Chasing the Presidency

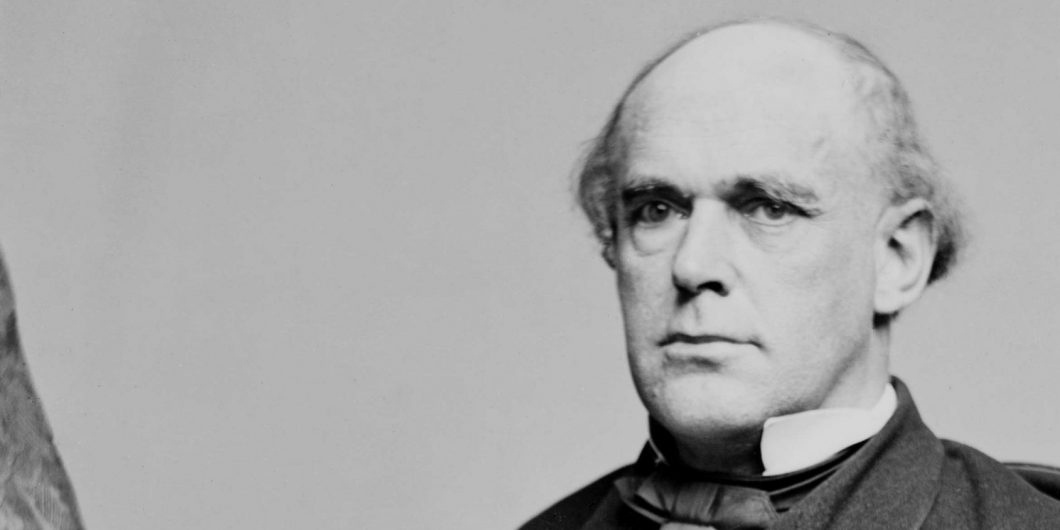

In Rashomon, Akira Kurosawa tells the story of a brutal crime from multiple viewpoints, revealing the varying perceptions and motivations of the witnesses, while leaving any final truth uncertain. Walter Stahr has accomplished something similar with his three biographies of Abraham Lincoln’s key cabinet members—Secretary of State William Seward, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. Here we see antebellum America, two decades of the anti-slavery movement, Lincoln as president, and the Civil War from three perspectives, each providing a unique angle.

It’s a multi-volume version of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, but unlike Goodwin’s focus on the political genius of Lincoln, Stahr takes the measure of Lincoln’s understudies, and finds something of the genius in each of them as well.

Seward was, in Stahr’s description, “indispensable” to Lincoln politically. Stanton raised the Army and served as a shield for criticism of the administration’s conduct of the war and violations of constitutional rights.

Lincoln socialized with Seward. He spent more time with Stanton than with any other cabinet official, largely in the War Department telegraph office, where one official would describe the two men as “utterly and irreconcilably unlike” while asserting that “no two men ever did or could work better in harness.”

But, as Stahr writes in the latest volume, Salmon P. Chase: Lincoln’s Vital Rival, Lincoln was neither socially nor politically friendly with Chase. The Treasury secretary mostly served his president well and often expressed high praise of him. Stahr calls their relationship “polite and professional.” Chase was an effective administrator, working with Congress to raise the money to pay for the war and establish America’s first national currency. But he left many with the sense that he considered himself Lincoln’s intellectual and political superior, and that he was owed the reward of the presidency for his long toiling in the free-soil field while declaiming any ambition for it. Pondering a race against Lincoln in 1864, he argued that “a man of different qualities from those the president has will be needed for the next four years.” In Chase’s view, Lincoln was “not earnest enough, not antislavery enough, not radical enough.”

It was a fair analysis, as far as it went. Chase’s toil was longer and more righteous than any of the other serious presidential contenders in 1856, 1860, or 1864, Lincoln and Seward not excepted.

His life in the anti-slavery movement stands at the heart of the book, an attempt to rescue him from the popular oblivion that often befalls those who fail to become president. It’s a mission that deserves success because Stahr has an important story to tell about Chase’s central role in the on-the-ground political work of the anti-slavery movement and the building of three political parties.

A Party Man

That anti-slavery career began as a lawyer representing fugitive slaves. Stahr is a lawyer and he recounts Chase’s most important courtroom appearances. The sections on the fugitive slave and post-war Reconstruction cases are some of the best writing in the book.

Chase argued that the Constitution’s Fugitive Slave Clause was a mere compact among the states, not a grant of power to Congress. That would have severely limited, if not eliminated, congressional authority to legislate on the issue had the courts been willing to accept Chase’s interpretation. He opposed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 as a moral abomination as well as a violation of the constitutional rights to due process and a jury trial. When Congress passed and President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act into law in 1854, repealing the Missouri Compromise and opening new territory to slavery, Chase was among the first national figures to call for a new anti-slavery party to rise in its wake. And, the father of two daughters, he was an early supporter of women’s rights.

Historian Eric Foner has called Chase, a Democrat at heart, the intellectual godfather of the Republican Party, and it’s a fair analysis. He was the first Republican governor of a major state; an organizer of the first national party meeting; and a consistent proponent of a true amalgam of anti-slavery groups when others pushed for a purity that would have satisfied egos but led to electoral defeat.

Long before the death of the Second Party System in the mid-1850s, Chase had played a role in the formation of both the Liberty Party and the Free Soil Party, protest movements that brought small factions to the electoral process but never threatened to win power. Having been down that road twice, he saw better than most the importance of including all factions, including anti-Catholic nativists, in the emerging Republican coalition. He took considerable grief from more radical friends, but stood fast.

But all that work did not win him a nomination for the presidency or vice presidency, even though he had been mentioned as a potential candidate almost from the first moment of his involvement with the Liberty Party in 1840. The Free Soil Party turned to more famous names in 1848 — former President Martin Van Buren and Charles Francis Adams, a son and grandson of a president. In 1856, Republicans chose explorer John C. Fremont in part because he did not have a public record; Chase’s long work in support of the cause was a detriment. In 1860, Chase and Seward were both viewed as too extreme to carry the key states of Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Illinois, and lost out to the more moderate Lincoln.

As is usually the case in politics, there was more to it than that. Chase had other challenges, especially a sense among his Republican colleagues that, despite his crucial role in the formation of the party, he was never quite one of them. He had long professed Democratic positions on issues such as banking, tariffs, and the size of government. A political deal he made with Democrats early in his career left a bad taste in the mouths of Ohio Whigs that never fully went away. A similar betrayal a few years later left Free Soilers wondering about his loyalty.

Even allies were put off by his combination of sanctimony and ambition. Radical Republican and fellow Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade said Chase was “a good man, but his theology is unsound. He thinks there is a fourth person in the Trinity: S.P.C.” John Hay said Lincoln was “much amused by Chase’s mad hunt after the presidency.”

Moralist and Politician

Chase was a politician in every sense of the word, always casting his motives in the best possible light, always claiming a willingness to step aside for another in support of a higher cause. Even as chief justice, he was deeply involved in electoral politics and legislating. But he was also a moralizing idealist who wrestled with his own ambition. Biographer Frederick Blue comes down on the side of defending Chase against charges of excessive ambition; John Niven sees Chase as a moral man swamped by ambition.

Stahr exhaustively (sometimes exhaustingly, at nearly 900 pages) details both elements of Chase’s personality and leaves it to the reader to judge. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who stood outside the political process, had more faith in politicians trying to be moral than in moralists trying to be politicians. It’s fair to say Chase fit more snugly in the latter category, motivated by a sincere religious faith that guided his agenda and helped him deal with a staggering series of personal tragedies—by his mid-50s, Chase had lost both parents, three wives, four children, and nine brothers and sisters.

Salmon Chase did more than his share of work paving the long road to liberty and equality.

Like any politician, Chase had his moments of opportunism. Abolitionist Wendell Phillips accused him of failing to do all he could to save escaped slave Margaret Garner, who had reached freedom in Ohio. Garner had killed her own daughter rather than see the child returned to slavery, and was eventually returned to the South. He eased off a long-time insistence on Black suffrage in 1868 when, while serving as chief justice, he sought the Democratic nomination for president from a convention whose delegates included Nathan Bedford Forrest and Robert Barnwell Rhett. He joined Democrats in opposing military governments in the former Confederate states—in effect surrendering the newly enfranchised freedmen to the tender mercies of their former masters, while still claiming to support the Republican ideal of enfranchisement. Stahr notes that it is hard to disagree with Henry Ward Beecher and Frederick Douglass’ assertion that “Chase’s ambition for the nomination in 1868 made him forget his friends and his principles.”

Still, few men in elective office in antebellum America worked as long or as diligently in pursuit of liberty as Chase.

He led a life we don’t see much anymore—a long, slow, steady devotion to a cause that starts with little popular support, grows steadily but not remarkably in public acceptance, and finally yields fruit. That still happens in American politics, but the people who make it happen tend not to become president. Today’s politicians are in too much of a hurry to devote that much energy to something so mundane as party building or as risky as an ideological crusade. Political celebrity today is bought with other currency, including the nonpolitical kind.

There are examples of both in the 19th century as well. Chase’s loss of the Republican nomination in 1856 was in part a defeat at the hands of celebrity. Fremont, the famous pathfinder, had achieved almost nothing in politics but was much more famous than Chase. James Buchanan, like Biden, had a career that spanned close to half a century and eventually won the presidency, but had no great accomplishment or cause attached to his name.

Freedom National

The time may be ripe for a new Chase biography; his sometimes-sanctimonious personality should be a good fit for a moment in history when obnoxious certitude in politics is in vogue (although Stahr is successful in debunking the notion that Chase was utterly humorless). Perhaps even more so, Chase’s early and fervent dedication to the cause of racial equality at a time when taking such a stand entailed considerable political and even physical risk should endear him to modern audiences, who can take such stands risk-free.

But in a more significant way, Chase is out of step with today’s racial warriors. Chase believed in the idea of “freedom national”—Stahr even credits him with originating the term in a speech delivered in 1850, two years before the more famous usage attributed to Charles Sumner. Chase believed the Constitution was grounded in the idea that slavery was a local and sectional institution, protected where it existed but not to be introduced anywhere else. After two failed attempts at party building, he played a central role in founding a major political party that held that belief as a core conviction. “Chase realized,” Stahr writes, “that Americans would not join a party whose leaders denounced the Constitution as a compromise with slavery, and who burned copies of the Constitution at public meetings.”

It has been a generation since the last Chase biographies—Niven’s Oxford University Press book more than a quarter-century ago (he also edited Chase’s papers, published by Kent State University Press), and Blue’s 1987 biography (also from Kent State). Before that, there had been no serious biography of Chase since the end of the 19th century.

Stahr’s lengthy study reaches higher and accomplishes more than any previous work. His prose is straightforward, his arguments lawyerly. He presents the facts, states his case, and moves on to the next case. Extensive research is backed by a firm grasp of the times of which he writes. With Chase, even more than with Seward and Stanton, Stahr has again presented a fully developed portrait of a major figure who has not garnered as much historical or biographical attention as his contributions warrant.

Salmon Chase did more than his share of work paving the long road to liberty and equality. That might not have entitled him to the presidency, but Stahr’s biography makes a worthy case that he deserves to be remembered and honored for his toil.