Colin Powell: Subordinate or Statesman?

It is good to be in the hands of a professional: Jeffrey Matthews of the University of Puget Sound offers a well-constructed, well-written, scholarly biography of his subject, Colin Powell, who was born in 1937 and has remained a popular public figure long after his retirement from government in 2005. The chronological narrative of Powell’s rise to four-star general and, eventually, the head of the State Department parallels American history and involvement in world affairs from the war in Vietnam through the Iraq War. Matthews is sympathetic to but never hagiographical about the first black American to serve as National Security Advisor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Secretary of State. This book should be assigned to undergraduate or graduate students of younger generations and also has much to teach general readers—regardless of field or profession—about U.S. military operations during the latter half of the Cold War and the Persian Gulf War, as well as the diplomatic highs and lows of the early years of the War on Terrorism. Colin Powell: Imperfect Patriot is always readable and, at many points, riveting.

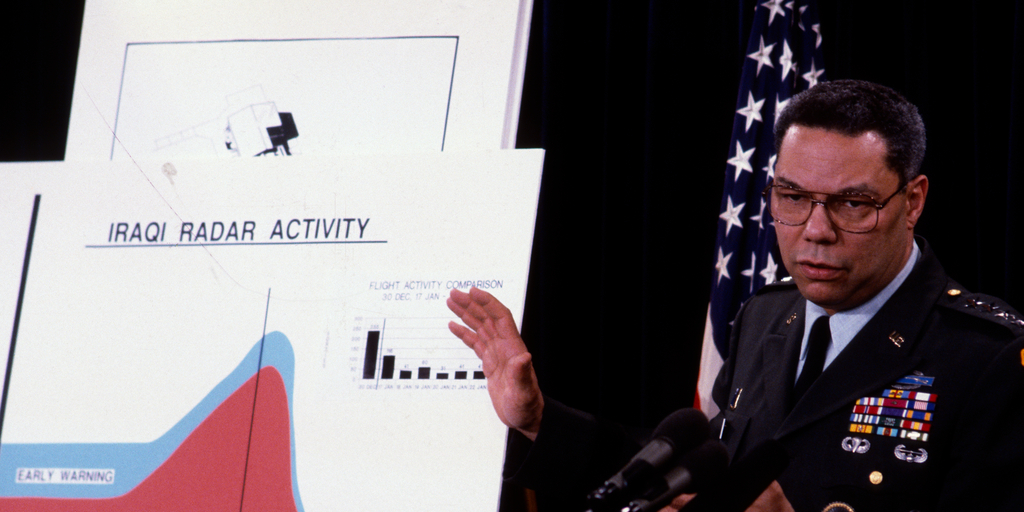

At the highest level, Matthews depicts the human condition in his study of Powell, who was full of both astute judgments and flawed assessments. Loyal, patriotic, and ambitious, Powell aimed to please his superiors out of honor and self-interest. In Powell’s relatively rapid ascent up the ranks of the U.S. Army, most superiors perceived him as top-notch in terms of leadership and organization, while some regarded him as better at carrying out than originating orders. Although he does not use such language, Matthews presents Powell as a tragic hero. Powell was both fortunate and brave as a tactical adviser and administrator during two tours in Vietnam, but unreflective about the 1968 My Lai massacre in an after-action investigation once described as a triumph of military paperwork. He was clear-eyed, honest, and capable as National Security Advisor to Ronald Reagan after the Iran-Contra scandal and as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for George H.W. Bush and briefly for Bill Clinton, yet he ultimately lost his way as Secretary of State in the Iraq War under George W. Bush. Powell later deemed his 2003 war speech at the United Nations a permanent “blot” upon his record of distinguished public service.

“An Exemplary Subordinate”

Matthews shows well that experience substantively shapes a person. What emerged in the Reagan years as the Powell Doctrine or Weinberger-Powell Doctrine—former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and Powell will be forever intertwined—was rooted in lessons from America’s failures in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, and the botched attempt to rescue 52 Americans who were taken hostage in Iran in 1979. The 1983 bombings of the U.S. embassy in Lebanon and a Marine barracks at the Beirut airport were additional devastating pieces of evidence. Like Weinberger, Powell’s main takeaway was that if military force had to be used, it must be applied in an overwhelming, targeted way to thwart the opponent’s effective response and to minimize losses. In this way, Powell and Weinberger contributed to Reagan’s successful efforts to help cure America of its Vietnam syndrome. Matthews also nicely captures Powell’s substantive impact on the Reagan-Bush era Base Force plan, which began implementation of the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act to reform and reorganize the Department of Defense for the first time since its creation by the 1947 National Security Act.

The author of several works on military leadership, Matthews takes Powell’s self-understanding seriously. Powell lived by his maxim, “leadership is all about followership,” and Matthews selects this famous quote as the epigraph for both the introduction and the epilogue. Matthews carefully traces Powell’s key professional character traits: loyalty, dependability, preparedness, competence, levelheadedness, integrity, and amicability. He emphasizes that, beyond high-level achievements in several presidential administrations, Powell spent more time overall in assistant positions to a superior at or near the top. This is all to support Matthews’ central thesis that Powell embodies the “exemplary subordinate.” Whereas combat is often the defining experience for military leaders, Powell’s self-described formative stages—each about a year in length when he was in his 30s—were professional, educational, and stateside. Powell identifies his participation in the White House Fellows program in the early 1970s as the “defining experience” of his career; he describes encountering Clausewitz at the National War College in the mid-1970s as “an awakening for me,” and Matthews adds that the War College’s curriculum in politics, history, military theory, and diplomacy broadened Powell’s perspective “on the place of military strategy within a political context.”

Characterizing his work as a professional biography, Matthews rightly includes a description of Powell’s parents, older sister, and generous mentors. Powell comes alive in these pages, as seen in the influence of his hard-working immigrant parents (and their emphasis on the importance of education), his happy and unstructured childhood in a racially diverse neighborhood in the South Bronx, and the discovery of his life’s purpose in ROTC at City College of New York in the mid-1950s. While advancing in the Army, Powell benefited from direct interventions by career guides such as Major General Henry “The Gunfighter” Emerson, Major General John A. Wickham, Jr., and Lieutenant General Julian W. Becton, Jr. If not for them and others, including Weinberger and Bush, Powell might have plateaued at the level of either Brigadier General or Lieutenant General. Oddly, Matthews fails to mention another essential influence: Powell’s wife, Alma. For Powell, part of “leadership is all about followership” means that his family, especially his wife, supported and enabled his successful career.

Matthews does not always elaborate on the tension arising from Powell’s attempt to be both a good leader and a good follower. He implies but never outright says that ultimately Powell may have been comfortable with his status as exalted follower. When exploring the Powellmania phenomenon in the 1990s, Matthews writes as if Powell had been selected by popular acclaim and turned down the presidency, rather than the reality: that Powell—who announced he was a Republican after retiring from the military and enjoyed remarkably high approval ratings for over a decade—chose not to run for and was never elected to any office. In some senses, Powell’s career is a story of what might have been. We are left wanting to know why.

A New George Marshall?

In the end, Matthews moves beyond followership and links Powell with “America’s most revered presidents, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Roosevelt” as fellow imperfect patriots. Indeed, everyone—great statesmen included—is fallible. But Matthews’ association should be to generals who also served in government. While a decent case can be made for comparing Dwight Eisenhower and Powell, the obvious juxtaposition is George Marshall and Powell. These consummate Army men excelled at key administrative positions, and each was widely esteemed in his time. Winston Churchill famously called Marshall the “organizer of victory” in World War II. Like Eisenhower, Marshall numbered among the elite super-rank of five-star generals. “Marshallmania” unquestionably dominated the 1940s and early 1950s. While FDR was president, then-Senator Harry Truman referred to Marshall as the “greatest living American.” Dean Acheson, Undersecretary of State to Marshall and his successor as Secretary of State, said of the general: “The title befitted him as though he had been baptized with it.” To the theoretical offer of trading one Marshall for 50 Douglas MacArthurs, Eisenhower privately commented, “My God! That would be a lousy deal.” At the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, when Marshall—unannounced—entered Westminster Abbey to find his seat, the whole congregation stood. Six months later, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the Marshall Plan.

Marshall had deeper, longer international experience in the Army than Powell, including four and a half years in the Philippines, two years serving in France during World War I (where he received high praise for planning American Expeditionary Forces campaigns), and three years in China in the 1920s. Powell’s tours in Vietnam, West Germany, and South Korea were brief by comparison. As Army Chief of Staff during World War II, Marshall also undertook extensive, extended travel, including to all the major wartime conferences and to Normandy.

And Marshall did not stop there. After World War II, he served in a number of capacities with mixed results (though more positive than negative). He was special presidential ambassador to China; Secretary of State during the critical time of the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and the beginnings of the North Atlantic Treaty; president of the American National Red Cross; and Secretary of Defense for a year during the Korean War. Marshall was fallible: He erred in equating the communists and the nationalists during the mission to China; by the standards of Truman, Admiral William Leahy, James Forrestal, and Acheson, he came late to understanding the nature of the Cold War; and he was incorrect in his stand against the creation of the state of Israel. Nevertheless, his service in World War II alone would assure his greatness. When one considers his term as Secretary of State on top of that, it becomes clear that he belongs in the pantheon of American statesmen.

Will Powell’s contributions to the Reagan and first Bush administrations, loyal service to presidents of both parties, and impressive professional accomplishments earn him a place in that pantheon? Still lacking history’s long view, it is too soon to say. Matthews’ dispassionate tone about Powell fades in the last section of the book, which focuses on the Iraq War. He strays from biographical analysis into Monday-morning quarterbacking from a comfortable armchair. But if we take Powell at his word about what he knew and said at the time, then he rejected thin single-sourcing and arguments without facts from others in the George W. Bush administration, and relied instead on seemingly verifiable facts and logical inferences. For many in both the Clinton and second Bush administrations, the question of going into Iraq to remove Saddam Hussein was a matter of when, not if, and broad bipartisan support followed Powell’s U.N. speech. With the information he had and the position he held, Powell can be judged accountable for an excessively narrow focus on weapons of mass destruction—which was his choice in terms of framing the argument—and for his ethically challenged response to the Abu Ghraib scandal, but not for the massive intelligence failure before the Iraq War or for the Department of Defense’s lapses in postwar planning.

From today’s vantage, though, it is unlikely that Powell will join Marshall—and Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt—in the company of America’s greatest statesmen.