The Liberation of Scrooge

“Can citizens of a social welfare state fully discharge their charitable obligations simply by paying their taxes?” This was the question posed by the late Robert Payton, who helped found the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University and with whom a colleague and I often co-taught a course called Ethical and Religious Perspectives on Philanthropy. His question echoes a theme in one of the most philanthropically influential texts in the English language, Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” a staple of every Christmas season.

“A Christmas Carol” springs from an apparently irresolvable tension. On the one hand, London was the world’s greatest city, the capital of the greatest nation in the world. And yet it was also filled with legions of the poor, wracked by malnutrition and disease, barely subsisting on paltry wages or no wages at all, and often winding up in workhouses and debtors’ prisons. The financial implosion of Dickens’ family when he was a boy acquainted him all too intimately with such a life, yet he could not bear to share the story with anyone, so great was his shame.

Dickens wrote his tale in a matter of weeks, during which he was groaning under financial pressures and taking long, solitary walks around London at night. He had recently read the 1843 “Report of the Children’s Employment Commission,” exposing the dreadful conditions of working-class children. It was a life about which he knew something from his boyhood days working in a boot black factory. He had planned to compose a political pamphlet but was later seized by the idea of a story that would land with “20 thousand times of the force” of what he had initially planned.

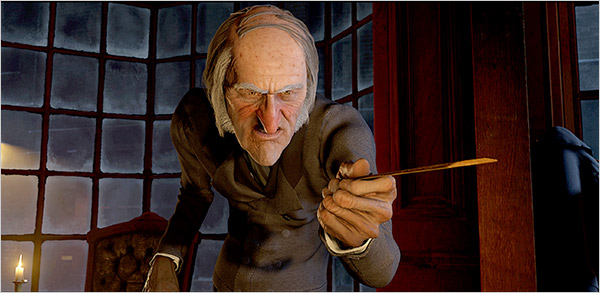

Dickens’ tale is so effective because, in the words of Chesterton, it is targeted not at institutions but “an expression of the human face.” His focus is not a social movement but the transformation of a single heart – that of perhaps the most memorable character of the novelist who created more such characters than any other. The face of Ebenezer Scrooge (“screw” + “gouge”) bears the expression of a “squeezing, wrenching, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner,” a man “hard and sharp as a flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire.”

Whether or not Scrooge resents being forced to pay taxes to support social welfare institutions such as workhouses and debtors’ prisons – and it seems highly likely that he does – he certainly believes that he owes nothing more.

We meet Scrooge on Christmas Eve. Appropriately, he is in his counting house, going over his books. “Secret, self-contained, and solitary as an oyster,” he is visited by his nephew Fred, whose merry greeting he rebuffs gruffly: “If I could work my will, every idiot who goes about with “Merry Christmas” on his lips would be boiled with his own pudding and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.” Next come two charity workers, one of which appeals, “At this festive season, it is more than usually desirable that we make some slight provision for the poor, who suffer greatly at the present time.”

“Are there no prisons?” asks Scrooge.

“Plenty of them,” says the man.

“And the union workhouses?” Scrooge demands, “Are they still in operation?”

“They are,” says the man.

Asked what they can put him down for in the way of a donation, Scrooge responds “Nothing,” adding that he cannot afford to make idle people merry. He helps to support the “establishments” he mentioned, they cost “enough,” and “those who are badly off must go there.” To which the man protests, “Many would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” Scrooge counters, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge’s philosophy is this: The suffering of others is not my business. “It is enough,” he declares, “for a man to understand his own business, and not to interfere with other people’s.” Whether or not Scrooge resents being forced to pay taxes to support social welfare institutions such as workhouses and debtors’ prisons – and it seems highly likely that he does – he certainly believes that he owes nothing more. He is, in this sense, a staunch defender of his own liberty, which to him means the freedom to be left alone. Responsibility for others is a matter in which he takes no interest.

Later that evening in his dark, empty, and chilly home, Scrooge is visited by the ghost of his deceased partner, Jacob Marley, who wanders the earth in chains of greed that he forged in life. He has come to warn that unless Scrooge changes his ways, a similar fate awaits him. Yet Scrooge will hear nothing of it, protesting

“But you were always such a good man of business, Jacob.”

“Business!” cries the ghost, wringing his hands. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business.”

Scrooge lives to accumulate, and he believes that by accumulating more, he is enlarging himself and proving that he has lived as he ought to have done. But the Ghost of Jacob Marley thinks otherwise, and to help Scrooge see anew the life he has led, Marley’s ghost will be followed by ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come. If Scrooge can only survey his life, reconnecting with his sufferings as a lonely boy; witness the impoverished family of his underpaid clerk, Bob Cratchit, and especially his crippled son, Tiny Tim; and see how little his life will have amounted to once it is over – he may yet change.

Of course, Scrooge’s words come back to haunt him. Having witnessed the Cratchit family’s materially paltry yet spiritually rich Christmas dinner, at which Bob offers a generous toast to his boss, Scrooge is moved to ask whether Tiny Tim will live. The Ghost of Christmas Present responds, “I see a vacant seat, in the poor chimney-corner, a crutch without an owner, carefully preserved.”

“No, no” says Scrooge. “Oh no, kind spirit, say he will be spared.”

“If these shadows remain unaltered by the future,” says the ghost, “none will find him here. What then? If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Later, two wretched children emerge from the ghost’s robes. The ghost tells him that they are want and ignorance. “Have they no refuge or resource?” cries the appalled Scrooge.

“Are there no prisons?” says the spirit, turning on him. “Are there no workhouses?”

Scrooge had long stilled his conscience with the thought that the suffering of poor families and children was not his problem. He dutifully paid taxes to support the institutions that handled such matters, resolving not to concern himself any further with it. But the opportunity to view the broad trajectory of his life and see for himself where it would end up leads him to see things differently. He realizes that he has not lived as he ought to have done – that though his coffers are full, his life has been deeply impoverished.

His wish to be left alone granted, he has crafted a life that is, humanly speaking, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and in terms of the time he managed to spend truly living, pathetically short. To really live, it is not enough to rely on bureaucracies to care for others – one must roll up one’s sleeves, extend one’s own hand, and open one’s own heart. When Scrooge awakes Christmas morning and realizes that the ghosts did their work in a single night, he is overjoyed, and sets about putting his resources to work enriching the lives of others. Generosity makes possible a happiness he had never known.

In his day, William Thackeray was perhaps Dickens’ greatest literary rival and had reason to rue the enormous success of “A Christmas Carol.” Yet, he said, “Who can listen to objections regarding a book such as this? It seems to me a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it a personal kindness.” The key word here is personal. Dickens performs a kindness by reminding us that true generosity must be personal. Social welfare programs notwithstanding, we can only truly act generously when we do it ourselves, freely and with goodwill.

So long as Scrooge pays his taxes to support the debtors’ prisons and workhouses, he is merely transferring wealth under threat of punishment. He is not giving freely, and he is operating with a very blunt instrument that prevents him from tailoring his gifts to the distinctive needs of individuals and families. Once he begins to give of his own free will, however, he derives real joy from it, and he targets much of his largesse to people he knows well, such as the Cratchit family. Moved by the plight of Tiny Tim, he is philanthropically inspired and activated in a way he has never known.

In other words, it is the spirit that matters – in the case of “A Christmas Carol,” the spirit of Christmas. And while Dickens’ tale and the spirt of the season serve as touching reminders of the vitality generosity can bring, there is no reason that we should not enjoy its bounty throughout the year. The transformed Scrooge enriches many lives, but no life is more transformed and enriched than his own. As Bob Payton might say, it is a transfiguration possible for each of us, if only our minds and hearts are opened to the spirit of giving.