A Life Well Lived

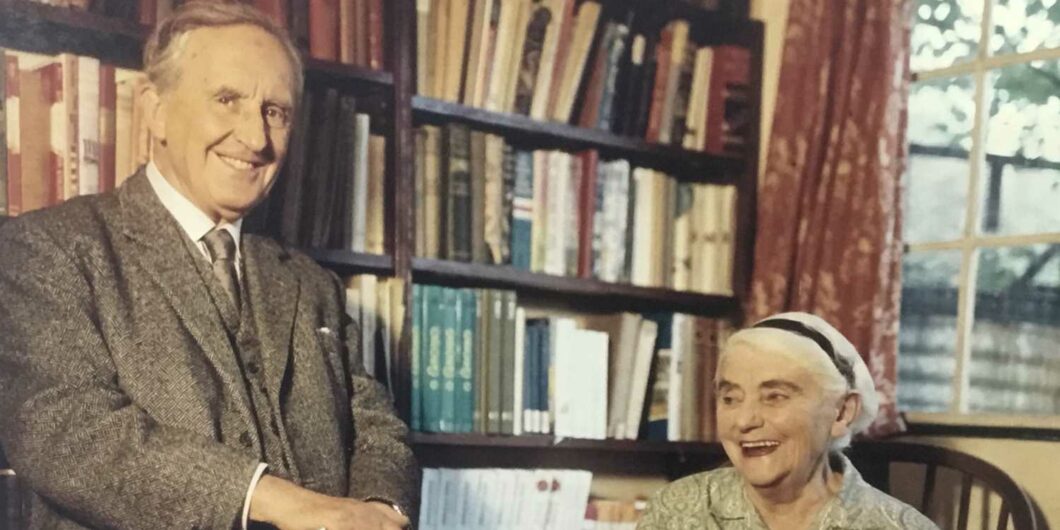

First published in 1981, the 2023 edition of The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, revised and expanded edition, adds 150 letters to the previous correspondence collection and it unfolds, even more than was evident before, a life well lived. His was a life driven by love of family, an extraordinary imagination, and an indefatigable work ethic. It was also a life beset with publishing frustrations, made anxious with two of his sons serving in WWII, and rendered difficult by his own physical maladies and those of his wife, Edith.

The added material to the collection is sizable. The number of letters has increased from 345 to 508 and the page numbers from 463 to 720. For those already in possession of the first edition, the new edition merits purchase. Notable, for example, is the expansion of Letter #131 to Milton Waldman of Collins Publishing (later HarperCollins) in which Tolkien explains at length why the Silmarillion and Lord of the Rings are integrated and should be published together.

Those wanting to start a collection of their own might go to a Christie’s auction and bid on a Tolkien letter as the author’s correspondence is still being discovered here and there. A discount price runs around $10,000; other letters command much more.

The majority of the new letters are either to family or involve exchanges with publishers. Still not included are additional letters to his fiancée, Edith Bratt, later his wife. Let’s hope that their privacy remains intact. Edith Tolkien does appear with regularity in letters to his children as Tolkien reports, with some regularity, on “Mummy’s” health difficulties. Tolkien had his own physical challenges, including neuritis, appendicitis, a broken leg, and “lumbargo” (lower back pain). At times his back discomfort was mitigated by “[t]hree good wallops of Irish whiskey.” Many of the letters are to his son Christopher, who later became his literary executor.

More letters to Tolkien’s son Michael are in this expanded edition, and several are thoughtfully paternal. Michael had been seriously injured in an army vehicle accident and then later suffered from “shell-shock.” Eventually, he was invalided out of the service. He became attracted to a nurse, Joan Audrey Griffith, whom he later married. Accordingly, several letters from his father offer advice on romance. At times, Michael Tolkien wavered in his Catholic faith so that several of Tolkien’s letters are among the most eloquent elegies to the Eucharist found anywhere. There are still few letters to his oldest son John (later to become a Catholic priest) and his youngest child and only daughter, Priscilla, whom he affectionately called “Prisca,” or “Prue.”

Should one wish to read the entire collection front to back, three to four letters a day might be a pleasant pace, perhaps at fireside with brandy. The 2023 collection, like the original, may also be accessed topically through the detailed index, so that, for example, those investigating the relationship between Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, or Tolkien’s comments on the unfortunate creature Gollum, can readily follow those topics. In the digital edition, all endnotes are internally hyperlinked so that it is easy to go from text to note and back again, more efficiently than in the print edition.

Tolkien’s difficulties in securing publication of any of his work, even after the success of The Hobbit, were considerable. In 1952, Tolkien demanded that Collins (later HarperCollins) publish Lord of the Rings without delay or he would withdraw the manuscript. Collins called his bluff and a contrite Tolkien wrote back several weeks later amenable to any proposal the publisher might offer. However, he never saw the publication of The Silmarillion in his lifetime as it was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher.

Those in academics and beyond will find resounding relevance in Tolkien’s concerns about higher education. For example, he notes the “appalling” state of higher education in a letter to his son Christopher. He confesses that “teaching is a most exhausting task.” Surprisingly, Tolkien’s experience taught him that some of the smartest students were the least teachable. He asserted that those students, to use today’s vocabulary, were more easily “radicalized”—or even intellectually corrupted, especially in the “‘climate’ of our present days.” Consequently, teaching those students of “higher intelligence” was so much “wasted effort.” Accordingly, he had grown to prefer “students of B or B+ quality” who, he hoped, were more likely to provide the “soil from which another generation could arise.”

His occasional remarks about democratic governance typically emerge as complaints or warnings. He grumbled about the excessive amounts “HM Customs and Revenue” took of the income from his novels. He wrote to his son Michael of “the claws of the I[ncome] Taxgatherers” and of “the appalling tax-tyranny by which we are crushed.” Tolkien had little hope for a thoroughly secularized democracy. He observed on more than one occasion, “What a rot is democracy without religion!” Tolkien, moreover, resisted literary or political labels. He observed that “[a]ffixing ‘labels’ to writers, living or dead, is an inept procedure, in any circumstances: a childish amusement of small minds; and very ‘deadening,’ since at best it overemphasizes what is common to a selected group of writers, and distracts attention from what is individual (and not classifiable).”

The publication of additional Tolkien correspondence will undoubtedly deepen the friendship between Tolkien’s epic myth and its readership.

Tolkien admits that without C. S. Lewis’ encouragement, the Lord of the Rings might never have been finished, which means that neither would The Silmarillion be published since it rode on the fame of the former. Tolkien deeply mourned the passing of “Jack” in 1963, but Tolkien admitted that “we saw less and less of one another after he came under the dominant influence of [fellow Inkling] Charles Williams, and still less after his very strange marriage.” Lewis and Joy Davidson had been married alongside her (apparent) deathbed in 1957 but she recovered and lived almost three years more before succumbing to cancer.

Tolkien developed a professional and personal dislike for Williams and his work: “I am a man of limited sympathies (but well aware of it), and [Charles] Williams lies almost completely outside them. … I actively disliked his Arthurian-Byzantine mythology.” Tolkien thought, moreover, that Williams’ influence had “spoiled” the third book in Lewis’s space trilogy, although he declines to say exactly why. It could well be because That Hideous Strength departs from the first two volumes in that it is “earthbound,” thus departing from the science fiction genre of Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra, and taking on a dystopian character. That said, on the very day Williams unexpectedly died, May 15, 1945, Tolkien wrote a short but heartfelt letter to Williams’ widow in which he expressed his affection for, and admiration of, Williams.

For a philologist, Tolkien was understandably picky about foreign translations of his work. He noted, for example, that some of his terminology—hobbits, elves, dwarves, gnomes, and the like—did not easily yield cognates, especially in romance languages, and for that reason, he suggested that “hobbits” should remain “hobbits.” He did concede that if an attempt was made to translate such terms into Spanish, they might be rendered, for example, “hobitos” and “elfos.” Even at that, since the Spanish “h” is silent (unless preceded by “s” or “c”), more concessions might be necessary.

Tolkien penned a notable letter in the Autumn of 1971 (that is found in both the initial and also the expanded volumes of his correspondence). Tolkien offers several remarkable observations on his work, leading us to wonder if he thought that he had created something extraordinary. He recalls a letter “from a man, who classified himself as ‘an unbeliever,’ or at best a man of belatedly and dimly dawning religious feeling.” The letter to Tolkien continued, describing an inspirational quality to Lord of the Rings: The individual said that Tolkien had created “a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.” Tolkien mused that “if some sort of … pervading light illumines [Lord of the Rings] then it does not come from him but through him.”

In the same letter, Tolkien recounts a rather mysterious visit from “a man whose name I have forgotten.” In the course of their conversation, Tolkien reports that the individual was staring intently at Tolkien until he suggested that Lord of the Rings was, in some way, inspired. He said, “Of course you don’t suppose, do you, that you wrote all that book yourself?” Tolkien admitted then and thereafter, “I don’t suppose so.” Tolkien even went so far as to admit that he might have been some sort of “chosen instrument”—although he quickly observed that anyone who might play such a role, does so despite their “imperfections” and their “lamentable unfitness for the purpose.”

Equally remarkably, Tolkien continued, suggesting that the publication of Lord of the Rings might have been some sort of watershed moment: “Looking back on the wholly unexpected things that have followed its publication—beginning at once with the appearance of Vol. I—I feel as if an ever darkening sky over our present world had been suddenly pierced, the clouds rolled back, and an almost forgotten sunlight had poured down again.” The author concluded, “Of course The L. R. does not belong to me. It has been brought forth and must now go its appointed way in the world, though naturally I take a deep interest in its fortunes, as a parent would of a child.” He added intriguingly, “I am comforted to know that it has good friends to defend it against the malice of its enemies.”

Indeed, Lord of the Rings has enjoyed many such “friends,” and the publication of additional Tolkien correspondence will undoubtedly deepen that friendship between Tolkien’s epic myth and its readership.