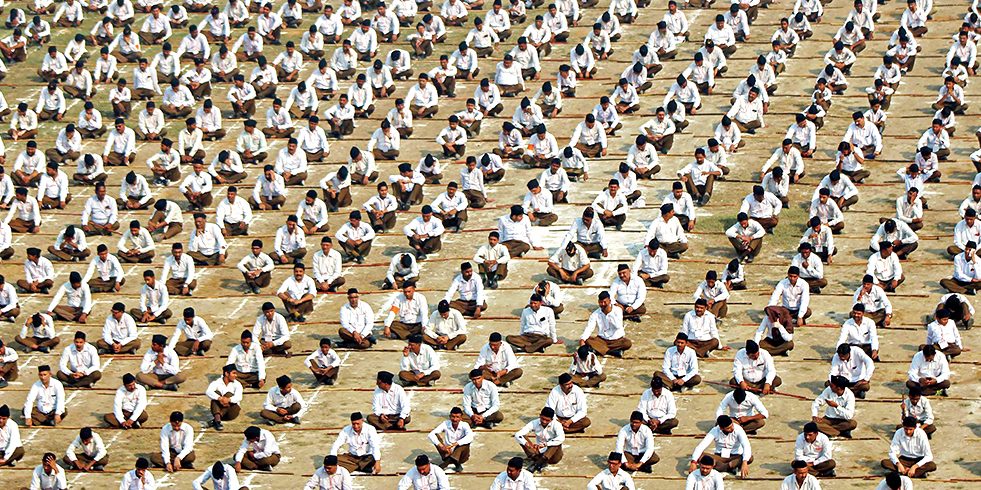

The RSS, by contrast, is little known outside of India, and prefers it that way. Constituted in 1925 in the British Raj as a “character-building” organization, the RSS aimed to cultivate men dedicated to the cause of Hindu nationalism, a right-wing ideology promoting the establishment of a muscular Hindu regime. The Hindu nationalists of the RSS eschewed Gandhi’s peace-loving, conciliatory independence movement in favor of a more assertive approach that excluded what they saw as India’s greatest internal threats: sizeable Muslim and Christian minorities.

Since independence, the RSS has been banned by India’s government on three occasions for reasons of state security. But that has not stopped the organization from successfully spawning the world’s largest political party (currently ruling in India), Hinduism’s premier deliberative forum, and India’s largest labor union, student union, and private school system, among other influential organizations. All of these organizations orbit around the RSS in its mission to realize its vision of Hindu nationalism—with impressive efficiency.

Much differs between the CCP and the RSS, not least the fact that one has run a dictatorial government for more than seven decades, while the other exists in a multiparty democracy. But their resemblances are not difficult to see: Both organizations were constituted a century ago as non-military cadres, with members systematically indoctrinated, sworn to serve their ideologies above all else, and trained to hijack social and political institutions. Both took their early cues, including their cadre structures, from Europe’s 20th-century totalitarian movements: Just as Mao’s Little Red Book stressed that the CCP is a party “built on the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary theory and in the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary style,” so also the RSS’s longest-serving “Supreme Leader” lauded how Nazi Germany manifested “race pride at its highest,” with lessons for “Hindustan [India] to learn and profit by.”

Each has spent decades popularizing selective versions of its nation’s history centered on civilizational humiliation by outsiders and the concomitant need for assertive, heavy-handed rulers. Both aimed not only for political power, but also to refashion their societies’ identity and values according to their radical visions of social order.

But to accomplish their similar goals, they have pursued opposite strategies: the CCP conquered the Chinese state and used its power to induce a rapid, top-down reordering of society; the RSS built strength incrementally as a bottom-up, grassroots movement with a broad range of powerful affiliated organizations spanning every domain of public life—crafting a sort of parallel society that aimed to absorb mainstream institutions.

The upshot of these inverse strategies is a Chinese society that is much more thoroughly under the heel of CCP cadres, but one that is also riddled with the cynicism, corruption, and double-speak you would expect from a relatively small class maintaining a monopoly on both state power and the public sphere. Indian society, meanwhile, has only had the RSS’s viewpoints enter the mainstream in recent years—but with the zeal and confidence of a movement that has won the trust of a huge segment of society from marginalized beginnings. At the time of this writing, the RSS appears poised to further consolidate its power in the absence of any viable opposition, with its political affiliate, the BJP, boasting a whopping 180 million members—more than the total population of Russia. Albeit at very different speeds and through alternative tactics, the RSS and the CCP are both making progress towards similar autocratic visions for their societies.

Authoritarian Regress

Just a decade ago, both the RSS and the CCP seemed well on their way to reform. Having emancipated itself of the economic dimensions of communism, the CCP looked amiable to the prospect of political liberalization, too, and began creating space for greater free expression. Likewise, the political demands facing the BJP led RSS alumnus and former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to retool the party—and the RSS’s organization family behind it—under a more reasonable, conciliatory, and cooperative face. The two groups’ historic connections to communist and fascist movements of the past were deliberately downplayed to their domestic audiences and suppressed to the international community.

But in hindsight, the years of the BJP’s and RSS’s relative opening up are starting to look more like the exception than the rule. With the resurgence of the CCP under Xi and the RSS under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, chilling echoes of the two groups’ European forebearers are beginning to emerge.

In China, Xi has unleashed a series of purges under the auspices of an “anti-corruption campaign” that would give Stalin a run for his money. More than a million Uyghurs have been interned in camps featuring Party indoctrination classes, struggle sessions, and gulag-like forced labor. The state is blanketing public spaces in surveillance cameras, erasing notaries from the public record, and rewriting history books and primary school curricula to stress absolute submission to the Party.

India has also lurched towards authoritarianism, plummeting in democracy ranking indices. Though Modi does not serve as the Supreme Leader of the RSS, he has emerged as the de-facto head of the Hindu nationalist movement which retains the RSS at its heart. Since Modi’s election in 2014, the government has hollowed out federal courts; rewritten election laws to skew political fundraising overwhelmingly in its favor; and taken initial legislative steps that could strip millions of Muslims of their citizenship—not to mention a range of state-level bills designed to further restrict Muslims’ rights and birthrates. Meanwhile, journalists are routinely harassed, attacked, and occasionally killed for criticism of Hindu nationalist views, as street violence against religious minorities becomes endemic.

With the future of both the world’s preeminent autocracy and the world’s largest democracy at stake, failing to understand the unique threat posed by Asia’s illiberal cadres would be a costly mistake.

To be sure, Xi and Modi bear much of the blame for these unwelcome developments. But the CCP and the RSS are still more fundamental to the autocratic patterns that India and China are developing. Xi and Modi represent exactly the sort of men that the CCP and the RSS are designed to cultivate. Both were shaped from a very young age by their organizations, which acted as the primary influence on their outlook and ambitions throughout their lives. Xi has championed Mao’s brutal dictatorship more than any other Chinese leader since Mao’s death—despite his own childhood and family being ripped apart by Mao’s privations. In doing so, he has demonstrated both the ruthlessness and the mind-bending loyalty that the Party expects of its upper echelons. Narendra Modi, for his part, calls the RSS’s most radical Supreme Leader, infamous for his support of the Nazi ethno-state, his “Guru worthy of worship.” Modi built his early political career as an RSS preacher turned “Hindu Supremacist” politician, in the apt words of one 2007 New York Times headline.

In truth, the RSS and the CCP did not just groom Modi and Xi; they also selected them to rule, to differing degrees, for their own interests: Xi, known for being “redder than red” was a deliberate choice of the Party to re-consolidate its internal factions. Modi’s candidacy and landslide victory were predicated on his successful maneuvering between RSS interest groups, as much as his campaigning skill. Both of their political successes were based on their rising through the ranks of the cadres, and skillfully wielding the networks of influence that both have cultivated over decades. In all likelihood, the needs and talent pipeline of the CCP and the RSS will be similarly pivotal in determining both Modi’s and Xi’s successors, as much or more than the populations they will rule over.

The Challenge of the Cadres

To begin to understand the challenges posed by the RSS and the CCP, one might start by considering just how different they are from conventional populist movements. The latter tend to ebb and flow in societies, and typically find homes in political parties that seek to assimilate popular impulses and interests as they evolve. Though particularly dedicated followers might form groups or engage in mob-like violence, such developments are typically ad-hoc and informal.

The RSS and the CCP work the other way around: using extreme methods of socialization and indoctrination, they build a body of intensely loyal operatives that attempt to steer the masses, inducing popular impulses that align with the cadres’ ideologies. In the RSS, for instance, a standing corps of thousands of “pracharaks” forswear wealth, marriage, and home to serve the RSS for the rest of their lives full-time—ready to be dispatched anywhere for the cause of Hindu nationalism. In the CCP, young cadres are deputed across the country to champion the Party’s policies, and can expect tremendous wealth and prestige if they successfully cultivate Party fervor and charm the right Party superiors.

The intense, internal loyalty found in both groups means that they are able to play the long game in promoting narratives and incentives that fall in line with their groups’ visions. It also means that, unlike traditional strongmen, Modi and Xi are able to manipulate all aspects of society with armies of disciplined operatives scattered throughout companies, schools, religious bodies, and the military to drill their leaders’ messages into public life. Where the cadres fail to win influence, both organizations maintain more forceful means of silencing opponents: the Chinese judicial system and secret police brutally manage dissent, just like, on a more limited scale, thuggish networks of Hindu nationalist vigilantes harass, intimidate, and attack foes of the RSS.

Not unlike the cadres of Europe’s 20th century, the RSS and the CCP have been pushing their populations towards dangerous belligerency through a potent combination of zealotry and fear. The growth of Mao revivalists and Red Guard wannabes among China’s youth, and spontaneous pogroms against Muslims in India’s capital two years ago—partially facilitated by the police—are ominous portents of a more unstable, illiberal future for both of Asia’s giants.

To be sure, China under the CCP remains the far greater threat to global democracy today for its cadres’ much tighter grip on society, the vast economic leverage it wields over other nations, its well-developed influence campaigns against open societies, and the comparatively more ruthless tactics it employs at home and abroad. But the potential of the RSS to further derail India’s society, traditionally seen as a beacon of hope for democracy’s potential in the developing world, must not be underestimated as the cadres further entrench their domineering agenda.

Figuring out how to address the threats posed by the RSS and the CCP is a tremendous challenge that will likely involve finding ways to exploit fissures within each groups’ factions, or pioneering methods to mitigate the monopolies on public life that both organizations seek. But for now, those are second-order questions: the first priority needs to be recognition of a consequential, distinct strand of rising illiberalism that differs considerably from the populist-strongman phenomenon that has attracted the lion’s share of attention in recent years. With the future of both the world’s preeminent autocracy and the world’s largest democracy at stake, failing to understand the unique threat posed by Asia’s illiberal cadres would be a costly mistake.