Trading Constitutionalism for Bureaucracy

In eras of unrest, the scope of politics changes, as subjects once considered outside power’s scope get drawn into contests over who holds it. A subtle but significant example of this shift surfaced two months ago in The New York Times, in an opinion article that politicized history without acknowledging that the historical lens it used was far from definitive. The article, titled “America is an Empire in Decline. That Doesn’t Mean it Has to Fall” by political economist John Rapley, used an interpretation of the Roman Empire’s dissolution to endorse policies favored by the Washington establishment.

As Rapley describes it, Rome’s history with the barbarians who eventually conquered it matches America’s 75-year relationship with countries like China, which have used “growing markets and abundant supplies of labor” to begin to exert political force. But, Rapley argues, unlike Rome, America has an “out” provided by the free market. “Western countries … still retain an edge in knowledge-intensive industries” and “will require workers,” which means that “migration … [is] what stands between the West and absolute economic decline,” as long as we avoid “an unnecessary, [wealth-draining] conflict” with China. In Rapley’s concluding recommendations, Americans should “give up trying to restore [our] past glory through a go-it-alone, America First approach” and work with China on “pressing dangers … such as disease and climate change” while maintaining our global position through our currency, our capital, our military, “the soft power wielded by [our] universities,” “the vast appeal of [our] culture,” and alliances with “a coalition of the like-minded.”

Rapley’s piece supports the social, economic, and foreign policy favored by the Democrats and centrist Republicans who have largely, though not exclusively, guided Washington policymaking for the past 75 years. But its use of Roman history makes it a sharper version of a more recent political trend on the rise since at least the early 2000s: political prognosticators reading America through an interpretation of Rome favored by prominent scholars like Peter Heather, who argue that Rome’s fall came at the hands of foreign barbarians forming powerful new confederations, entering the empire’s domain, and then combining into larger groups the empire could not defeat. In the view of these analysts, Rome’s lessons for America involve harnessing our national government to prevent this fate of outside takeover from present-day threats ranging from Islamists to the Chinese—whether by addressing a “chronic manpower deficit” in our army, attending to national physical health, encouraging migration to boost the workforce, or projecting “soft power” abroad.

But recently, a more subversive academic interpretation of Rome’s fall has developed which justifies a very different politics in America: that of constitutionalists, de-centralizers, and believers in reducing the power of the national state. According to academics who adopt an alternative interpretation, the Roman Empire’s decline came not from the outside but from within. In fact, the story of barbarian takeover was a fiction invented by the very people who really destroyed Rome: imperial bureaucrats who concentrated power under the false justification of protecting the empire from “barbarians,” which in practice was a political label deployed against dissenters. This is a historical story that both rewrites major aspects of Roman history and has serious implications for America today.

Rome’s Fall Came from Bureaucracy’s Rise

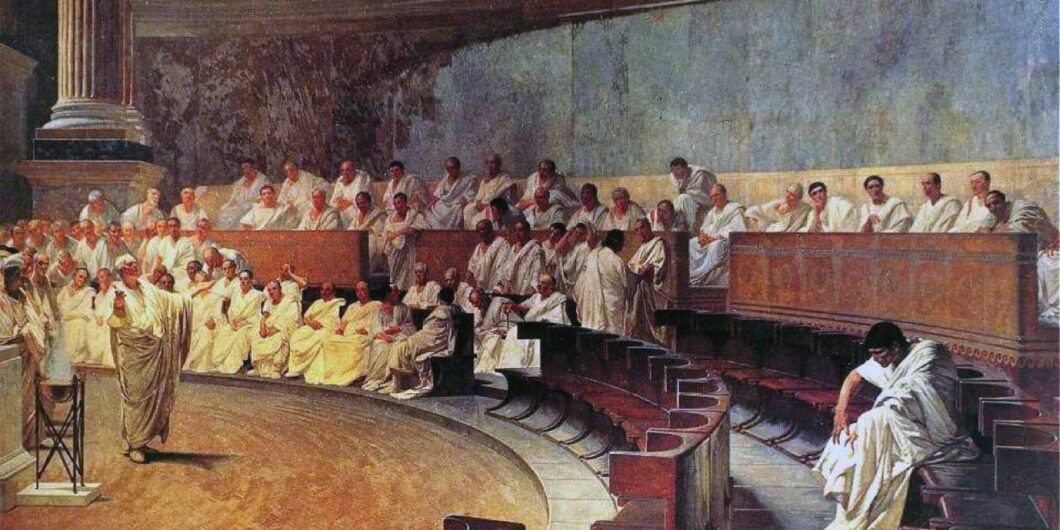

The most prominent contemporary thinker who has articulated this thesis may be the historian Michael Kulikowski, the author of The Tragedy of Empire who holds that, in the words of the proverb, “the fish rots from the head downward.” Kulikowski’s general thesis isn’t new: older historians have traced decisive changes in Rome to the shift to imperial government under Augustus, as Roman assemblies which had shared power with a senatorial elite were reduced to breads-and-circuses and the Senate to an organ of the emperor’s control. But Kulikowski extends his examination by several centuries to focus on Roman government after 200 CE and the way it led to the Western Roman Empire’s fast dissolution after 395 CE In the process, he uncovers surprising facts about the effects of the imperial state created by Augustus’s successors. According to him, the roots of the empire’s decline truly began with a new class of elites: “equestrians” or “administrators,” experts or specialists brought in by emperors, who exercised a silent revolution against the old senatorial class. These bureaucrats were committed to standardizing and centralizing government which in the past had operated off regional customs and concerns, and their commitment to “impersonal” administration was matched by new opportunities to ply their trade.

The biggest of these opportunities came from Emperor Caracalla’s “megalomaniac gesture” in 212 CE of granting full Roman citizenship to almost everyone in the empire. This shift meant that the new equestrians had to work out how diverse populations—now considered citizens—would relate to each other under Roman law. And this, in turn, meant aspiring to a level of governing “uniformity”—government as standardized “managerial” practice instead of a product of regional customs—that had never been “possible” or “necessary.” How would the multiplying equestrians and their emperors explain this new intrusiveness, this conviction that “uniformity can be achieved and therefore should be achieved,” over populations that had been left alone? With rhetoric, as language that until recently scholars had considered “imprecise bluster” began to suffuse Roman laws.

This new language involved a “binary that brook[ed] no compromise” between two categories: those on the right side of whatever uniform project the government embarked on, true civilized Romans, and those who resisted it, uncivilized barbarians. Crucially, the term “barbarian” did not refer to an actual, stable category of people. Instead, it was a mutable definition that could apply to groups regardless of geography (whether they lived inside or outside the empire) or ethnicity. At its root, it was deliberately “polarizing rhetoric” in which opponents of government policy and law were, by definition, barbaric, uncivilized, and anti-Roman “in their very being”: “necessarily excluded from the Roman polity and the protection [it] offer[ed].”

The force of this rhetoric was precisely that it could apply to anyone, depending on the emperor’s desire. Originally, it helped justify persecuting Christians. Then, when Emperor Constantine reversed course, pagans became the outsider barbarians while Christians became civilized Romans. These moves multiplied as different factions backed by provincial elites contested for power over the empire: competitions with enormous stakes given Rome’s newly centralized reality. The weaker these competitors were, the more they used rhetoric to justify their moves and label their opponents. In the end, the bureaucrats became the servants of these power players and the rhetoric they themselves had helped create: if the “[equestrian] aspiration to uniformity of governance is where we find the ideological shift to … totalizing discourses” then the later persecutions became examples of “an equestrian managerial attitude working on behalf of [the] new totalizing … discourse,” e.g. bureaucracy serving totalitarian ends.

Eventually, a Germanic transplant named Alaric, resentful at being denied advancement by bureaucratic operators who for various reasons wouldn’t allow it to him, embraced the label of barbarian and the uncivilized destructiveness it implied, threatening to sack and then actually sacking Rome. In the process, he put to rest the fiction that the empire had become anything other than warring groups fighting for control of a state that they had weakened with their efforts. As Kulikowski puts it, “[the] people ripping down elements of the state structure in order to control it … [found] that [they] hollowed everything out, there [was] nothing left, and it [fell] apart.“ But later historians of Rome’s decline ignored these realities, using equestrian sources for evidence and accepting these sources’ barbarian-Roman dichotomy at face value. The result is that, up to today, historians continue to portray the fall of Rome as a product of “foreign” invaders from beyond its borders who crossed over, rather than what it really was: the result of “Romanized” actors like Alaric taking over a state which equestrian centralization and its effects had already largely destroyed.

Like mid-twentieth-century America, Rome changed when a new class of institutionalists began supplanting legislatures with bureaucracies and concealing the shift with idealized rhetoric.

America’s Centralization Began with Bureaucrats

Though Kulikowski draws only a few contemporary parallels to his view of Rome’s decline and wouldn’t necessarily share a constitutionalist’s approach to American history, his narrative of Rome maps with startling precision onto America’s since 1945. This was when our shift to empire empowered national bureaucrats to execute a silent revolution against state legislatures, chapter-based associations, and the national Congress which had helped shape politics up to that point. Like the Roman equestrians, the new American bureaucrats justified their move with rhetoric. But their move’s fundamental function was to destroy the balances of the Constitution between the federal and state governments: sucking power from the peripheries (the states) and toward the center (Washington, DC).

The first of these bureaucratic takeovers was judicial, as the Supreme Court asserted that ensuring “equal rights” demanded unprecedented national judicial control over state governments. This control wasn’t only for correcting egregious wrongs like Southern segregation but for handling issues of legislative apportionment, the relationships between churches and states, and states’ employment policies. Even supporters of these rulings acknowledged that some of them had no basis in the Constitution. And, though some were hailed as “pragmatic compromises,” their real significance was that national appointees were making choices they had never needed to make before.

National executives exacerbated these shifts. America’s Caracalla, arguably, was Lyndon Johnson, whose civilizing quest in Vietnam and Great Society programs drove Washington expansion and made bureaucrats arbiters of race relations and state-run programs for Great Society progressive ideals. Johnson’s successor Richard Nixon, another tortured vessel of ambitions, increased regulatory authority at an even faster clip. Thanks to their efforts, Washington became a city of administrators, regulators, and corporate lobbyists who ensured that new bureaucratic regulations fell on small firms not large ones. All the while, Congress, the most representative branch of the national government, became a blank check for executive action, thanks in part to Supreme Court rulings which mixed assertiveness over the states with deference to the Executive.

Like in the Roman Empire, this revolution in affairs was a silent one, because America’s new equestrian class produced its own propagandists, this time from government-funded universities and corporate media. At their hands, rhetoric suffused reporting, and politics was discussed in terms of its moral promises or its problem-solving “pragmatism”—ignoring the fact that both the morality and the pragmatics flowed from a newly-centralizing national government. Indeed, whether the project was crusading Wars on Poverty and Crime, or split-the-difference Supreme Court rulings on issues like affirmative action and abortion, America’s moral and practical agendas now came from Washington, DC. Only in subversive academic circles were these moves discussed in terms of the actual power shift that was occurring. Only in these circles was an important question asked: had a centralized government grown so powerful that it made legal rights into “parchment guarantees” that could be easily taken away?

New Civilizers and New Barbarians

In the meantime, the new equestrian classes of propagandists and bureaucrats mixed, bringing distinct ideological projects that they imposed through the centralizing state. If the first movers of this mix were Kennedy-Johnson Democrats, their most successful immediate successors were the academics, magazine writers, and think tank denizens who formed the neoconservative movement which pushed a war on crime and then a war on terror often using the language of civilization and barbarism to justify putting different groups outside the protection of America’s laws. In an offhand reference, Kulikowski cites the neoconservative rhetoric about terrorism as a military struggle, but he could also hone in on the rhetoric about the Black underclass that prominent neoconservative academics used to justify national enforcement against “superpredators”: purported inner-city barbarians who “are so impulsive, so remorseless, that [they] can kill, rape, maim, without giving it a second thought.”

The next academic-media movers were progressives, who also came from the newly-powerful academic-bureaucratic sectors but whose definitions of heroes and villains differed. At their hands, and with neoconservative support, the identity of “the other” has changed—no longer Black youth or Muslims but “deplorables,” “racists,” and “Christian nationalists.” Still, the totalizing discourse remains the same, one that justifies an ever-escalating series of power grabs. Tellingly, as far back as fifteen years ago, the Bush Administration was taking this approach: it brought “civilization” to Iraq even as it argued for amnesty for undocumented immigrants in totalizing terms—dismissing opponents as bigots and ethnonationalists—and strengthened purportedly “free” trade with China that, when it came to America’s strategic position vis-a-vis China, wasn’t necessarily free. Today, the Biden Administration has doubled down on these moves: allowing unchecked unauthorized migration in the name of “inclusive” ideals and economic growth even as it emphasizes strategic cooperation with China and mounts a war to defend “civilization” against Russia.

Circling back to ancient Rome strengthens the parallels between empires. Like mid-twentieth-century America, Rome changed when a new class of institutionalists began supplanting legislatures with bureaucracies and justifying the shift with idealized rhetoric. Like today’s bureaucratic parlance about “deplorables” and “insurrectionists,” the Roman rhetoric of “barbarians” justified using state power against anyone opposed to new administrative agendas. Like today’s operators, the Romans promoting these agendas used their “new totalizing conformist discourse” to enforce “managerial and ideological uniformity” over parts of life from taxation to religion. Like our own zero-sum politics, competition for power in Rome increased as centralization did, with the result that institutions were hollowed out by factions trying to control them.

These parallels to Rome clarify a likely end of the road for America if we fail to return to our constitutional structure. They also point to the dangers of listening to a media apparatus more interested in using the past for propaganda than in considering histories that might undermine its authority.