Charged with a duty to apprehend offenders, police officers must be prepared to use force. Armed confrontations in these circumstances are inevitable.

We Should Still Love Kojak

NYPD detective Lieutenant Theodopolis “Theo” Kojak’s eponymous CBS series represented something new in police dramas when it debuted fifty years ago this October. It had to—in 1973 there were more than a score of crime‐oriented shows on prime time. What Kojak offered to separate itself from its glamorized competitors was a more gritty, straight-from-the-headlines realism in its sympathetic portrayal of police work. Though only airing for five seasons, it became a global phenomenon, and deserves revisiting today, especially for its understanding of law enforcement, criminality, and even human nature.

The Singular Savalas

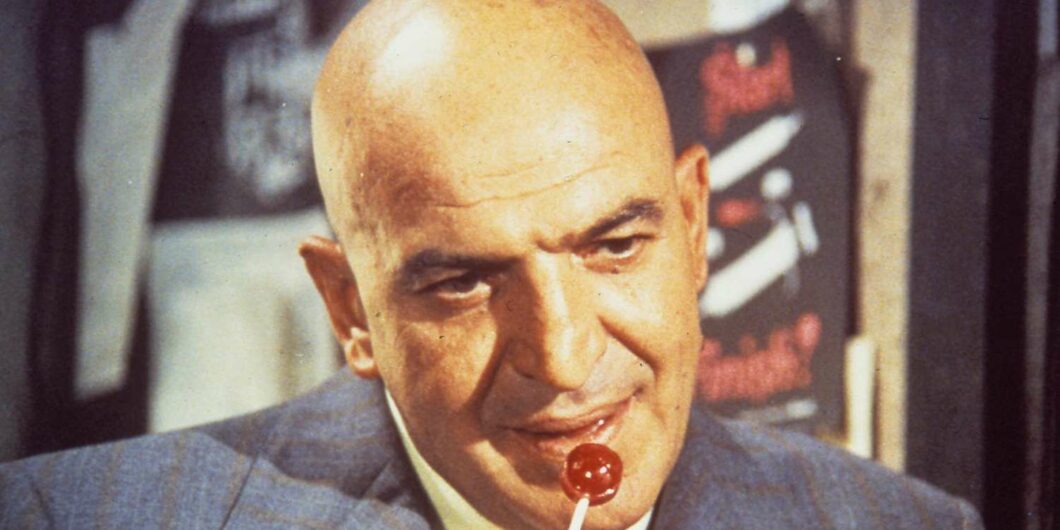

More than anything else, what made “Kojak” was its star, the late Greek-American Aristotelis “Telly” Savalas. It was a bit of a gambit by the show’s creators, as a 1973 New York Times feature explained. Savalas was a “certified movie monster” and “perennial heavy” whose previous screen roles included, perhaps most famously, a religious fanatic and sex deviant in The Dirty Dozen, as well as “a variety of convicts and gangsters, sadistic army sergeants, supercriminals and assorted unlovables ranging from Al Capone to Pontius Pilate.” The imposing six-foot-plus Greek seemed to emanate menace, with his brazenly bald cranium (a then-uncommon purposeful hairstyle), hooked nose, thick neck, and heavy‐lipped mouth.

In that respect, the role of an incorruptible cop with a heart of gold and a well-stocked wardrobe of fashionable suits was a departure for Savalas. But in other ways, the actor—whose upbringing in a Long Island community adjacent to Queens gave the character much-needed street cred—was well-suited as an NYPD detective. Savalas already had the tough-guy image down and soon proved a master of the quick, snarky quip that became ubiquitous in future police dramas. Nor was that persona simply a reflection of his acting abilities. Drafted into the US Army during World War II, he served in a medical training regiment until a car accident put him in a hospital for a year with a broken pelvis and concussion. And, though it mystifies me, Savalas had sex appeal: at one point in the 1960s he was even voted third-sexiest man on screen.

Detective Kojak thus represented a composite of Savalas’ own diverse background: a kid from the streets with savoir-faire, an athletic wit with a penchant for public service (Savalas in his youth was a professional lifeguard; after his military discharge, he attended Columbia and worked for Voice of America). With his characteristic flair, Savalas told the New York Times: “This is an interesting cop, a feel cop from a New York neighborhood. A basically honest character, tough but with feelings—the kind of guy who might kick a hooker in the tail if he had to, but they’d understand each other because maybe they grew up on the same kind of block.”

Kojak’s Oikos

Savalas’s description of Kojak—tough but also avuncular; a virtuous pragmatist who may bend but never breaks the rules—certainly comes across in the series. The detective bounces between playful, witty jabs and truculent barking, regardless of the interlocutor. Criminals, supervisors, uncooperative FBI agents, and even members of his squad (which included his real-life brother George Savalas) are all objects of Kojak’s sharp tongue. But Kojak is unswervingly faithful to his men and the broader NYPD, because, in his mind, the force represents the very people (and family) he has sworn to protect.

In that same New York Times interview, Savalas opines on law enforcement:

I also think it’s incredible that guys—the police—expose themselves to that kind of risk for the peanuts they get paid. And I think we should accentuate the positive as well as the negative. Look around you. I don’t know when in history we’ve been any lower. In our stupidity, we have put the focus on the outhouses of the world. And the people we put on pedestals—Mick Jagger going wild on some stage.

Many episodes depict the threats police officers encounter in the line of duty, sometimes simply because of the uniform they don. And despite the detective’s insuperable style, Kojak’s office is a disheveled, dilapidated disaster, the paint around the door handle conspicuously worn off. The entire precinct bespeaks that same blue-collar, overworked, underpaid ethos.

Nevertheless, “Kojak” does not avoid the controversial, contentious elements of police work. In one episode, he is the recipient of a tongue-lashing from an indignant spouse of a black cop mortally wounded by a drug dealer. “You used him!” the woman screams, demanding Kojak justify her husband’s fate, stemming as it does from his skin color making him an ideal candidate for sting operations with inner-city lowlifes. The detective responds that it’s what her husband wanted, to clean up the streets that they all grew up on. And, he adds with dramatic effect, it’s what she wants too.

Kojak may in one sense be colorblind, but neither is he indifferent to the realities faced by racial minorities and immigrant communities—he is, after all, like Savalas, a proud Greek-American. In an episode pitting established Italian mafia families against a young, aspiring Chinese-American crime syndicate, Kojak makes an impassioned plea to an elderly Chinese shopkeeper with information that could preclude a bloody gang war. The detective, speaking through an NYPD Chinese-American interpreter, acknowledges the cultural distance between him and the woman, as well as his ignorance of Chinese culture, of which he is “ashamed.” He appeals to their shared desire to be understood and appreciated. In Kojak’s America, all cultures are respected and honored, but are also expected to participate in the process of assimilation into a shared American identity, manifested most immediately in the diversity of NYPD.

Presumably, Kojak’s popularity also stemmed from the fact that many Americans agreed with the show’s presumption that America needed a robust police presence to curb crime.

Criminals, alternatively, come in all kinds. Sometimes they are cruel, wicked villains, their souls deeply malformed by years of iniquity, and thus possessing few, if any redeemable qualities. Others are more complicated, torn by a panging conscience or legitimate affections and allegiances to family or loved ones. One episode features a young gang member stricken by regret for involving his sister in his crimes; another a Vietnam veteran manipulated into killing those he (wrongly) thinks are responsible for his wife’s murder.

Yet as diverse as criminals may be—and as empathic as the audience may be to their plight— the series works under the presumption that criminality, regardless of the intentions, is an objective wrong that must be restrained and punished. This is no modern, morally relativist drama where the lines between good and evil, hero and villain are so cleverly (and cynically) blurred as to forfeit all distinctions. In every episode, it is ultimately Kojak, regardless of his personality defects and vices, who remains in the right through his embodiment of law and representation of the greater polis. He is Orwell’s “rough man standing ready” to do violence on behalf of others to preserve the safety and stability of society.

Nevertheless, Kojak also evinces themes aimed at reinforcing the importance of community, family, and faith. After freeing an elderly man held hostage by violent thieves, Kojak takes him out for a cup of coffee. He procures a puppy for the young children of a colleague killed in the line of duty. He makes time for the important events of his extended family and dotes upon a precocious niece. When she’s kidnapped, Kojak finds her parents praying for her safety at their local church.

Kojak’s Continued Relevance

Though the program only lasted five seasons, Kojak was resoundingly popular. TV Guide in 1999 ranked Theo Kojak number 18 on its “50 Greatest TV Characters of All Time” list. Many famous actors made early appearances on the show, including F. Murray Abraham, Danny Aiello, Richard Gere, Harvey Keitel, Sylvester Stallone, John Ritter, and James Woods. In some parts of the Spanish-speaking world, Kojak is a brand of lollipop, because the detective regularly sucked on the candy as a substitute for cigarettes. When a character asks Kojak about his lollipops, the detective, in his usual artful humor, explains: “I’m looking to close the generation gap.” In the 1970s there were Kojak walkie-talkies, burglar alarm systems, trading cards, board games, and action figures.

The show’s legacy is more than simply the brick-a-brack, or the medium that best suited the persona and temperament of the sui generis Savalas (a 2005 reboot with a different cast embarrassingly flopped after one season). As one IMDB reviewer succinctly puts it: “All Cops should be Theo Kojak.” In an America so (sometimes seemingly willfully) confused about right and wrong, heroes and villains, Kojak represents what we truly want from our public servants: unimpeachable integrity, unswerving dedication, and a willingness to sacrifice. If they possess a healthy ironic cynicism regarding the tragedies and paradoxes of their labors, so be it.

Presumably, Kojak’s popularity also stemmed from the fact that many Americans agreed with the show’s presumption that America needed a robust police presence to curb crime. In 1975, for example, political scientist James Q. Wilson published his influential collection of essays, Thinking About Crime, which argued for incapacitation as the most effective explanation for the reduction in crime rate. Yet as the “defund the police” sloganeering of 2019 proved, such sentiments about law enforcement—at least among liberal urbanites—have seriously eroded.

City Journal in its Spring 2023 issue observed that for New York’s Finest, “police spending alone [among other city funding categories] has shrunk.” In 1980, NYPD’s budget was 5.2 percent of the overall city budget; in 2022, policing comprised a 4.9 percent share. “By 2022, the city’s uniformed headcount of 34,825 represented a 13.6 percent drop” from its 2000 peak. The result, unsurprisingly, has been a marked rise in crime. The felony level, as of March 2023, was 49 percent higher than in 2019. City Mayor Eric Adams has addressed this crisis not with higher police budgets and more uniformed personnel, but an unsustainable overtime policy, the residual fruits of the recent “Defund the Police” movement. As Detective Kojak might say with the perfect intonation, “Who loves ya, baby?”