A New Breed of War Poet

In 2002, engaged in urban warfare in the West Bank city of Nablus, the Israeli Defense Force innovated tactically. Instead of advancing in the open streets, they broke holes in buildings with walls perpendicular to the street: this allowed them to move up the street safely, the houses covering them from hostile fire. This innovation had an unlikely origin in the heady postmodern writings of leftist Parisian intellectuals. The Israeli military’s coopting postmodern philosophy started in 1995 when a retired brigadier general of the IDF, Shimon Naveh, founded the think tank, Operational Theory Research Institute. The mission of the think tank was to produce position papers adapting high-level thinking for combat situations. The tactical innovation just described is an example of “smoothing out space,” derived from the anti-state manifesto of Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus. The think tank closed in 2006 after other suggested innovations were ineffective in the Lebanese War.

Naveh is one of a new breed of War Poets. WWI was a civilizational threshold and amongst its consequences was a transformation of literature which gave us the modernist poetry of David Jones and the fantasy world of Tolkien, to name only two veterans who changed English literature and the way we think about war. Today’s war poets include General Mattis, the Defense Secretary in the Trump Administration. In memoranda, Mattis argued that the military certitudes of the Cold War were well and truly gone and recalling the centrality of contingency in the thinking of the great theorist of war, Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), Mattis recommended to the US military artistic creation as the framework best suited to coping with uncertainty.

Mattis was riding a wave coursing through all Western military academies keying war to ideas of art, artists, design, and creative genius. Naveh and Mattis, along with dozens of others—including gaming corporations—argues Anders Engberg-Pedersen, form “a martial-aesthetic avant-garde exploring the uncharted territories of a new literary genre.” The problem is that whilst most WWI war poets ironized war, puncturing its chivalrous pretensions, the new war poets engage in artistic worldmaking to deliver a more potent punch on the battlefield. Their art is “a demiurgic production of war.” Perversely, contends Engberg-Pedersen, our war poets take what is highest in civilization—art—and make it serve barbarism and violence: “As it transfigures violence into artistic matter, military design frames war not as a brutal act of military force and a means of last resort but as a virtuous and even desirable activity to be pursued for its own sake.”

Commander’s Visualization

Engberg-Pedersen is an award-winning professor of comparative literature in Denmark. Martial Aesthetics: How War Became an Art Form is a theoretical supplement to his first book, Empire of Chance: The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things. These books trace a critical change in how wars have been fought. They document that for millennia astrology had been the handmaiden to war. As late as the seventeenth century, the field tent of the commander of the forces of the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years’ War, Count Palatine Albrecht von Wallenstein, included as many astrological charts as it did maps and sketches of troop movements. Engberg-Pedersen’s research tracks war as a field of knowledge. What Wallenstein wanted to know were future events. In the fast-changing world of battle where the fog of war dominates, Wallenstein wanted surety about the consequences of his committing his forces. That he turned to astrology tells us about the belief system of military and political leaders, and how polities then thought about the cosmos. This is not a merely historical endeavour. As wars rage, what militaries believe is the character of the world shapes what we all believe about reality.

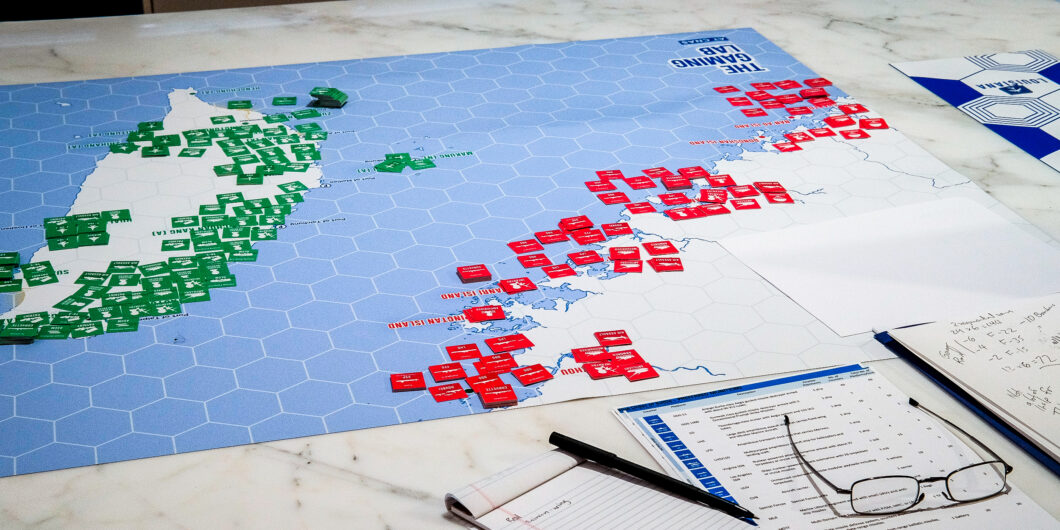

As the influence of astrology waned in the early Enlightenment, war games took over. By playing games, military and political leaders could make predictions about the probable outcomes of their actions. War gaming became a basic tool of war planning, and still is to this day, for example, One World Terrain is a database a bit like Google Maps that allows the military to generate a replica of any space on earth and give troops a role-play experience of combat in any locale. Disturbingly, the US military’s war gaming for the battle for Taiwan has reportedly consistently shown the U.S. being horribly mauled.

Though ultimately prevailing, the war games show the dreaded outcome of sunken aircraft carriers.

Critical to any war game is how it is designed. The trick is to corral a vertiginous number of contingencies in an elegant visualization so a narrative can be delivered down the chain of command as to what is expected of all components of the army. When war gaming replaced astrology, art came to the forefront of war planning. Enlightenment designers of war games looked for guidance from prevailing aesthetic theory and this fusion of high design and war culminated in On War. Clausewitz’s On War (1832) remains basic reading at war colleges throughout the West—his idea of the culminating point has been one of the most cited during the Ukraine War. Importantly, Clausewitz’s volume—replete with aesthetic terms—is the most famous, but it is not unique. Enlightenment war manuals are chock-full of talk of art, artistry, and the genius of the coup d’oeil, the gifted commander’s capacity to distill critical information from the chaff and to visualize the battlescape.

Romancing the Tabula Rasa

The problem is that whilst On War is full of subtleties, other volumes of the genre are not. Dominating the field were Prussian manuals but these became captive to German Romanticism and proffered “the enchantment of war as an art form,” with the “systematic erasure of brutality, suffering, and death.” Engberg-Pedersen states, “The merger of war and aesthetics in these texts of Prusso-German military theory, however, is pushed even further in US military thought.” What facilitated this continuity and intensification?

German martial aesthetics relied on Romanticism’s celebration of creative genius and, also, a Formalism positing the world as a tabula rasa, an empty canvas ready for military worldmaking. The toxic brew of Prussian Romanticism and Formalism is unmistakable in Western military colleges today, argues Engberg-Pedersen. Globalization flattens out geographical unwieldiness leaving a plain canvas for the operations of “the martial techno-aesthetic apparatus” of the West’s military-industrial-design complex to make good “the generative view of war.” Today, “the wargame is the birth of the real.” The design gurus of gaming companies, along with the military’s own artistic avant-garde, have developed operational aesthetics wherein “a new and radical aesthetics” becomes “an ontological machine.” Martial Aesthetics excavating the underlying dynamics of the contemporary military scrambles some preconceived ideas. Likely, most have the impression that the art scene in NYC or LA has nothing to do with Camp Lejeune or the impression that STEM has displaced the humanities in our military academies, but both impressions are wrong.

Clausewitz observes that all militaries collect trophies, and we hope and expect that our military only collects the decent, not the hideous, ones.

The grim upshot is reprimitivism. Traditionally, aesthetics helped polities cultivate tolerance, but martial aesthetics is “an obscene perversion of the traditional field of aesthetics,” a “merger of war and aesthetics [that] is increasingly blurring the line between civilization and barbarism.” Fuel for this fire is a striking apocalypticism that pervades the genre. Engberg-Pedersen points to the writing of US Marine, Phil Klay, and his 2020 novel Missionaries—a personal favorite of President Obama. A central character in the novel is a drone mercenary who goes around the world from “one digital battlefield to the next” and who self-consciously acknowledges that he has zero understanding of the war zones in which he sells his talents. This apocalyptic literature of the world laid to waste by payloads delivered invisibly by nomad “warriors” is, believes Engberg-Pedersen, “a not-too-subtle propaganda tool for increased militarization.” Contemporary martial literature “fails to imagine a complex human environment in any credible detail” and the evidence is that “martial aesthetics has not imagined a single world one would like to inhabit.”

Is There a Case to Be Answered?

The West’s worldview is being nourished by “the truly strange character of contemporary warfare.” The poets of this worldview are military designers working on gaming, position papers, memoranda, short essays, and novels. Engberg-Pedersen’s charge is that “creative imaginary worlds have themselves served as engines of violence and destruction,” but has that case really been made? I wonder whether Engberg-Pedersen has not both oversold and undersold martial aesthetics.

I wish Engberg-Pedersen rigorously held fast to Clausewitz’s position that war is an instrument of politics. He is aware of this position, but talks loosely at times, e.g., “the total military-political work of art created by the war artist.” Clausewitz endorses no such hybrid. He is explicit that though generals can be in cabinet meetings they must never be permitted to dominate the discussion. Engberg-Pedersen’s hybrid “military-political work of art” oversells the role of the military creative genius: “War, in this conception, emerges as the highest creative expression of genius.” This might be true in the domain of the military but that domain, says Clausewitz, is secondary to the political.

When speaking of this final, decisive domain, Clausewitz does not use the Romantic language of artistic genius. That language is reserved for the generals, and crucially, in matters of strategy, the creative design of the general is limited to the gravitational center of war, the engagement. Unless the general is also a political leader (Napoleon), the larger strategy that engages the geopolitical situation—the end to which war is the means—is beyond the purview of the general. Clausewitz, for one, would be skeptical that war has the scope of influence with which it is credited by Engberg-Pedersen.

I also wish that Engberg-Pedersen had fleshed out more of Clausewitz’s idea of the coup d’oeil. This concept is not just the brilliance of visualization by the military genius but the stamina to see a pathway through the confused epistemology of the battlescape. Clausewitz thinks the human is a naturally timid animal, so the task of a great general is steady nerves when receiving an enormous volume of knowledge, most of it fake or distorted, from panicked subordinates. The coup d’oeil is more than just an aesthetic, it is the product of a toughened viscera. It owes much to an inner fortitude capable of blocking out panicked chatter. Engberg-Pedersen oversells the aesthetic dimension, therefore, but, in another critical way, undersells it, too.

For example, Engberg-Pedersen garbles Plato’s Laws. He reports as Plato’s position that play happens during peacetime, not war, and so Plato’s position is more moderate than that of the wargaming Enlightenment. However, what Plato in fact argues is that the best time to play at war is when at peace so that the body is well prepared for war. Playing games, like wrestling, readies the body for war. Aesthetic preparation for war is critical, therefore. This is why the Laws begins with the topic of war and goes on to explain how religious rituals, dancing, singing, and sports deliver the necessary aesthetic training—ultimately a harmony of body, mind, and spirit—to excel in combat. Aesthetics plays the critical role in war, according to Plato, and this is why Engberg-Pedersen undersells it to Plato’s mind.

Curiously, more than aesthetics, von Clausewitz’s classic is pervaded by the language of accountancy. Engberg-Pedersen does not dwell on this point, but it would serve the wider argument he is making. He stages the book as a contribution to the European critique of capitalism. Per the German thinker, Joseph Vogl—the author of The Specter of Capital—“moral imaginaries,” like Smith’s invisible hand “are pervasive and performative” in commercial civilizations. Our poets “make and they shape the wars that militaries seek to realize” and “they are the creative demons that now inhabit the war machine.” The commercial civilization of the Enlightenment is thus not a crystal-clear vessel of transparency universal facilitating people’s autonomous choices. Does this wider argument throw the baby out with the bathwater?

Can any civilization, but especially one like ours, really dispense with martial aesthetics? After all, civilizations are about beauty, decoration, adornment, and fashion. These are the themes addressed in Plato’s Laws. Unavoidably, our military must reflect the dominant theme of our civilization, which is design. As Adam Smith explains, modern liberty grew from the vanity of aristocratic landowners selling their land to afford gold buckles for their shoes. Clausewitz observes that all militaries collect trophies, and we hope and expect that our military only collects the decent, not the hideous, ones.

Comparing civilizations, David Hume poses the question of whether you would want to be taken captive by Genghis Khan or an eighteenth-century French officer. Hume prefers to fall into the decorous hands of the French officer. Assuming Clausewitz’s caution is observed—that the political control the military—once the dogs of war are released, I suspect we would still give David Hume’s answer to his own question.