The Threat of Free Speech, Yesterday and Today

History can shine light even in the unlikeliest of places. What may appear to be the most modern and contemporary of problems may turn out to be a mere echo of the past. Fake news, disinformation, and social media may seem to pose strikingly new challenges for free speech—but despite the novelty of today’s innovative forms of online communication, the issues are very far from new. Three hundred years ago, in the early eighteenth century, one of the greatest writers of English was worrying away at the implications of legal and technological change for what were then the emergent values of free speech. That writer was Jonathan Swift.

Swift came of age as the English finally did away with the prior restraints that had inhibited and curtailed the press since its invention in the late Middle Ages. Famously, the Licensing Act was allowed to lapse in England in 1695 (the year in which Swift was ordained as a priest in the Anglican church). For the first time, the press was uncensored. This did not mean that writers were suddenly free to print whatever they pleased. Work that was hostile to the authorities or critical of the government would attract the attention of criminal law, with prosecutors being quick to charge writers, printers, and publishers alike with the offence of seditious libel. Those convicted would be sentenced to stand in the pillory. Swift, despite his brilliantly biting satire, managed somehow to avoid this fate, even if a number of his near contemporaries were not so fortunate. Daniel Defoe, for example, was pilloried.

Actions for seditious libel, however, were taken in the courts after the event—after the offending material had already been published. From 1695 on, the press did not have to seek anyone’s permission—anyone’s licence—before it went to print. David Hume was far from alone in celebrating this advance as if it meant Great Britain was the freest country in Europe: “Nothing is more apt to surprise a foreigner,” he boasted, “than the extreme liberty, which we enjoy in this country, of communicating whatever we please to the public.”

Writing in a similar vein in the 1760s, the great English jurist Sir William Blackstone, in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, opined that:

The liberty of the press is … essential to the nature of a free state, but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press. But if he publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.

Blackstone continued as follows:

to punish (as the law does at present) any dangerous or offensive writings, which, when published, shall on a fair and impartial trial be adjudged of a pernicious tendency, is necessary for the preservation of peace and good order, of government and religion, the only solid foundations of civil liberty. Thus the will of individuals is still left free; the abuse only of that free will is the object of legal punishment.

If that is what passed for freedom of speech in the eighteenth century, our standards today are more exacting. Under the First Amendment to the US Constitution, for example, Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech. Only the narrowest range of exceptions is permitted. Speech so violent it amounts to “fighting words,” speech that is obscene, or speech that is defamatory may be silenced, but the US Supreme Court has worked hard since at least the 1960s to ensure that these exceptions are drawn as tightly as possible.

Not so for Blackstone. In his conclusions on the topic, Blackstone quotes approvingly an unnamed “fine writer on this subject,” who says that “a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not publicly to vend them as cordials.” That is, even if in the 1760s the law no longer worried all that much about what men thought (within the privacy of their minds), once they started making their views known to the public, they had better be sure that what they were saying was wholesome and not noxious. Blackstone does not identify who his “fine writer” was. But it is Jonathan Swift—the quotation is from Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

Two of Swift’s earlier works, The Battle of the Books and A Tale of the Tub, published together in 1704 but written in the mid-1690s, gave voice to concerns about the implications for free speech which were to stay with him for much of his career, including in his masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels. The Battle of the Books is ostensibly a fable about the ancients and the moderns. A Tale of the Tub is a complex piece of literary, political, and religious satire, more or less impossible to categorise but which, in the main, may be read as an allegorical parable about the development of Christianity in Europe. Both pieces contain a range of prefaces, introductions, letters dedicatory, and digressions, in which Swift takes aim at the proliferation of “Grub Street” scribblers whose inferior works, after the lapsing of the Licensing Act, were pouring in his view all too freely from the London presses.

In The Battle of the Books, he writes that:

ink is the great missive weapon in all battles of the learned, which, conveyed through a sort of engine called a quill, infinite numbers of these are darted at the enemy by the valiant on each side, with equal skill and violence, as if it were an engagement of porcupines.

He imagines a character, representing Criticism, with her parents Ignorance and Pride sitting on either side of her. Alongside them is her sister Opinion, “light of foot, hoodwinked, and headstrong, yet giddy and perpetually turning.” In front of them play her children, Noise and Impudence, Dullness and Vanity, Pedantry and Ill-Manners. Criticism explains that:

Tis I who give wisdom to infants and idiots; by me, children grow wiser than their parents; by me, beaux become politicians, and schoolboys judges of philosophy; by me, sophisters debate and conclude upon the depths of knowledge; and coffeehouse wits, instinct by me, can correct an author’s style and display his minutest errors without understanding a syllable of his matter or his language.

In an unlicensed age, any fool can be a critic. Anyone can pick up a pen. Everyone has an opinion, no matter how hoodwinked or headstrong. And, to cap it all, everyone has a megaphone.

The humour of Swift’s style should not obscure the seriousness of his point. He was appalled by what he read. As one commentator has put it, the end of licensing had created a “cultural swamp” in which “imaginations did not so much soar as sink” and where prose lacked all form, “like bilge.” The same is said now not of Grub Street but of social media. Twitter and its ilk are a swamp, in which bilge drowns out truth, and where the noise is both endless and endlessly misleading. Falsehood speeds around the globe while the truth is still tying up its bootstraps.

Swift had a deeper point. For it was not just the “literary mediocrity” of Grub Street that irritated him: it was also that the new fashion for free speech was based on a profound error and that its consequences were likely to be highly dangerous. The error, in Swift’s view, was to imagine that what went for freedom of conscience should go likewise for freedom of speech.

If we want free speech, we will just have to put up with its vices, its drawbacks and its inconveniences, fake news and disinformation included.

Swift, as we have noted, was an Anglican—a theologian, an ordained priest, and, for thirty years, Dean of St Patrick’s in Dublin. He understood conscience to mean the “liberty of knowing our own thoughts,” a liberty ”no one can take from us.” Conscience, as such, was wholly internal—it “properly signifies that knowledge which a man hath within himself of his own thoughts.” Swift was opposed entirely to the ”quite different” meaning which, in his day, conscience had come to acquire:

Liberty of Conscience is nowadays not only understood to be the liberty of believing what men please, but also of endeavouring to propagate the belief as much as they can and to overthrow the faith which the laws have already established, to be rewarded by the public for those wicked endeavours.

This, he said, was the view of “fanatics” who, moreover, show not the slightest ”public spirit or tenderness” to those who disagree with them.

The expansion of liberty of conscience into freedom of speech was not only an error for Swift: it was perilous. In particular, it was hazardous to public order and the established authority of church and state. This was the danger Swift alluded to in his preface to A Tale of the Tub, where he refers to “the wits of the present age being so very numerous and penetrating, it seems the grandees of Church and State begin to fall under horrible apprehensions.” Swift was aghast that the slightest murmur against a minister of the Crown could lead directly to the pillory, whereas displaying “your utmost rhetoric against mankind,” telling them “we are all gone astray,” was regarded as the benign delivery of ”precious and useful truths” no matter how destabilising it was to peace, order, and good government.

If these views were Tory in character, it did not follow that Swift thought the state could or should return to the old ways of suppression. Swift knew which way the tide was flowing and he was more than astute enough to realise that any official attempt to obstruct it would be futile. When he urged his friend, the editor of the Tatler magazine “to make use of your authority as Censor, and by an annual index expurgatorius expunge all words and phrases that are offensive to good sense, and condemn those barbarous mutilations of vowels and syllables,” he knew full well it was never going to happen.

The genie was out of the bottle, and there was no putting it back. The power of the genie—the power of free speech—may be liberating. But it could also wreak havoc, bringing with it its handmaidens: criticism, ignorance, pride, and, worst of all, ill-formed opinion. Freedom had come at a price, and Swift spent many a long year wondering whether it had been a price worth paying. In Book II of Gulliver’s Travels, Swift has the King of Brobdingnag tell Gulliver that:

he knew no reason, why those who entertain opinions prejudicial to the public, should be obliged to change, or should not be obliged to conceal them. And, as it was tyranny in any government to require the first, so it was weakness not to enforce the second.

This is why “a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not to vend them about as cordials.”

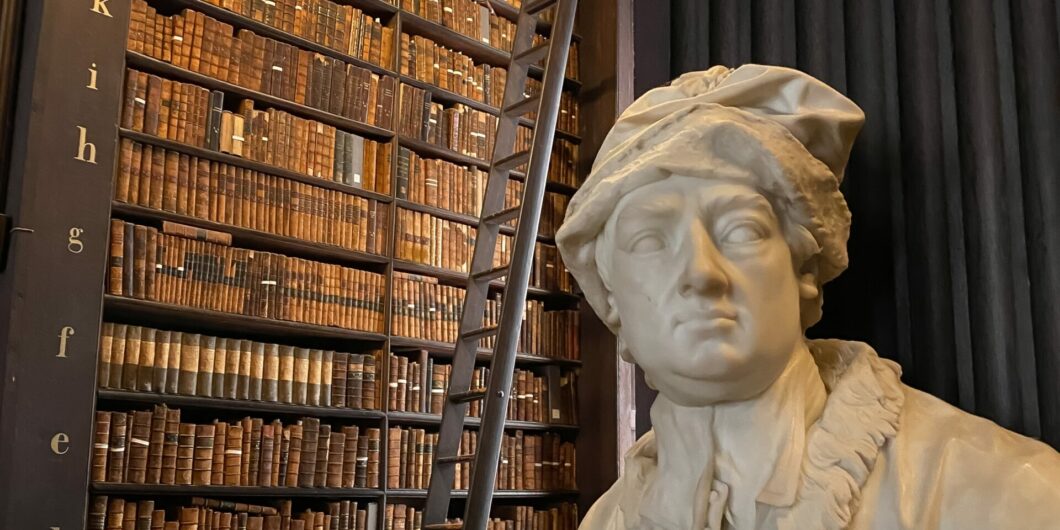

Swift was far from alone in his time in thinking this out loud. We have seen that he had Sir William Blackstone for company. Likewise, he had Samuel Johnson. Consider what Dr Johnson has to say, for example, in his Lives of the Poets (1779), about Milton’s great seventeenth-century tract against censorship, Areopagitica:

The danger of such unbounded liberty, and the danger of bounding it, have produced a problem in the science of Government, which human understanding seems hitherto unable to solve. If nothing may be published but what civil authority shall have previously approved, power must always be the standard of truth; if every dreamer of innovations may propagate his projects, there can be no settlement; if every murmurer at government may diffuse discontent, there can be no peace; and if every sceptic in theology may teach his follies, there can be no religion. The remedy against these evils is to punish the authors; for it is yet allowed that every society may punish, though not prevent, the publication of opinions, which that society shall think pernicious; but this punishment, though it may crush the author, promotes the book; and it seems not more reasonable to leave the right of printing unrestrained, because writers may be afterwards censured, than it would be to sleep with doors unbolted, because by our laws we can hang a thief.

Johnson is clear in this passage—as he was elsewhere in his work—that, if we are a society that seeks truth, we cannot have pre-publication state censorship, for censorship collapses truth into power. But, at the same time, the absence of licensing causes harms of its own—harms to settled authority, harms to public order, and harms to religious authority, too. Hence the need to retain causes of legal action that can be taken against authors whose work is seditious. And yet, as Johnson surmises, this does not always work. For one thing, going after a book that is seditious may serve only to amplify that book’s ability to broadcast its message and, for another, it is no more logical than encouraging a burglar to steal your possessions knowing that you can take legal action against him after he has done so. For Johnson, these appear to be problems of good governance that admit of no solution. If we want free speech, we will just have to put up with its vices, its drawbacks, and its inconveniences, fake news and disinformation included.

That is not a new conclusion, even as the technologies of communication evolve. On the contrary, clear-sighted thinkers have understood it ever since it was first set out by Jonathan Swift.