Can Our Constitutional Order be Revived?

Yuval Levin’s American Covenant depicts the lost world of American political order—and how we might recover it. Nearly all Americans lack a living memory of when the country had a functioning politics and a decent enough culture, so Levin’s elegy is a welcome way of showing Americans that things could be different. Precisely how to bring back something nearly as well functioning is not so clear.

Every political community is an aggregation of different interests and visions of justice and the good where citizens nonetheless share enough to set themselves apart from other peoples of the world. For Levin, Americans “have not only lost sight of the importance of pursuing greater unity,” but also have “tended to forget what unity in our free and dynamic society really involves.” Disagreement is not necessarily the problem. Americans need to disagree better, “more constructively and with an eye to how different priorities and goals can be accommodated.” We need “a way to live with the reality of our diversity and divisions, aiming to mitigate their downsides without harboring the utopian illusion of eliminating them.”

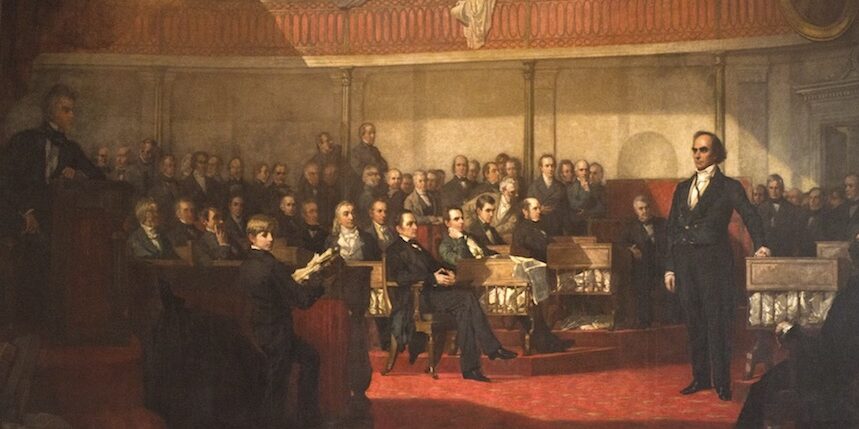

Successive chapters of American Covenant catalog how constitutional politics used to bind the country together amidst diversity of interests and views. The old federalism limited the national government to issues related to the general welfare and a strict idea that states have separate, independent spheres of sovereignty. Diversity within states and unity on general interests. Congress operated through coalition-building and committees, where deliberation and mutual accommodation reconciled representatives to workable laws. Presidents stood for stability in administration and secured public confidence with the non-partisan implementation of laws. Courts kept the system true to itself, policing boundaries between national and state governments, preventing Congress from delegating away its powers to the bureaucracy, and requiring that presidential action had a sound basis in clearly-drawn laws.

America’s unified, if unharmonious culture existed downstream from such constitutional politics. An ethos of competition prevailed. States and also branches of governments competed with one another to serve citizens best. States competed with one another to attract businesses and honorable residents. Competing branches exposed and prevented corruption and abuses of power in other branches. States competed with the national government to serve citizens. Our bicameral, representative legislature compelled negotiation whereby elected officials came to understand one another through give and take, even if they didn’t ultimately agree on means or ends. Aggregation of interests and the spirit of “and” as opposed to “either-or” smoothed over even deep disagreements. Think of the tariff disputes of the 1830s, where conflict fostered a temporary modus vivendi.

As a result, the public managed majority rule while respecting minority rights and viewpoints. National politics required agreement on the relatively few issues affecting general welfare. On issues of local importance, Alabama could do what it wanted, and so could Vermont and Wisconsin. Citizens were engaged in public affairs and felt responsible for their own localities. At the national level, the need for complex majorities reconciled citizens and elites to one another. Law-making took divergent views into account. Deliberation was a norm. Civic education, understood as the practical living out of republican reality, was in the American DNA. What once existed could exist again. Like Levin, I would sacrifice no little blood and treasure to bring back this constitutional order for my children and grandchildren.

This constitutional order has been mostly dead for a while. As Levin shows, the national government consolidates power, states are increasingly administrative units for national ambitions, Congress irresponsibly passes vague laws, legislative leadership centralized decision-making, executives are agents of instability and demagoguery, and courts invent new rights and employ outcome-based reasoning. Gone are the days of “cross-partisan bargaining and accommodation.” The days of zero-sum, “bitter partisanship” are here.

Division runs deep. Partisans within America wish that the partisans of the other side would disappear, either through squelching their freedoms or through fantasies of elimination. For Levin, a politics of mutual annihilation (metaphorically speaking) is “genuinely terrifying.” So both sides of our political divide now reject mutual accommodation and forbearance. Marriages between Democrats and Republicans are extremely rare and neighborhoods are increasingly segregated by politics. Where is this leading? The “only real alternative to a politics of bargaining and accommodation in a vast and diverse society,” Levin writes, “is a politics of violent hostility.” Terrifying, if true.

The “diversity within unity” framework is essential to reconciling America’s factions. Few can imagine what “diversity within unity” would look like in today’s America.

Establishing a more robust federalism will involve confrontation, defiance, and violating established norms.

Perhaps abortion models what a new diversity within unity can be achieved. The Supreme Court played its old constitutional role of policing the boundaries of political power when it returned abortion to the states in Dobbs. States embrace a variety of abortion policies, while Congress mostly sees it as a state issue. Federal solutions turn down the heat of national debates. Federalism works! On the other hand, however, the chief executive and his minions ramped up the lawfare against states and pro-life advocates to undermine Dobbs. Progressives, if they earn more Supreme Court appointments through more electoral victories, will return the country to the Roe framework in a heartbeat. What appears as a model might just end up illustrating how the Left plays for keeps.

It is almost a stop-the-presses event when Yuval Levin imagines significant revisions in our civil rights regime along lines set up in Dobbs. Civil rights laws may have been necessary at one time but now, Levin writes, they have come to represent “an expansive rejection of the logic of federalism” and, indeed, “an alternative to the entire logic of American constitutionalism.” Against the Left’s radical civil rights project, Levin imagines a more radical federalism where conservative reformers “look to disentangle state and federal governance as far as they practically can.” For any of this to work, the Left would have to scale back its ambitions and drop the use of many of its rhetorical tools. Such surrendering is difficult to imagine. Nothing but state-supported perhaps violent hostility from the Left would follow from attempts to roll back civil rights laws even mildly. Cities would burn, again. Activists would squeal. The FBI would arrest anti-civil rights advocates, again. New York’s Attorney General and other colleagues would spring into action, again.

Levin mostly whistles past progressive ideology as well-intentioned and, in any event, “not crazy,” but he also recognizes that it has “been profoundly unhealthy for our fractured republic.” This diagnosis nods toward the late Angelo Codevilla’s cold civil war thesis. The progressive constitution undermines republicanism and an arrogant and unmovable (but well-meaning!) ruling class with a loyal band of clients leads both within and outside of government. For Codevilla, there are other options besides old constitutionalism and violent hostility. There is tyranny too. And tyranny must, if it exists, be resisted. Pursuing a more radical, state-centered federalism is a worthy goal for American constitutionalists today. It would also be greeted as an act of resistance against our current ruling class.

Not calling it tyranny, Levin does not counsel resistance. He wants norms. So dire and terrifying is violent hostility that both sides should, in some sense, be frightened into the old constitutional politics aiming at mutual accommodation. Since the Left is mostly beyond repair, constitutional recovery depends on the Right to embrace constitutionalism once again. Donald Trump’s populism and demagoguery must be rejected. The populist contempt for institutions must be overcome. It is time to build! Conservatives must breathe life into the sub-constitutional mores like regular order and committee systems, embrace presidential humility, and appreciate judicial restraint to make the Constitution great again. Then they will have to practice and model bargaining and mutual accommodation with progressive ideologues who control most of the institutions and have a theoretical and practical distaste for such bargaining and mutual accommodation. Conservatives have been clinging to similar aspirations for the last sixty years or so—and, at this point, the agenda Levin, mostly, would have conservatives get behind looks more like surrender to an imperial power than a viable political platform to restore a viable constitutional order.

The Left has not practiced a “politics of violent hostility,” because it has been able to use its control of institutions to implement hostility without violence. Readers of Law & Liberty are familiar with lawfare, undermining the equal protection of the laws, de-platforming, cancel culture, callousness toward the problems of the white working class, corruption of our election system, and other elements. The progressive establishment is hostile to deplorables who cling to guns and religion. Hoping for “unity amidst diversity” hardly seems sufficient in such a revolutionary situation.

Yet Levin’s embrace of a more radical federalism (though he does not call it that) will be part of any successful attempt to staunch this budding tyranny. Establishing a more robust federalism will involve confrontation, defiance, and violating established norms. (Think Texas Gov. Greg Abbot sending migrants to New York City and deciding to enforce national law himself as opening salvos.) Getting to a more radical federalism will not be normal politics. It might look more like the nullification crisis. It will be icky. It means that the Left’s imperial project runs up against something so strong that it stops. I hope self-proclaimed constitutionalists (among whom I count myself one) will tolerate the ugly, passionate politics necessary to bring robust federalism about.