Freedom cannot long survive perpetual, chronic, and largely bogus outrage.

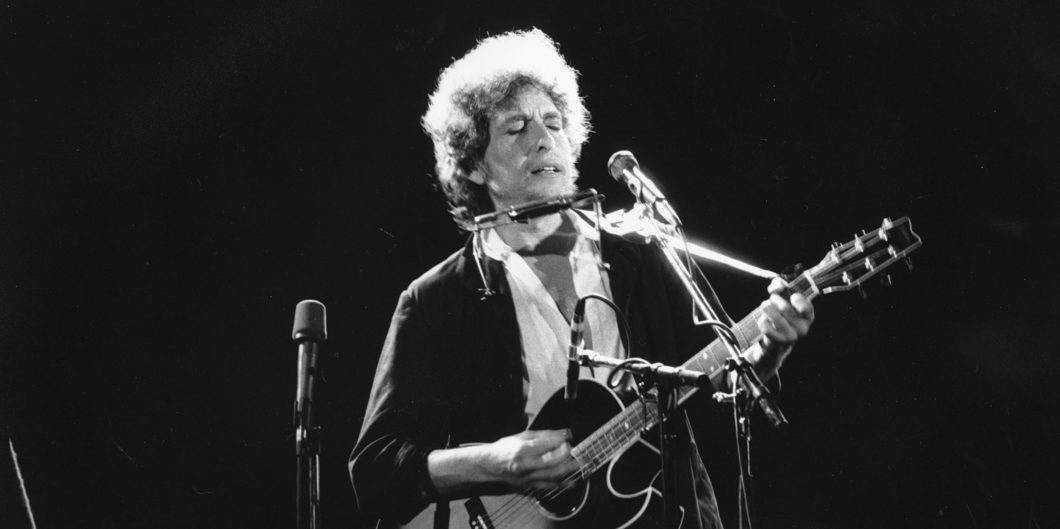

Bob Dylan’s Back Pages

Where is Bob Dylan when we need him?

His anthems “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1963) and “The Times They Are A-Changin” (1964) were an inspiration to the Civil Rights movement, and a guide for the 60s generation. Paul McCartney confessed that the evening he met Dylan, “I got the meaning to life.” U2’s Bono said that “the voice of a generation” was “the voice of all generations.” Whether Dylan deserved the Nobel Prize for Literature is debatable, but a conclusion is premature without reading his Nobel Lecture tribute to music and literature.

Although Dylan’s lyrics and singing style made him a legend, it’s not always evident how elegant some of his songs are until someone else sings them. Such is the case with the reflective “My Back Pages” (1964), whose author, at an exceptionally early stage, was learning crucial lessons about social change. It was The Byrds’ version that was performed by a remarkable array of superstars at the 30th Anniversary Tribute to Bob Dylan at Madison Square Gardens in 1992, with The Byrds’ front man Roger McGuinn singing the first verse. Dylan sings the fifth stanza, and at that stage of his career, his iconic gravelly voice was, at times, giving way to something a little more like walking on gravel.

Sometimes Dylan’s lyrics are brilliant; occasionally they seem like so much jabberwocky. Is “Mr. Tambourine Man” (1965) mystical, hallucinogenic, or is Dylan just having fun with words? He may not know himself, and sometimes he’s just looking for a rhyme or a cadence.

The tone of “My Back Pages” song is confessional, equal parts chagrin and humility derived from experience, all captured by the pithy one-line chorus, “Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” The song notes the pitfalls of the revolutionary, who, unlike Dylan, may never acquire self-knowledge. The song describes the militant self-righteousness born of the purist’s cold moral certainty:

In a soldier’s stance, I aimed my hand/At the mongrel dogs who teach

Such angry conviction descends into hypocrisy:

Fearing not that I’d become my enemy/ In the instant that I preach.

The hypocritical posturing is punctuated by the admission that the singer demands an end to “hate”—in a voice that exudes hate:

Half-wracked prejudice leaped forth/ “Rip down all hate,” I screamed.

Dylan’s insight into “equality” in a time of impassioned upheaval is remarkably prescient. Those who pursue equality may sacrifice liberty in equality’s pursuit. The consequence is less liberty and less equality. As the song suggests, freedom may be a mere means to an end, a waypoint in the quest for something more elevated.

A self-ordained professor’s tongue too serious to fool

Spouted out that liberty is just equality in school

“Equality, “I spoke the word as if a wedding vow

The crusader, moreover, is prone to a one-dimensional, naïve view of life’s challenge. The song describes the activist animated by dreams of “Romantic . . . musketeers” guided by “Lies that life is black and white.” There is no need for moral nuance; prudential caution is just delay.

Ethical principles, moreover, are conveniently and confidently self-defined:

Good and bad, I define these terms

Quite clear, no doubt, somehow

A passing line in the first stanza suggests why moral crusades, however well-intentioned, are vulnerable to misdirection, and how they may succumb to the same vices they seek to eradicate. The ethical errand is undertaken “using ideas as my maps.” There is little need to incorporate the lessons of experience: proceeding a priori is more efficient; acting unencumbered by the past, more effective.

“My Back Pages” disturbed music critics and fans alike as many saw it as a recantation of Dylan’s beliefs, an act of political apostasy. But such a harsh interpretation is not necessary: Dylan matured. The reformer was reforming. Revolutions may purport to be for the “masses,” but if individual honesty is a bother, how meaningful can social change be in the long run? Dylan noted that “My Back Pages” was less of a “finger-pointing” song than some earlier compositions; he was trying to write songs more politically complex. But that commentary is self-deprecating. Compared with the harsh judgmental rhetoric of some, neither the earlier “Blowin’ in the Wind” nor “The Times They Are A-Changin’ are mean-spirited, accusatory, or severe.

“Blowin’ in the Wind” is wistful, inspirational, and soulful, as a youthful Stevie Wonder understood. “The Times They Are A-Changin’” is prophetic but empathetic, certainly not a jeremiad. In several places, the song invokes the Gospel paradox that the first will be last, and the last first.

Come gather ‘round, people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You’ll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin’

Then you better start swimmin’ or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’

It is true that Dylan had become somewhat disenchanted with the protest movements, or at least weary of his leadership role, which he never pursued. He confesses to inner turmoil in the penultimate line of “My Back Pages.”

My existence led by confusion boats, mutiny from stern to bow

Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now

Is such moral confusion evidence that Dylan was lost as some lamented? Not at all. But for shallow souls who never experience the virtue that grows out of inner turbulence, Dylan’s confession may be inscrutable.

Dylan sold more than 125 million records. He wrote and performed over 500 songs, and his songs have been covered by other performers over 6000 times, according to his website. Among others, “My Back Pages” has been covered by such notables as The Ramones, Jackson Brown, Keith Jarrett, and The Hollies.

Dylan is worth a great deal of money but he is not slowing down; at 79, he still writes, records and tours. His music, the tasteful Bob Dylan line of apparel, his signature whiskey, and his bright, colorful watercolors and acrylics are available for purchase. Social progress and sharp entrepreneurship are not mutually exclusive. His Malibu home is decorated in a neo-Spanish colonial style.

But Dylan seems okay with all that. If he is guilty about his success, he hides it well. He rather spends the late autumn of his life enjoying the fruit of his labor, his music, and his grandchildren. And perhaps at times, he is pleased with the quiet memory of that time he changed the world.