Activists often claim a kind of sacred wisdom about transgender issues. But in the UK, at least, that's now up for debate.

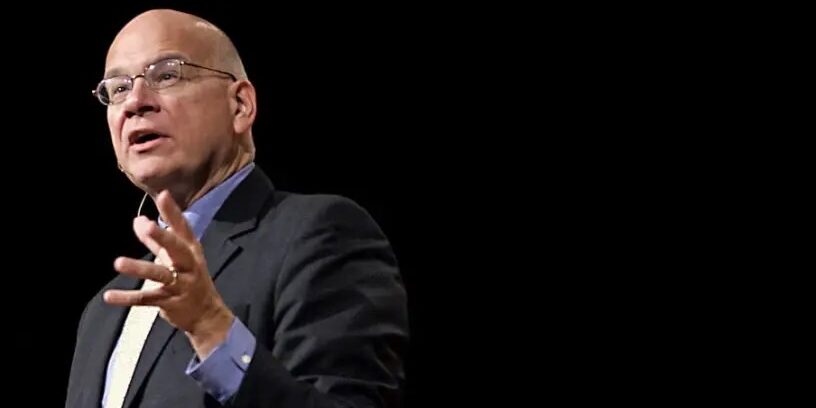

The Importance of Tim Keller

The passing of the Rev. Dr. Timothy J. Keller has caused quite the fervor in the reformed evangelical world. We all hoped against hope and prayed fervently that he would be in the 12% that beats pancreatic cancer. Alas, he was not. In the days that followed his death, it seemed that pastors, ministry leaders, scholars, and laymen alike sharpened their elegiac pencils and gave it their best shot. Some reflections have been quite touching. Some have been cringey photobombs. Regardless, those outside the reformed evangelical world might find themselves puzzled by the overwhelming amount of praise pieces for someone they know very little about.

What made Tim Keller so important to these people? Here are some brief reasons that might help explain the fervor to those outside the reformed evangelical world.

First, Keller made Christian beliefs academically attractive. He had a remarkable ability to synthesize diverse strands of thinking into simple ideas that not only sounded smart but actually were. For reformed evangelicals, this is a dream come true. Outsiders have to understand the pervasive Christian identity for many in this camp. Most feel like academic pariahs, and for the ones that care about this, Keller made them feel less so. He was smart, insightful, and witty. He published extensively. He spoke clearly. He wasn’t afraid. In him, they found a sense of academic validation and progress.

Should reformed evangelicals feel this way? Of course not. They shouldn’t care in the slightest that some academics think poorly of them, nor that a genius among us was finally recognized. After all, the elites thought poorly of Jesus, who taught his followers to love God and love neighbor with whatever gifts he’s given them. That might be academic excellence. Or it might mean academic ridicule. “For so persecuted they the prophets before you.” However, Keller had a way of easing this “burden” by effortlessly navigating academic ideas without losing his orthodoxy, as he did in his The Reason for God. For the many reformed evangelicals that feel like they’re on the intellectual bottom shelf, Keller was a welcomed solution to a perceived problem.

Secondly, Keller had an uncanny way of making even the smallest interaction feel important, and for those that already felt like pariahs, this made unknown people feel like somebodies. Perhaps you’ve noticed that much of the ululating has been in the form of “I remember when Tim called me….” or “In one of our conversations—I can’t remember which—Tim said to me….” You can imagine how that made people feel. Here’s a famous pastor—and a really smart one—that would regularly engage with much-less-known people.

Tim used his extensive people skills and the gift of encouragement to help pastors, leaders, and ministry innovators. But one of the results is that everybody wants everyone to know just how close they were to him. One’s ego is massaged by knowing one is in an inner circle. The Protestant apologist C. S. Lewis himself felt this urge regarding his academic positions. He pointed out the follies of giving in to the strong desire to be counted among an inner circle. It’s part vanity, part pride, part fear. And reformed evangelicals are just as guilty of it as anyone else. But Keller was not the person to fault for this. He was simply a gracious, humble leader that reached out to many, many people. And upon his death, many, many people wanted everyone to know he talked to them.

Third, Keller was a moral role model. He had a successful personal life and ministry without scandal. He and his beloved wife, Kathy, maintained a stable family life in the city that never sleeps without so much as a hint of impropriety. In an era of celebrity pastors and their tragic downfalls, reformed evangelicals are quick to point to him as an ideal role model for both personal and professional life.

Keller succeeded in what so many reformed evangelicals are trying to do: finish their race without becoming shipwrecks. To have a famous pastor and leader succeed in this crucial area meant not only that it’s possible, but that one of us did it. There’s a profound satisfaction and relief in this. God is still completing the work he began in us, even in one of our most famous leaders.

Fourth, Keller defied the odds. Conservative Protestant churches aren’t supposed to survive in downtown Manhattan, but Keller’s did. That fact alone garnered a loyal following because reformed evangelicals love perpetually playing the role of the underdog. The key phrase here is “perpetually playing.” In many cases, reformed evangelicals are not the underdog, but many of them maintain that attitude. This gives them a sympathy card to play and garners further inclusions into inner circles. To see Keller succeed in Manhattan was to see an underdog win the Superbowl.

To do this, he rallied a diverse following in his church and ministries, and as he slowed down in his later years, many others picked up the mantle. Further, his particular Presbyterian ecclesiology meant that many other elders were involved in ministry successes. Yes, he was the figure head, and a really good one, but no one person could pull off what he did. It was a divine work facilitated by many other people.

Keller had a unique way of communicating the Christian faith in fresh ways that helped people both begin and continue their journey in the faith—even through intense suffering like the cancer that ended his life.

Fifth, Keller achieved hero status. In an American culture that at once attacks and elevates heroes, reformed evangelicalism had finally found their man. He was smart, successful, and theologically conservative. He made the New York Times bestseller list. He would draw crowds of thousands to hear him speak. He was sought after for book recommendations. He could exegete texts of Scripture from the original languages. Few in reformed evangelicalism have reached that level of notoriety and respect.

However, Keller was too righteous a man to want hero status. But fandom has a way of spreading without permission from the hero. Such is evidenced by Keller’s enormous following in life and in death. If you’re a somebody in reformed evangelicalism, you have a story of how Keller, like a hero, rescued you from something nefarious like discouragement or obscurity. And that cemented his hero status.

Sixth, Keller shaped culture both inside his camp and outside it, and reformed evangelicals want desperately to shape culture. This is why his “winsome” approach to evangelism became so popular. Reformed evangelicals essentially latched on to his methods and said, “See? I can tell others about Jesus without being weird or mean or uneducated.” Outside his camp, he maintained many relationships with influential people that often sought his advice and friendship.

Keller’s ultimate goal was never to win the culture wars. He wanted people to know Jesus, and he was good at making Jesus look appealing. In turn, many people came to know Jesus through his ministry, and the subsequent results were cultural shifts where people lived, worked, and played. Proximally speaking, Keller is to credit for this. But further upstream, these changes are because following Jesus puts demands on one’s life, not because a luminary in Manhattan turned the cultural tides. This strategy—seeking followers of Jesus and not cultural victories—enabled him to sidestep many pitfalls that other evangelical leaders find themselves mired in.

Lastly, Keller was a spiritual guide. Throughout his decades of ministry, Keller had a unique way of communicating the Christian faith in fresh ways that helped people both begin and continue their journey in the faith—even through intense suffering like the cancer that ended his life. This type of guidance was his gift, and he used it until his dying day. Even his last words compelled people to join him in following Jesus: “There is no downside for me leaving, not in the slightest.”

Reformed evangelicals are rightly grateful for such a guide. The Bible has clear demands for God’s people to be thankful, and the response of gratitude is entirely appropriate. It not only honors Keller but also honors his God. Keller was the first to point out that he was a mere sign post pointing others to Jesus.

In the coming days, much more will be said about the life and death of the Rev. Dr. Timothy J. Keller. Most of it will be praise to God for this wonderful and significant man. Most of it will honor him for being a faithful servant to God and the Church. Some of it will be tinged with the marks of imperfect people that want to both honor him and be seen for honoring him. For now, he has left big shoes to fill and many eager pastors that want to give it a shot. Let’s pray they—and we— are of the same caliber as Keller.