Helprin proposes a military buildup to facilitate a strategy of counter-pressure and deterrence.

China's Regime Rewrites World War II History

With a clarity informed by thorough research, Rana Mitter reports on World War II’s growing importance in China’s popular culture and official self-representation. American readers may find his account in China’s Good War perplexing, for much in the Chinese view strikes us as distorted or self-contradictory. Now, it must be admitted that no nation treats its wars with scrupulous fidelity to the whole truth. In the V-E Day speeches with which the Allies congratulated themselves for defeating Hitler, it was not customary to mention the Vichy regime, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, or the America First movement. But one of the main takeaways from this book is that the Chinese understanding of World War II undergirds claims they now make on the rest of the world. As rude as it may seem to challenge misconceptions of the type to which we all are prone, we cannot finesse the disagreement here.

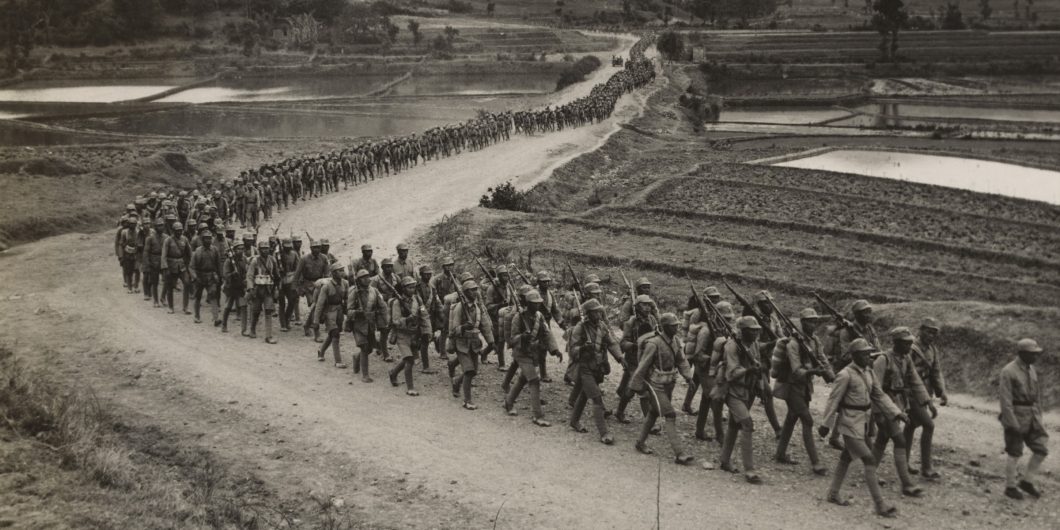

At issue is the traumatic period from 1931 to 1949. First, let me offer a synopsis of events in China from an American point of view: Sovereignty was fuzzy in the three mineral-rich provinces which we call Manchuria. Russians and Japanese traded elbows as they struck deals with a Manchu warlord until the Japanese had him killed in 1928. The next year, Chinese and Russian armies fought for control of the railway. In 1931, initially without civilian authorization, Japanese officers seized the region. They met no effective resistance and soon installed a puppet government. There ensued an uneasy and, for the Chinese, humiliating peace. In July 1937, high-handed behavior by Japanese troops stationed (more or less with Chinese consent) near Beijing sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War (the first one having been fought in 1894-95). Beijing fell almost at once; the capital at Nanjing fell by year’s end and suffered large-scale Japanese atrocities.

In several provinces Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist regime, though authoritarian, had only tenuous control. The regime was also handicapped by economic underdevelopment and led a faltering war effort that lost most of the eastern cities to the invaders. Reluctantly, Chiang made common cause with his foe, the guerrilla leader Mao Zedong, but there were times when each seemed as interested in weakening the other as in defeating the Japanese. A prominent statesman led a rival government (today vilified as a puppet regime) based in Nanjing, and a significant part of what we might call the mandarin class joined, or acquiesced in, this Chinese Vichy. But the people did not fold; doubtfully led and poorly supplied, they endured hardship and fought on. For the Japanese, the war became a stalemate.

After Pearl Harbor, the US acknowledged China as an ally and provided equipment, money, and some training—and, later in the war, considerable airpower—but it was clear that US priorities lay elsewhere. Expecting Chiang’s China to remain friendly and help stabilize postwar Asia, the US accorded this divided, impoverished, and embattled state an exaggerated dignity at the Cairo conference and, in 1945, at the United Nations. But after Japan surrendered as a result of atomic bombing, the competition between a war-weary Chiang and the wily Mao resumed bloodily. American efforts to reconcile the factions failed and the civil war ended in the Communist victory of 1949. The Korean War then sealed China’s estrangement from the US-led international order.

The Chinese have a very different picture of these events, one that has changed over time. For the first three decades of the People’s Republic, the War of Resistance against Japan (as it is called in China) was downplayed except to laud the contributions of Communist units while suppressing the major role of the national army. On at least two occasions, Mao expressed gratitude for the Japanese invasion, asserting—I think correctly—that it had made his victory over Chiang Kai-shek possible. But in the 1980s academic historians began to accord the War greater attention and respect. Officials cautiously allowed their work to seep into the wider culture. Though it took several decades more, the sacrifices and achievements of the Nationalist troops came to be more fully acknowledged.

But with this new attention came a remarkable interpretation, in which resistance to the Japanese invasion was framed as a principal—as well as the first, and the longest—part of the worldwide war against fascism. In this view, it was not the naval and amphibious conflict in the Pacific but rather the land battles in China that constituted the most important theater and were essential to the eventual triumph over Japan. By its hard-won defeat of a wicked power, China—just like America—earned a moral stature that justifies its claim to leadership and its right to shape international institutions today. Japan by contrast was taken to be a threat to peace and deserving of little regional, much less global, influence.

Even more problematic than the Chinese version of this history, however, is the purpose it serves: to claim a moral foundation for the global power of the People’s Republic of China.

The view I have baldly summarized has been developed and propagated by the highest authorities, as Mitter recounts in nuanced detail. There have been signs of dissent about domestic aspects of the official story. Many Chinese have given more credit to the Nationalist government and especially to the Nationalist troops. Many are disposed to honor the citizens who endured hardship with Chiang in Chongqing (and not merely, as in the official story, those who were with Mao in Yan’an). A few even ponder the extent and the causes of Chinese collaboration with the invaders—generally a taboo topic. But on questions of international significance, Chinese are unanimous that the world ought to place their country’s contributions to the victory over Japan in the foreground of historical memory.

After rolling our eyes, we should acknowledge that Westerners underestimate the sacrifices the Chinese made to preserve their sovereignty in the face of what the Japanese Empire euphemistically called its Co-Prosperity Sphere. But the Chinese revisionist historical argument is not about the depth of suffering, but rather the military efficacy of China’s land war with Japan. Chinese believe their hardships bore fruit directly (at rare victories such as the battle of Taierzhuang) and indirectly (by tying down hundreds of thousands of enemy troops). Were these indeed essential factors in determining the war’s outcome? Such questions are fraught with uncertainty, but here there is reason to be skeptical. In the latter part of 1944, a daring Japanese offensive seized vital lines of communication, reconquered the rice-basket of Hunan, opened a supply route to Korea that ran all the way from Vietnam, and eliminated major American airbases. (This was Operation Ichi-Go, and one must wonder what would have happened in Europe if Germany’s Ardennes Offensive around the same time had been equally successful.) In short, the only thing that got the Japanese Army out of China was American atomic bombs. It’s obvious why that would be a bitter pill for the Chinese to swallow.

Even more problematic than the Chinese version of this history, however, is the purpose it serves: to claim a moral foundation for the global power of the People’s Republic of China.

The claim rests on an analogy: as America, victorious against fascism in the Second World War, came to shape and dominate postwar institutions, so China—victorious on land against fascism in Asia—earned a similar authority there. The title Dean Acheson gave his memoir, Present at the Creation, has become a mantra for internationally-minded Chinese. They point to their struggle against one of the Axis powers, their representation at the Cairo Conference, their stature as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council at its inception and say, in effect, “We, too, were present at the creation of the postwar world. The Cold War denied us a role in developing that world. Change is overdue. In the World War, China earned at least as much right to call the shots in Asia as America ever did.”

In Mitter’s reckoning, few but the Chinese themselves find this argument persuasive. It is indeed flawed.

First, it assumes that past victories in a good cause give hegemony a persuasive and lasting moral foundation. That didn’t work for Athens when it extorted money from the Delian league after repelling the Persians in 479 BCE, and it won’t work for Beijing. It wouldn’t have worked for America, either. The nations that accepted US hegemony for many years after the war did so not because they thought America had earned it, but because they judged it was in their own interest. Compared with historical empires, the US projection of influence was perceived as on balance benign and a source of prosperity, allowing smaller countries to economize greatly on defense. When citizens of what Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi called “small countries” weigh what Beijing’s dominance means for them, they pay less attention to the battles of the 1940s than to current encroachments in the South China Sea.

Second, it was the Nationalist government, rather than the Communist party-state which rules China today, that did most of the fighting in the War of Resistance. It was Chiang Kai-shek who represented China at the Cairo Conference, and it was his ambassador who took a chair at the newly-founded Security Council in 1946. It is curious for the Communist Party of China to claim as its inheritance the status earned by those whom it overthrew and repudiated. Mitter crisply observes that Beijing’s elision of the history implies that “the Nationalist state was legitimate and sovereign, presumably up to 1949, even though the civil war was based on the premise that it was not.”

Third, the discontinuity involves a long gap. The past can live when it is handed down, but not when it is exhumed. So much happened in the intervening decades, and the character of the actors changed. If China had acknowledged the Nationalist role all along; if, in reaction to Japan’s wartime atrocities, China had enshrined and protected human rights; if China had not literally fought a war against the United Nations, then perhaps a “Present at the Creation” case could be made. But an argument that requires forgetting so much appears to be an exercise in motivated mythmaking.

Few but Beijing’s partisans will find this mythology appealing, but Mitter’s scholarship clarifies its function. Public memory of the War serves less to illuminate the past than to relieve tensions in the present: a society marked by extreme inequality and consumerist anomie remembers wistfully a time of shared privation and sacrifice. Moreover, the focus on “Japanese devils” and their cruelty may be a necessary psychological displacement in a nation whose ruling party has killed millions of its own people.

Most of the war discourse has been top-down. For example in 2017, for purely political reasons and to the muffled dismay of Chinese historians, Xi Jinping decreed that curricula be changed nationwide to teach that the War of Resistance began in 1931 instead of in 1937. Between 1985 and 1991, the state built three large museums devoted to a propagandistic treatment of the war, and they have been repeatedly expanded and upgraded. But other thoughts and memories find a way to trickle up. In Sichuan, a private entrepreneur built several museums of his own. In some of the most suggestive and intriguing pages in this volume, Mitter explores how those private museums have used artifacts and veiled implications to question the official view of the past.

I dispute only two of Mitter’s points. First, he reports it as a fact and not merely a CPC tradition that American advisers tortured Communist prisoners at an interrogation center outside Chongqing during the war. Xujun Eberlein investigated this accusation in 2011 and disproved it.

Second, he blames Donald Trump, whom he harshly likens to Rodrigo Duterte and Recep Erdogan, for weakening America’s commitment to the postwar liberal order and thus easing the task of China’s diplomats. Mitter is not alone in this view. But how liberal, really—in the sense of “respecting and preserving liberty” —was the international order in 2016? Much had changed since 1945. The military-industrial complex that Eisenhower warned against in 1961 had 55 more years in which to grow. An American Secretary of State had asked a general, “What’s the point of having this superb military . . . if we can’t use it?” International flows of goods, money, and jobs had been restructured in ways that favored the elite classes of Western nations at the expense of their citizenry. America was far along in its devolution from a republic into Codevilla’s “classic oligarchy,” and the international order that Trump decried had come to reflect that transformation. Mitter rightly faults Chinese apologists for eliding history when they identify the regime of today with the regime of 1945. I fear that in his strictures against Trump for questioning such constructive arrangements as the Marshall plan, Mitter makes a similar mistake.

But my greatest disquiet while reading this thoughtful study was a sense that the background it examines and evaluates will soon feel like ancient history. For the last great war will be forgotten when the next one begins.