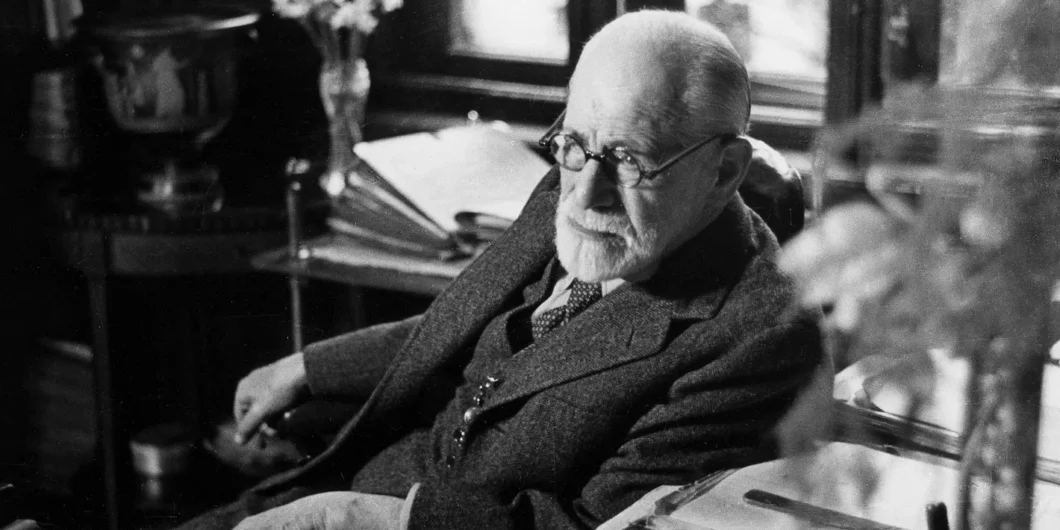

What Was Jewish About Sigmund Freud?

“A man is like a carpenter,” mused Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye, “for a man dies, and so does a carpenter.” Talmud interprets, Adam Kirsch avers, and so did Freud, so Freud is like a Talmudist. In a recent essay entitled “Freud as Talmudist” for the Jewish Review of Books, Kirsch, a poet and critic, equates Freud’s interpretation of dreams with rabbinical interpretation of Jewish law, or Halakhah (literally, “the way”). Kirsch is a secular Jew with a literary interest in Jewish texts. He calls attention to an embarrassing problem. Every so often some ambitious Jewish reprobate goes off the rails and starts his own religion, notably Benedict Spinoza, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud. Because “the Jews” so often are blamed for these antics, Kirsch’s Tevye-esque malapropism deserves a response.

Spinoza, Marx, and Freud were materialists, that is, enemies of religion in general and Judaism in particular. Secular Jews in search of a Jewish sensibility that does not require religious practice invariably find their way to one of this trio. Marx reduced human behavior to economic (class) interests, and Freud reduced it to biological urges, although in his later years, he dabbled in the occult and spiritualism. Except for an enduring source of inspiration for dilettantes, Freud’s influence has faded even more than that of Marx. The American Psychoanalytic Association has just 3,000 members, about 1% of American mental health professionals, of which only 15% are under 50, and 52% are aged 60 to 80. Talmud, by contrast, is studied by perhaps 200,000 yeshiva students every year and hundreds of thousands of Jewish laymen.

Freud as a clinician was a mountebank and charlatan who cured no one, as Frederick Crews recounted vividly in a 2018 book. He was fortunate to retire before the development of medical malpractice law. His reckless experimentation with vulnerable young women left a trail of ruined lives in its wake.

His famous dictum in Studies on Hysteria—“Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming your hysterical misery into common unhappiness”—carried over into his philosophy. People fear castration and so forth, Freud argued, but do not fear death—the starting point of all religion. After the First World War, Freud “discovered” a death drive to parallel the erotic drive that informed all his earlier work. The incongruity of the idea that no one is afraid of death yet inexorably drawn to it didn’t bother him.

One can’t imagine being dead (because to imagine yourself you must still be alive) and therefore can’t fear it, Freud argued. That isn’t quite true; one can imagine oneself rotting and demented, which may explain why the fascination with zombies seems to rise in inverse proportion to religious belief. Adjustment in Freudian terms is the acceptance of the pointlessness and unhappiness of our existence. Woody Allen nailed this in the opening credits of “Antz,” when an ant patient tells an ant psychoanalyst, “I feel so insignificant!” The shrink replies, “That’s a breakthrough. You are insignificant.”

We do not fear our individual death as the death of the culture that allows something of our earthly existence to pass to future generations and thus give purpose to our own brief earthly existence. Consider the extreme case of the last speaker of a dying language, of which there presently are thousands. The cultural artefacts that bear witness to the rapture of love, the euphoria of victory and the anguish of defeat, the ecstasy of divine worship and the grief of mourning, will die with him, and the remnants of the existence of all his antecedents will be erased forever. Of the perhaps 150,000 languages that humanity has spoken in the past few hundred thousand years, that has been the fate of virtually all. Culture is a protest against mortality. It is what makes our lives significant.

Freud’s last book, Moses and Monotheism (1939), portrays Moses as an Egyptian priest who concocted the Jewish religion to lead a rabble of slaves out of Egypt. In Freud’s twisted account, the slaves killed Moses and turned him into a mythical figure out of blood guilt. That supposedly explains both Jewish guilt (at the murder of the national father figure) as well as Jewish pride (at being chosen by Moses).

This tenebrous, penurious, and pessimistic appreciation of the human spirit stems from Freud’s hatred of Judaism. It is anti-Judaism in the strictest sense: Judaism uniquely among major religions specifically commands its adherents to be joyful on specific sacred occasions. Even the prescribed seven-day period, or shiva, of intense mourning after the death of a close family member is truncated if a festival begins. Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, the dominant intellect of the wing of Orthodox Judaism that supports secular studies as an adjunct to Torah, wrote in Out of the Whirlwind,

Notwithstanding the ways in which we have been commanded to fulfill the mitzvah [commandment] of rejoicing on a festival (in Temple times, by eating sacrificial meat; nowadays by other practices such as eating meat and drinking wine), it is plainly clear that this mitzvah in fact entails a joyful heart in the simplest sense, requiring the individual to be joyful on the festival. The specific halakhot [laws] pertain only to how the commandment is to be carried out in a technical sense, but the essence of the commandment, it is clear, pertains to the person’s inner state on the festival. In formulating specific details, the Torah simply directed how the inner joy is to be actively affirmed.

“How do we know, from its method and movement, that Halakhah is optimistic?” Soloveitchik asked. “Simply because the subject matter of Halakhah is of this world and there is very little in Halakhah that deals with any other world. Obviously if they dealt with life in this world so extensively they considered the world worth living in. …The Halakhic subject matter is the human being with all his drives and desires, and Halakah never tells people to stop enjoying life.”

That a great gulf is fixed between Freud’s prescription of “ordinary unhappiness” and the Jewish commandment to be joyful before God is clear enough. But is there a commonality of method? Kirsch cites Susan Handelman’s 1982 assertion that psychoanalysis is “a continuation of the Jewish exegetic tradition.” Rabbinic interpretation, Handelman claimed, assigns “endless multiple meanings” to “each word and letter of the Torah.” That is specious: Rabbinic interpretation does indeed presume that the potential for interpretation of the Torah is boundless as the mind of its Author, but also specifies that there is one right way to do things—one Halakhah—derived from the best interpretation that the outstanding scholars of each generation can derive. Alternative readings may be legitimate—the Talmud exhaustively records minority opinions—but the Halakhah remains with the majority.

Kirsch equates Freud’s fanciful interpretation of dreams with the rabbinic method of deriving legal responsa from Scriptural references:

Freud’s rules of interpretation … treat the simultaneity of events, the resemblance of objects, and the similarity of words in a dream as signifying particular kinds of connection. He also finds meaning in proximity, inversion, and negation. This battery of interpretive rules gives the analyst the power to coax a coherent meaning out of the seeming chaos of the dream. In a dream, Freud writes, “everything is definitely determined, and nothing is left to caprice.”

By the same token, the Jewish sages of antiquity who composed the Talmud are wont “to connect any two verses in the Bible, no matter how unrelated they seem, if they contain the same word, making possible some extraordinary feats of deduction.”

But there is an obvious, enormous difference between Halakhic responsa and dream interpretation which does not occur to Kirsch: Halakhah proceeds from thousands of years of precedents in rulings about marriage, property, ritual cleanliness, Sabbath observance, and every other aspect of Jewish life. New issues arise from time to time, to be sure, for example, the permissibility of in vitro fertilization. These require a hiddush (innovation), but such innovations are grounded in a vast body of earlier decisions, systematically compiled and categorized, and used as reference points for new problems. The edifice of Halakhah bears a close relationship to the process of mathematical proof, which establishes the consistency of new discoveries with previous ones. That was the view of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, the heir to the Brisker rabbinic dynasty that established modern Talmudic study:

Were science to try to penetrate and interpret matter, it would become mythical, but it leaves this to the philosopher. Science does nothing but establish relationships. Science is not interested in the essence of the world but rather in relationships which are expressed functionally by formulae. If the scientist would ever try to investigate electricity as a power he would become a mythologist, but all he does is measure it. The scientist measures light and its results and relationship to others, but he is not interested in finding out what light itself is. Science never explains reality; it merely duplicates it. … The same can be said of the Halakhic method. Halakhic mathematization breaks the concrete act into a number of interdependencies. The totality is atomized and reconstructed piecemeal.

Imagine that a hundred generations of psychiatrists sought to analyze the same limited set of dreams, over and over again, with occasional minor variations. Every new wrinkle of interpretation in each generation, moreover, would have to take into account the work of all the previous generations. If psychoanalysis resembled Talmud study, it would bear no resemblance to Freud’s fanciful on-the-fly speculation.

To Freud, the family is merely the source of neuroses that arise from repression of Oedipal urges. There is no transcendence, only illusions to be exorcised. If that is all there is to life, why inflict it on children?

But Halakhah has no use for dreams, symbols, imagination, and the rest of the stock-in-trade of psychoanalysis. On the contrary, it explicitly rules them out of order. As Soloveitchik told his Yeshiva University students in a 1950 lecture:

Halakhah deals only with realty, plants, death, disease, agronomy, force, classification of species, economic and political life, etc. Its subject matter is completely identifiable with physical and social science. Halakhah never paid attention to dreams or to the decisions of prophets. No person who claims contact with the transcendental can be allowed to solve a Halakhic problem which is a purely human affair. Interference with Halakhah by a prophet is punishable by death. The human mind decides Halakhic problems. The Halakhic experience is logical, rational, and finite.

And Soloveitchik added:

The greatest contribution of Halakhah to Judaism consists in purging Judaism of all mystical, magical and ceremonial elements, while even a civilized religion like Christianity has mythical designs in its practical side. … The mythical character of the Christian services does not demote it to a lower rank or cancel its cultural worth. Halakhic Judaism has eliminated the mythical element and the Jewish performance is deprived of the myth.

In passing, Kirsch cites academic work claiming that Freud was influenced by Kabbalah, without explaining what Kabbalah is or what it might have to do with Freud. We are back to Tevye’s carpenter: Kabbalah is mystical, and Freud is mystical, so Freud is kabbalistic. On the contrary: the mainstream of Kabbalah as formulated by the sixteenth-century sage Isaac Luria and transmitted by mainstream Jewish Orthodoxy is a Biblical philosophy of creation. Readers who want to learn more should look at Joseph Soloveitchik’s lectures on the subject.

As Immanuel Kant showed in his 1781 Critique of Pure Reason, the metaphysics of the Neo-Platonists and the Aristotelians are bedeviled by “antinomies,” or paradoxes that Reason cannot resolve. We cannot prove that the world had or did not have a beginning in time and a limit in space; whether or not all substance can be decomposed into parts; whether or not a deterministic process controls events; or whether there exists a necessary Being. These paradoxes have persisted from Plato’s dialogue “Parmenides” to the problems of modern set theory.

The unmoved mover of Aristotle and Plotinus contemplates himself but does not create. How is it possible for the creator God of the Bible to make a world that was not made of Himself? If God created the world ex nihilo, God was there all along, in which case all of creation is God, as in Spinoza’s pantheism. Luria’s answer, which had enormous influence on subsequent philosophy (especially Hegel), is that God first contracted Himself to make an empty space in which he might then create a world that was not merely an extension of Himself. That contraction, or tzimtzum, is a uniquely Jewish idea, although it bears a distinct resemblance to Hegel’s dialectic. As the late Gershom Scholem explained, the Lurian Kabbalah’s “turbulent God,” the God of creation ex nihilo, contends with the passive, self-contemplating god of the philosophers for primacy in Western thought.

Kirsch mentions Kabbalah only in passing, but he might have found a connection between certain trends in Kabbalah and the mysticism of the German Romantic philosopher F. W. J. Schelling, who also influenced Freud. Prof. Paul Frank of Yale has shown that Schelling’s mystical views resonated with certain nineteenth-century Jewish thinkers. Schelling responded to Kant’s presentation of the antinomies by asserting the existence of “intellectual intuition,” a sort of supra-rational power of mind that resolves contradictions by visionary means. Schelling is an intellectual ancestor of the Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger, whom I characterized as the most destructive intellectual influence of the twentieth century in an essay for Law & Liberty last year. Schelling, Freud, and Heidegger belong to the mystical Romantic miasma that is Western civilization’s greatest threat from within.

Alas, Freud instantiates a Viennese café joke cited by Paul Johnson: “Anti-Semitism was getting nowhere, until the Jews got behind it.” The Jews have no enemies as dire as apostates like Freud, who know just where to insert the stiletto. Freud was dangerous because he was clever. At the conclusion of Moses and Monotheism, published after the 1938 Anschluss drove him from Vienna, he wrote:

We must not forget that all the peoples who now excel in the practice of antisemitism became Christians only in relatively recent times, sometimes forced to it by bloody compulsion. One might say they are all “badly christened”; under the thin veneer of Christianity they have remained what their ancestors were, barbarically polytheistic. They have not yet overcome their grudge against the new religion which was forced on them, and they have projected it on to the source from which Christianity came to them. The fact that the Gospels tell a story which is enacted among Jews, and in truth treats only of Jews, has facilitated such a projection. The hatred for Judaism is at bottom hatred for Christianity, and it is not surprising that in the German National Socialist revolution this close connection of the two monotheistic religions finds such clear expression in the hostile treatment of both.

Freud borrowed this insight from another free-thinking German Jew, the poet Heinrich Heine, who at the end of his life declared that he had returned to the God of his fathers after years of herding swine among the Hegelians.

Freud remained an enemy of Judaism until the end and his legacy remains a liability. “Ordinary unhappiness” is the dilute acid slowly eating away the foundations of Western civilization. The childless Europeans no longer suffer from the hysterical misery that gave us the World Wars of the past century. They simply are too unhappy to bear children or defend their countries, and distract themselves from this unhappiness with hedonistic pursuits. To Freud, the family is merely the source of neuroses that arise from repression of Oedipal urges. There is no transcendence, only illusions to be exorcised. If that is all there is to life, why inflict it on children?