Scholars and pundits are suddenly interested in the section disqualifying insurrectionists from offices. But text and history don't offer clear answers.

A President of Many Talents

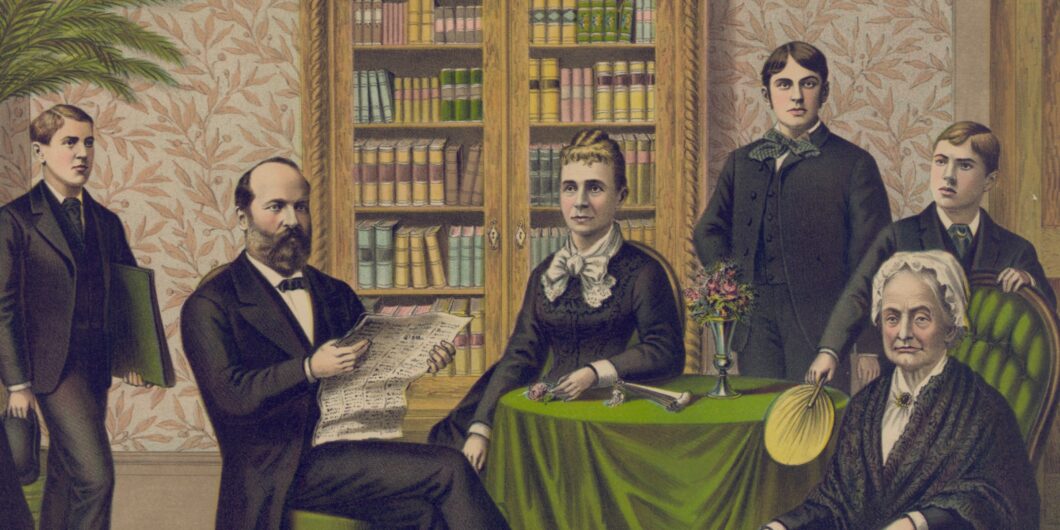

Twelve military generals have been elected President. Five party leaders in Congress have ascended to the chief magistracy. But only one President has been both. Only one has published an original mathematical proof. The man with all these striking accomplishments is James Garfield. The reason that he lingers in obscurity despite all his talents is the brevity of his presidential tenure. Garfield was shot three months after taking office and died ten weeks later, making him the President with the second shortest service after only William Henry Harrison.

Yet if his presidency is necessarily of limited interest, his life is fascinating both because of his multifaceted acumen and its window into mid-nineteenth-century America. It is thus worth having a modern account of the man, and President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier is an illuminating effort by a rookie biographer, C. W. Goodyear. Goodyear provides most of the information necessary for a balanced judgment of a politician who saw more deeply than most into the essential political fault lines of America in his day—even if he may have been too calculating in his need for popularity and power to repair them. But at times, Goodyear fails to fully investigate significant incidents in Garfield’s life, whether because of a misplaced sense of delicacy or political correctness.

Socially Mobile in Antebellum America

Garfield’s rapid emergence on the national stage testifies to the openness to talent that marked the young republic. He was the last President to be born in a log cabin, and his father died shortly after his birth. Despite the valiant efforts of his mother Eliza, who even put her back to the plow, his family was poor, almost destitute. Yet his mother insisted he go to school when he was not working in the fields or managing mules that towed boats on the Ohio Canal. Despite this limited time for education, he distinguished himself in all his classes and in debate. He was the rare student who was both brilliant and popular.

After a couple of years of teaching younger students, he went to the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute in Ohio. The college was run by the Disciples of Christ, the Protestant sect in which he was raised. As Tocqueville recognized, such associations were the beating heart of America’s civic republic and for Garfield, they were the springboard to success. At the Institute, he again excelled—this time in his courses of Greek and Latin, all the while earning money as a janitor. For his final two years of college, he transferred to the more established Williams College in Massachusetts, graduating Phi Beta Kappa and as the salutatorian. He had to work his way through there as well, going around New England earning money as a preacher at Disciples congregations—a vocation that honed his already considerable oratorical skills.

The Western Reserve then lured him back as a professor and by age 26 he had become its president. But Garfield was too ambitious to remain an educator. Abraham Lincoln, who had a quite similar background, was said to be “an engine that knew no rest” and that could have just as easily been said of Garfield. A wealthy fellow Disciple, Harmon Austin helped him seize an opportunity to run for state Senate. This and other incidents show that Garfield was not a man of unimpeachable integrity: At Austin’s request, Garfield signed a teaching certificate for Austin’s niece, even though she did not meet the requisite qualifications. Later as a member of Congress, Garfield was caught up on the fringes of the Crédit Mobilier Scandal, when he appeared to accept shares from a company that became bankrupt through fraud.

When the civil war broke out, he sought a commission despite having no military experience. Although he craved high rank, Garfield reluctantly accepted a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel, commanding Ohio’s 42nd Infantry Regiment. Most politicians turned Union officers were dangerous duds. But unlike the typical politician, Garfield was a genius, probably rivaled in sheer intellect only by Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams among our Presidents. He rapidly distinguished himself, drawing up the battle plan for General Don Carlos Buell’s invasion of Tennessee. He then beat the rebels at the Battle of Middle Creek. Despite the relative modesty of the victory, he was lauded across the nation for winning when the Union’s fortunes were at a low ebb.

Promoted to brigadier general at the age of 31, Garfield then quickly cashed in on his popularity by getting elected to Congress. One reason for his leaving the army was undoubtedly ambition. He surely sensed that he could not easily gain higher command given his lack of military education, and he may have recognized his limitations. But another reason was more foresighted and less personal: even in 1862, he wrote that the problems of the war would pale in comparison to the problems the nation would face after peace. He recognized that political, not military, struggles would ultimately determine whether and how society could be put back together.

Reconstruction Politics

Garfield began as a radical Republican. Even if not as personally hostile to Andrew Johnson as some other radicals, he joined in the fight to have a reconstruction that would truly emancipate the former slaves, passing legislation to suppress the Black Codes that many states enacted to try to put them back into a state of peonage. But the most interesting story in the entire biography is that over his eighteen years as Congressman, Garfield became less radical, instead joining the more “liberal” and reformist Republicans who took a less hard line toward the former Confederate states.

It has become fashionable to dismiss the waning of Reconstruction as simply a product of racism. But at least for Garfield, and probably for many of his supporters, this verdict is too simplistic.

As with most politicians, his motives for the change were mixed. One was undoubtedly political. The harder-edged reconstruction was becoming a vote-loser, not only among Southern whites, but among Northern whites who were not eager to pay for the continued military occupation of the South. But Garfield also became concerned about the risk to civil liberties of some of the laws suggested by the most radical of his colleagues. For instance, he helped argue the famous case of Ex Parte Milligan that held it was unconstitutional to try civilians by military courts if civilian courts were available. Finally, he believed there were other pressing issues, and forging the consensus to address them militated against very divisive Reconstruction policies. Becoming chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, he focused on preserving the gold standard against growing populist attacks. He supported civil service reform against the Republican Stalwarts who wanted to continue to use patronage as a source of political power.

It has become fashionable to dismiss the waning of Reconstruction as simply a product of racism. But at least for Garfield, and probably for many of his supporters, this verdict is too simplistic. He continued to support rights and indeed federal appointments for African Americans. If the Supreme Court had enforced the original meaning of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to prevent discrimination in civil society and in voting, as it should have, Republicans like Garfield would have likely welcomed their decisions.

At the 1880 Republican Convention, Garfield came pledged to support the nomination of Senator John Sherman of Ohio. He gave a brilliant, extemporaneous nomination speech, in which he argued that the Republicans needed a calm and steady candidate who would reassure the nation that the confusion and corruption of the Grant administration would not return. He mentioned Sherman’s name once only at the end, and observers recognized that he was also describing his own qualities. This is the speech in American history that most resembles Mark Antony’s famous funeral oration. It had a surface cover that concealed its real purpose. And it was successful. Garfield steadily gained support at the convention and was selected as the nominee. He then won a close election in the fall against another former Union general—Winfield Scott Hancock.

Death in Office

Garfield’s assassination is the best-known part of this life. And Goodyear tells the story well. For instance, he introduces, but does not name, a mysterious man who makes speeches for Garfield before the election. Later in the biography, this man shows up in Washington demanding in an increasingly unhinged manner a federal position as a reward for his service. The man, finally identified as Charles Guiteau, then shoots Garfield at a train station, crying that “I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President.” Vice President Chester Arthur was of the Stalwart faction, and Guiteau, in his derangement, thought he would then get a patronage appointment. Ironically, the one clear result of Garfield’s murder was to assure the passage of civil service reform, since the attack seemed a direct result of the patronage system. As Goodyear notes, for the cause of civil service reform, Garfield was worth more dead than alive.

Goodyear also ably recounts the dreadful treatment that Garfield received at the hands of arrogant and ignorant doctors. They repeatedly probed his wound with dirty hands, giving him an infection from which he slowly and painfully died. If they had done nothing but staunch the bleeding, Garfield would likely have recovered.

Some Errors of Judgment

Goodyear is a first-time biographer and, while the book is mostly well done, some of his choices are irritating, even baffling. Garfield had an extramarital affair in his twenties, knowledge of which became such a potential liability that he went to New York to retrieve the letters long after the affair had ended. But only on that later trip to New York do we learn the name of the woman, Lucia Calhoun, and we are told nothing about her or the nature or duration of their relationship. And that is not because there is nothing to be told. Lucia Calhoun (later Runkle) became a prominent editorial writer, one of the first women ever to hold such a position in the United States. Garfield was a preacher in a conservative protestant denomination. Describing more fully his attraction to a bright, young, emancipated woman could have illuminated more about his character and even his social views.

At one point, as a member of Congress, Garfield went to Montana and became involved in persuading the Salish Tribe to relinquish some of their ancestral lands. Unfortunately, Goodyear is not clear about how and why a member of Congress was given such an anomalous executive responsibility. But Goodyear does write “how he did, so can, and must, be summarized by an outsider only in brief. Only the modern-day Salish are qualified to relate the tragedy of their ancestors’ relocation in the voice and depth it deserves.” This approach exalts identity politics over the search for historical truth. Evidence is open to everyone, whatever their race, and we will get closer to the truth if people of various ideologies and precommitments sift through it. Goodyear is correct that Garfield’s performance as a negotiator here deserves serious scrutiny, but he is wrong to think that priority should be given to the Salish’s views any more than we should only consider the voices of peasants in evaluating feudalism. His sententiousness also makes the reader fear that Goodyear is not giving us a fully objective picture in his brief account of the negotiations.

Goodyear also only spends two sentences on Garfield’s published proof of the Pythagorean theorem. How original and path-breaking was it? How did Garfield come to write it while serving as a member of Congress? Indeed, this achievement comes like a bolt from the blue, because it is the first we have heard of his mathematical interests.

Nevertheless, on the whole, Goodyear’s work is a very credible first effort. And he is to be congratulated on choosing to revivify a president whose life deserves fuller consideration for its own merits and for the (flattering and unflattering) light it sheds on nineteenth-century America.