It is disheartening to realize that the academic Left can’t conceive of conservative constitutionalism as reasonable or intellectually defensible.

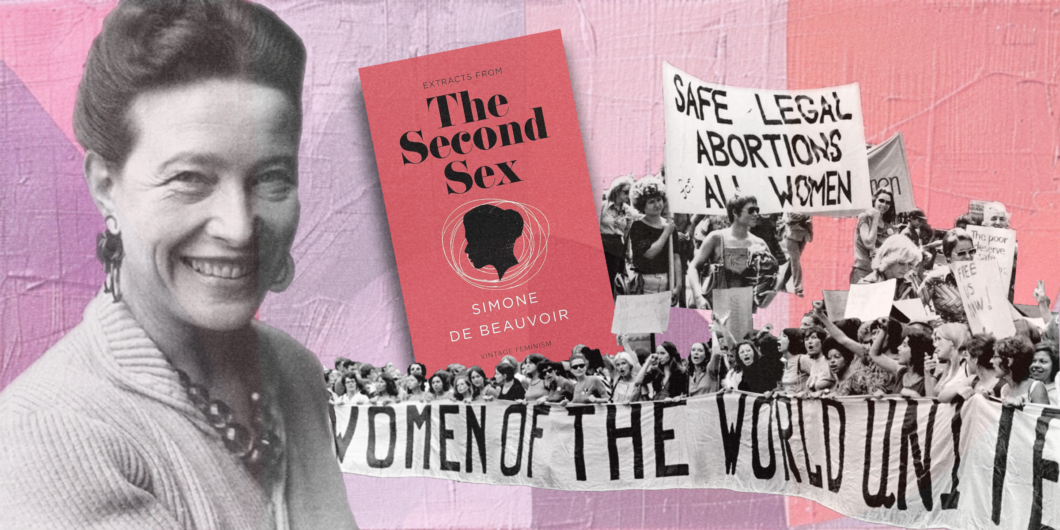

Simone de Beauvoir’s Narcissism

To ask what is a woman, or womanhood, philosophically speaking, will always be a relevant question in our society. Unfortunately, our chaotic world has moved so far from the fundamental questions that many of us are forced to affirm the basic elements of being a woman, or even a human being.

Considering Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in answering these questions may seem unnecessary, however, such a consideration is essential for the continued discussion on womanhood to know the origins of radical ideas that still permeate Western culture.

Contributors to our forum on The Second Sex raised important themes: the idea of otherness, the inherent narcissism of Beauvoir’s work and indeed the movement she helped create, and traditional roles of a woman and their implications for society, among others. It showed that the discussion on feminism will not end, especially today when womanhood and motherhood are attacked and negated from many different directions, particularly by the transgender movement.

Jane Austen and Shamelessness of Feminism

Brenda M. Hafera’s thoughtful essay nicely delineates the issues that surround feminism today. There are three aspects of her essay that I found particularly interesting and fodder for future discussions.

First, Hafera rightly and importantly points out the notion of self-centeredness that continuously hovers above feminism. “Rather than feminism being the single poisonous tree,” writes Hafera, “the rise of expressive individualism … seems to encapsulate our current malaise better. … Expressive individualism is a combination of radical autonomy and the notion that the inner self is the true self.”

By sentimentalizing and deifying motherhood, one loses the sense of fatherhood. In addition, such a message implicitly tells women who are not mothers that they are somehow inadequate as women.

How many times have we heard, “I have to live my truth”? This is especially true of women, who say that they have neglected their needs for decades in an effort to raise children and be good wives. But this would then, inevitably, imply that everything a woman has done in those decades of alleged self-neglect is to be negated. Was her love for her children real? Did she secretly hate her husband? Is she merely dissatisfied because she doesn’t live according to any moral code or faith in God?

Ultimately, the woman who “lives her truth” is a woman divorced from society and family. I am reminded of Stephen Daldry’s 2002 film, The Hours (based on Michael Cunningham’s novel) in which a female character, Laura Brown, abandons her husband and two children (shortly after giving birth to the second child), leaving nothing but a note. Later, it turns out that Laura Brown’s solitary life was not exactly what she hoped for—she moved to Canada and became a librarian. Her son, who never got over this, ends up committing suicide as an adult, gay man with AIDS. Not exactly a happy story but no good came from narcissism. The point is that there will always be a sacrifice at the altar of “expressive individualism.”

The second point in Hafera’s essay is a brief mention of Wilhelm Reich. She invokes Kevin Slack’s description of Reich as the “father of the modern sexual revolution,” and someone who has “influenced New Leftist Paul Goodman.” Although, Reich’s approach to sexuality is certainly questionable, not to mention the fact that he had some wild theories about science, nature, and our relationship to both, he rightly pointed out that Marxism’s “dialectical materialism” and its “vulgarity” was the precursor to National Socialism. As he writes in The Mass Psychology of Fascism, “the Marxists had failed to take into account the character structure of the masses and the social effect of mysticism.” In this case, Reich offers an interesting argument in his attempt to decouple ideology from sexuality, especially eroticism from militarism. By contrast, de Beauvoir is committed to ideology. Reich’s great weakness, of course, lies in his complete rejection of the family structure, which can only lead to sexual revolution.

Lastly, I find Hafera’s final sentence a great starting point for an entirely different discussion, namely the meaning of eros. Although I see literary value in Jane Austen’s work, my objection to her is primarily on aesthetic grounds, secondarily on metaphysical grounds. I am open to other arguments in favor of Austen, but I wonder what exactly is the erotic in relation to Austen? Could we call Austen, very loosely, of course, a “feminist”? Utter lack of eros and humor that is often present in feminism (and certainly in cold, calculating, and humorless Beauvoir) is not an option either, but can we really talk about sexual acts only in relation to morality, or is there metaphysics at play that go beyond societal structures of morality? The erotic and the ethical will always carry a tension, and the erotic is far more complex than politics and ethics.

The Importance of the Female Gaze

Rachel Lu’s essay presents a very balanced view of Beauvoir. Lu is comfortable enough in her own skin to intellectually agree on some matters with Beauvoir despite the fact that there are so many repulsive aspects to her work. Particularly, I found two things that Lu mentions, which could be excellent starting points for yet another discussion and more questions.

Generally, we are told to keep the personal out of intellectual (certainly philosophical!) discussion, but I disagree. This is why I found Lu’s mention of the conversation with her son wonderfully endearing, beautiful, and quite meaningful. To recapitulate, Lu’s son asked why a particular book “was dominated by girl characters.” It was an honest question because her son was looking at the world through his own eyes—the male gaze, if you will. I use the phrase “the male gaze” entirely humorously and not as a scolding of manhood, while completely affirming its existence—just as I completely affirm the existence of “the female gaze.”

In his questioning, Lu’s son pointed to this reality of both male and female gaze. Perhaps part of the larger feminist project ought to be the affirmation of the female gaze, and its definition. Neither are good or bad in their essence. The gaze evades ethics because it primarily deals with our interior life, and this is something that is rarely discussed in feminism because it plunges deeply into politics and ideology (certainly thanks to Beauvoir).

Related to this anecdote, Lu’s argument and agreement with Beauvoir’s “othering” of women is correct. Beauvoir is not wrong, she just can’t let go of ideology, resentment, and bizarre hatred of children. She fundamentally misunderstands the notion of the Other. Yet, as Lu points out, what are we to do with the fact that a woman is treated as the second sex? Being the “first sex,” as Lu writes, isn’t exactly an easy thing either, and it can be quite a burden. In other words, being a man presents itself with great difficulties. Men are “the Other” as well in the eyes of women.

Much of this is tied up in the notion of power. Beauvoir deems a woman “the second sex” because she wants power. On the surface, most of our relationships are exercises in power exchange until they cross that line between the power dialectic and interior metaphysics—a face-to-face encounter that affirms mutual human dignity (Greta Gerwig’s 2023 film, Barbie, showed this relationship superbly).

Moving from power exchange into the recognition of the other’s interiority is akin to growing up (similar to the youthful embrace of Marxism). The trouble is, Beauvoir never grew up.

The Impossibility of Pure Liberty

Elizabeth Grace Matthew’s excellent essay raises many questions about motherhood and womanhood. I like Matthew’s style—she’s funny and free of intellectual affectations of seriousness that plague many writers, yet she presents her points in a very clear and methodical fashion.

Matthew mentions a very important point regarding Beauvoir’s weakness, namely “that pure liberty—not happiness nor purpose nor virtue—is and should be the highest good sought by both women and men.” Pure freedom is an unattainable goal, yet somehow we are obsessed with it. It is not merely a feminist question but a human one as well.

This question is not without its value—inherently, we don’t want to be oppressed and controlled, and so we seek ways to be free. These can often be quite destructive. The path always begins with extreme individualism and narcissism, and it is hardly a mystery how we arrived at this point in our society.

This freedom we so desperately seek cannot even be achieved if we were the last woman (or man) on Earth! We always exist in relation to something else, and that something else (especially if it’s a human being) will always contain within itself a possibility of moral responsibility. There is always something that will push against narcissism. As George Costanza yells out several times in Seinfeld, “We’re living in a society!”

Of course, for Beauvoir, moral responsibility means nothing. Yet, she is not exactly a hedonist either. At least, she could have embraced the life of a female Marquis de Sade, fully and with abandon. Instead, she maintained a façade of a long-term relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre, existing neither here nor there, as it were.

Another point that Matthew raises is about nature. Camille Paglia’s work is essential in comprehending not just feminism but art as well (and our relationship to it), and I was happy to see affirmation of this in Matthew’s essay. As she writes, “For Paglia, it is male-run civilization that controls and mitigates violence (sexual and other), not that it creates it.” Feminism (and especially today’s conservatism) needs to admit there is something violent about creation itself, and although much of the human task is about curbing our passions, we have to comprehend the unpleasant parts of being human. At the same time, we have to realize the limits of freedom.

Lastly, I appreciate Matthew’s points about sentimentalization of motherhood. As she writes, “I find this sanctification of maternalism patronizing and repugnant in much the same way Beauvoir and Paglia do.” There is a bizarre obsession in our society today to go back to the “olden days” of the 1950s when women loved doing house chores and raising perfect kids. I think these same people have looked at too many Time magazine ads from the 1950s. This is not a reality, and certainly should not be a reality today.

By sentimentalizing and deifying motherhood, one loses the sense of fatherhood. In addition, such a message implicitly tells women who are not mothers that they are somehow inadequate as women. Ironically, this creates a further rift between women and men.

Once again, we face the same problem and question that came out of The Second Sex, namely, can one woman speak for all women? For me, the answer is no, but the question itself poses bigger challenges that are not necessarily feminist in nature at all.