Perhaps, despite itself, the logic of “defund the police” can point American society in the right direction, toward a renewed spirit of association.

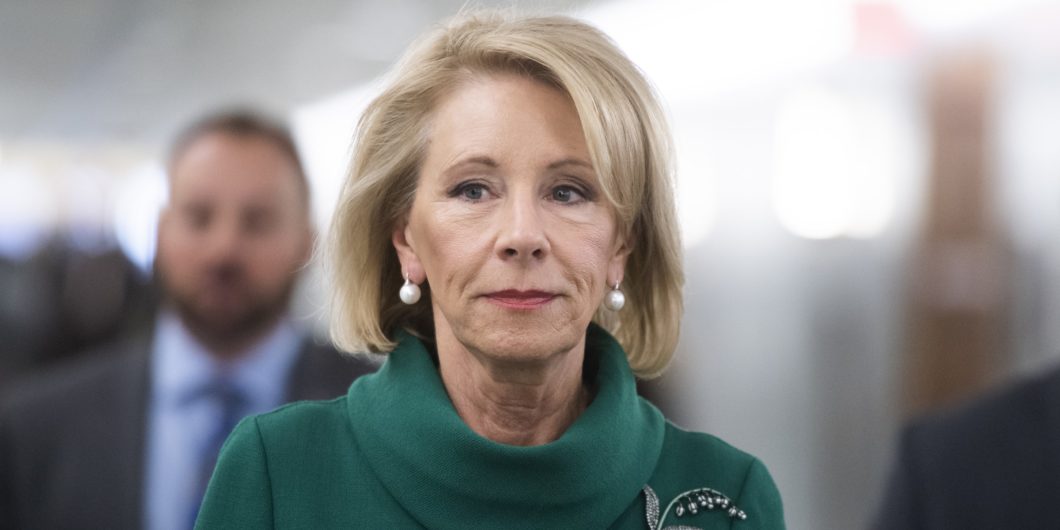

Why Universities Need the New Title IX Rules

Earlier this month, Betsy DeVos, President Trump’s education secretary, announced new Title IX regulations for sexual misconduct by college students. As has been widely reported, while they take allegations of sexual misconduct seriously, they strengthen protections for the accused, permitting cross-examinations by representatives of the parties to disputed conduct and preventing the same college administrator from being both investigator and decision maker. The rules also try to prevent comments about what should constitute misconduct from being used as a predicate for a Title IX claim.

If there were any doubt that the regulations were needed, representatives of universities and colleges, like Ted Mitchell of the American Council of Education, dispelled them by their denunciations of the rules.

The first complaint is that the rules are costly, particularly at the time of the Covid-19 crisis. But these same organizations did not complain of the huge costs imposed by the Obama administration when its so-called Dear Colleague letter forced colleges to ramp up sexual harassment investigations by hiring many more Title IX officials. And they were then under the threat of losing all federal funding, a threat which the new regulations relax (a point Mr. Mitchell chose not to acknowledge).

The American Council also complains that the new Title IX regulations intrude on the management of the university—as if the problem is with these particular regulations rather than the decision to expand Title IX in the first place, a decision taken, of course, by the Obama administration. It further complains that regulations are “legalistic,”—as if a process that may brand a young student for life as a sexual miscreant or predator should not be bound by strict rules. Unacknowledged as well are the many court cases (legalistic no doubt!) that overturned decisions of colleges made under the previous rules, which flouted due process.

We might consider who runs the American Council of Education. Its president, Ted Mitchell, was none other than the undersecretary of education during the Obama administration. That administration gave a green light to the kind of “progressive” policies the administrators that Mitchell now represents would like to implement. The higher-education policies of Democratic administrations are driven by the same constituency groups to which university administrators pay attention.

Thus, it was not surprising that many universities took the Obama administration’s guidance on Title IX rules and made them even worse than they were required to be. My alma mater Harvard was an egregious case in point. Nineteen of its own law faculty described its rules as characterized by “the lack of opportunities for the accused to see the facts against him or her, face the accusing party, and have counsel available.”

Or take Northwestern University, the institution at which I teach. Laura Kipnis, a professor in the Communications Department, was twice investigated, not for any actions she took, but for her principled comments complaining about the injustice of the University’s rules and procedures on matters relating to sexual relations. The cases against her were ultimately dismissed, but not before she was forced to defend herself in lengthy processes, and free speech at the university was chilled.

University presidents are unlikely to be a match for either the ideological fervor of student movements like MeToo or the bureaucratic interests of the lower-level administrators charged with Title IX programs.

Without the kind of clear standards that the new Title IX regulations provide, university bureaucrats will naturally produce unfair procedures that will result in injustice. First, these bureaucrats are almost entirely ideologically on the left—often the far left—and enamored of identity politics. As Sam Abrams of Sarah Lawrence College showed, college administrators are even farther to the left than the faculty, and they seem to shape the views of students in an illiberal direction. (As a reward for Abrams’ op-ed, students attempted to get Sarah Lawrence to revoke his tenure).

Beyond their personal views, even well-meaning administrators have bureaucratic incentives to expand their jurisdiction and increase their discretion. They then become more powerful and less accountable.

And administrators will not often be reined in by either the faculty or the leadership of the university. Some of the faculty are themselves caught up in the social justice wars and are happy with an unfair process so long as it is ideologically sound. Others just stick to their knitting. There are no rewards and some penalties for attacking your administration. Academics have generally remained as courageous as they proved when Allan Bloom wrote in The Closing of the American Mind that at Cornell, where he taught, professors in the natural sciences supported affirmative action because those admitted under lower standards would not take any of their classes.

To be sure, there are occasional exceptions, like the Harvard Law school faculty who opposed their university’s rules on Title IX. But that is indeed exceptional: law professors are professionally interested in due process, and Harvard law professors have so many outside options that they can afford to speak out.

Leaders of universities—Presidents, Provosts, and Deans—are also not likely to control their bureaucracy on issues like Title IX, even if they are not themselves enthusiasts of the causes that motivate their students and subordinates. The modern university leader wants peace on campus above all. Peace makes for an easier life. It is also essential to an administrator’s career, and most senior administrators aim to ascend the ranks of prestige and pay.

Ever since Nathan Pusey’s tenure at Harvard was cut short by his decision to summon the police to throw out the student occupiers of his office, universities’ heads have lived in fear of radical takeovers and have acted to appease their demands. Hence, they are unlikely to be a match for either the ideological fervor of student movements like MeToo, which call for automatically believing all accusers, or the bureaucratic interests of the lower-level administrators charged with the programs.

Thus, the Trump’s administration’s rules are needed in no small measure because they create barriers against the predictable pressures of students, the enthusiasm of Title IX bureaucrats, and the pusillanimity of senior campus officials. They offer a model for how to proceed in drafting any federal regulations applied to universities.

It is true that, in a perfect world, these guidelines would be the second-best. The first-best world would have no such regulations at all, but leave universities to police themselves, disciplined by the common law rules of tort and contract as well as the criminal law. That regime would allow for a diversity of approaches that suit the diversity of institutions. But so long as the government is going to enforce Title IX, only clear and reticulated rules will protect due process and free speech against a university culture that sacrifices them to the madness of young crowds and the fervor of petty bureaucrats.