Is Conservativism’s Future Strauss or Voegelin?

Glenn Ellmers is the Salvatori Research Fellow in the American Founding at the Claremont Institute, an influential conservative think tank in California. He believes that the United States is a post-constitutional nation and the cause of the loss of the people’s sovereignty is philosophical.

The Narrow Passage: Plato, Foucault, and the Possibility of Philosophy contends that we are willing dupes of a governing system in which “racism constitutes the original sin [and] science represents its Holy Writ and promise of salvation.” Far from living at liberty in a secular democracy based upon reasonable deliberation, the US today is a theological regime. We are willing dupes because we are philosophically muddled, with the worst of it that our leadership is lost inside a contradiction. Ellmers states, “The same ruling class that defends its authority on the basis of scientific expertise also insists on identity-based truth, such as Afrocentric calculus and feminist chemistry.”

Ellmers contends that Leo Strauss (1899–1973) is the best guide for today’s perplexed citizens, his Platonic political philosophy is the corrective for the philosophical drain on our sovereignty. Inspired by Socrates, Strauss can help conservatives reclaim liberty by returning to a political rationality purged of populist pressures. However, as Ellmers’s account unfolds, it seems a better guide would be Strauss’s contemporary and frequent correspondent, Eric Voegelin (1901–85). Ellmers’s argument suggests that conservatives might do better relying on Voegelin’s insight that law and liberty depend on symbols more than reason.

Our Predicament

Purporting to be “objectively rational, the rule of expert administrators is thought to transcend the old-fashioned need for the consent of the governed.” Despite the arrogance of contemporary power, we are heirs of the Enlightenment and programmed to defer to science and learning. There is a reason a successful presidential campaign had as its mantra, “Follow the Science!” Indeed, during Covid, “millions of the faithful observed Fauci’s commandments with pious devotion” and at times he seemed to be directing government more than the occupants of the White House. Born into a scientific civilization, we are expected to have data at our fingertips or to yield to those “who rely on empirical disciplines such as engineering, sociology, epidemiology, criminology, and economic modeling to justify their rational administration of society.” In short, and despite some bewilderment, we are primed to accede to the reign of the experts.

The irksome wrinkle is that our governing elites are the very same people who are “in thrall to an ideology of ethnic separatism,” spawn of the “dogmas of postmodernism” stemming from Nietzsche. The “objectively rational” that empowers our leadership is by them also denounced as “hegemonic, white, male constructs” of the will to power. Why do we consent to leadership that irrationally seesaws between hauteur and self-pity?

Ellmers argues that we are beholden to Plato’s idea that expert reason rules and, at the same time, seduced by Nietzsche’s idea of power. As postmodern people, we are savvy consumers of learning, but not the freer for it. Grimly, Ellmers believes, “our understanding of reality is manipulated to a far greater extent than was achieved by the former Soviet Union.” We pride ourselves on not being naïfs, but it is corrupting. Ellmers quotes Hannah Arendt’s 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism where she describes the mindset of populations inured to debunked official narratives: “Instead of deserting their leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.”

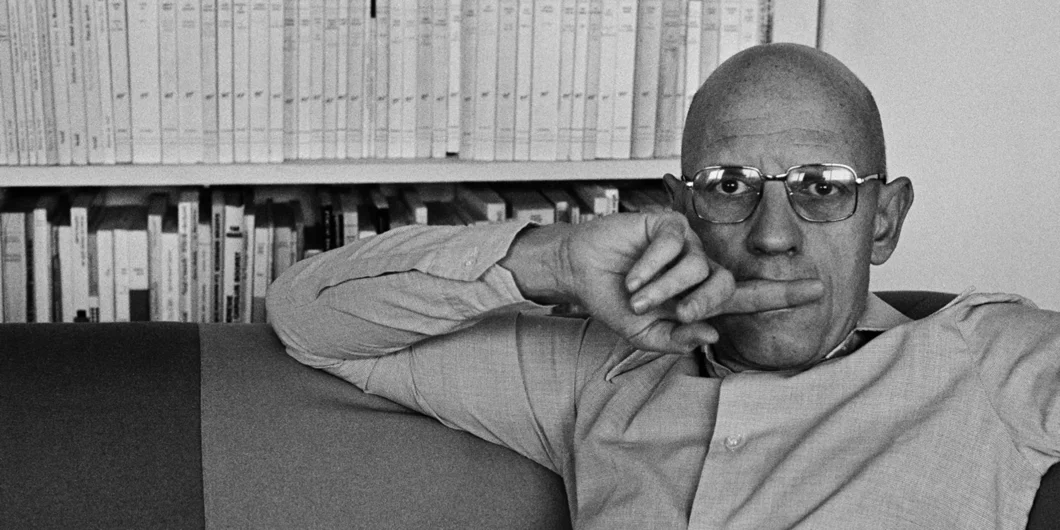

Though often bemused by the latest in political correctness, parents happily—indeed, rabidly—send their children to premier colleges where postmodernism is the stock-in-trade of the professoriate. Arch postmodern Michel Foucault explains what is afoot, as Ellmers recounts:

Foucault describes all those who accept the power dynamic as “willing subjects,” who are completely implicated in and even defined by the official discourse. Their identity and outlook are established by the power structure. For example, the status granted by certain credentials, such as an Ivy League degree, is inseparable from the regime’s overall legitimacy—which helps to explain how so many “respectable” people get coopted.

There is a narrow passage to democratic sovereignty because we are hemmed in on one side by our deference to expertise and on the other by our sophistication—a world-weary resignation to the ploys of power. Strauss, believes Ellmers, shines a light on the entrance to the passage.

Reason’s Natural Order

Ellmers explains that Plato’s Republic blessed the West with the idea that objective reason, and not tribal passion, is the source of legitimate government. This line of thought culminates in Hegel and his ideal of the liberal managerial state. Barely was the ink dry on Hegel’s works before Nietzsche cast suspicion that reason is only a subterfuge of the will to power. His brilliant prose culminates in Foucault and the postmodern theme of power/knowledge. Power/knowledge is the concept that reasoning is the obverse of domination. That is, there are no axioms or propositions that cannot be traced back to origins in political institutions, like, for example, the family. Think of the commonly accepted psychological idea that the endeavors of all of us are structured by the Oedipal Complex, that our strivings and speech are all downstream of the power our parents held over us when young. Contemporary politics lurches between Plato and Foucault.

The West has got itself into a pickle. Thankfully, the German émigré and long-serving professor at the University of Chicago, Leo Strauss delivers a solution. Strauss believed it was the job of philosophy to keep before the mind that the universe is an intelligible whole, that there is a rational natural order. Ellmers observes that we are “bombarded every day with official declarations of right and wrong” but the Straussian challenge is to use philosophy to interrogate accounts of justice to see if they are “rational, trans-historical, trans-cultural, and—it seems necessary to add today—trans-racial.” There is no rule of law without a proper philosophical accounting. Postmodern concepts like power/knowledge have begun to erode basic legal protections as these ideas demand “reform” of ancient guardrails like due process, rules of evidence, and the fairness of jury trials. Should philosophy fail in its task, the rule of law at the root of our freedom will not long remain, argues Ellmers.

Strauss is “the most formidable critic” of our age, contends Ellmers. Championing Socrates, Strauss argues that our governing conventions and mores must be interrogated by natural right, defined as “a rational inquiry into what is right by nature. Since all politics involves human beings, who share a common nature, knowledge of human nature and natural right is what makes political science transferable or universal.” This is the Plato of the Republic, “the world’s most famous work of philosophy,” a celebration of rational principle free of the machinations of power or the bias of popular passions.

Conservatives might want to put their theoretical resources into finding a symbol that secures the narrow passage to democratic sovereignty.

A sticking point is Plato’s final work, Laws. A Straussian conceit is to adopt the mantle of Socrates, to be a wry skeptic of prevailing political pieties, subjecting what is dearly held to rational scrutiny. This is only one part of Plato, however. Towards the end of his life, Plato penned his Laws, where he argued that rule of law is anchored in the cults, rites, and land appropriations of peoples and nations. Ellmers says, “We need to appreciate the moral-political integrity (and even the permanence) of the ‘closed city’ with its overwhelming sense of civic piety.” Do the geopolitical concerns of the Laws complement or conflict with the abstract Platonic Forms of the Republic? The Narrow Passage hesitates to answer.

In hesitation, there is consolation: “My hope is that recognizing and accepting our divisions as ancient and theological—and thus resistant to rational discourse—could soften some of the frustration and confusion.” I wonder whether Ellmers hesitates because he senses he may have backed away from Strauss into Voegelin. This may have happened because Ellmers does not just take postmodernism seriously, he is somewhat convinced.

Postmodernism

Foucault is not the bogeyman of the book, far from it. Ellmers celebrates Foucault’s expertise in the classics and thinks his treatment of power rich.

According to Foucault, power is the “substratum or ontological floor of human life,” and this seems right, concedes Ellmers, if nature is abolished and God murdered. Ellmers thinks conservatives can learn from Foucault’s subtle reflection on coercion. Biopower is a Foucauldian concept to explain that what we believe is free—our bodies and speech—are commandeered by power. What we hold dear suffer “coercive transpositions into discourse.” For example, a university or corporate culture is able “to produce different kinds of silence” or “different ways of not saying” things. To see Foucault’s point, consider only the biting of tongues in the workplace during the summer of George Floyd: “We are subjected to the production of truth through power … to produce the truth of power that our society demands. … We are constrained or condemned to confess.”

Despite its rich insights, postmodernism is no narrow passage. If power is the way of the world, tribal solidarity is our only safeguard. Strauss’s natural right is a principled way to mediate the passions, but it assumes a way back to aloof reason possible. Somewhat taken with postmodernism, it is not clear that Ellmers thinks this possibility remains open. In a footnote, we learn that neither piety nor truth is our fate, but irony: “Somewhere between Foucault’s rejection of reason and a complete science of the human things one might make the eccentric suggestion that the man’s place in the whole is not absurd, but it is ironic.” Ellmers seems to believe we are condemned to be savvy consumers of learning.

A Return to Symbols?

This slim volume is not only an unfinished work because of the hesitation at the heart of the book but also because its story moves along with the aid of long block quotes from others. They offer a platform in need of greater exploration. At around 80 pages, this physically small book is an extended essay of about 20,000 words. It is a quick, well-written read and its basic framing identifies a genuine problem. There are likely other core problems, besides. For example, nowhere is commerce mentioned, even though Foucault’s work on power is tied up with his Marxist inquiry into how commerce shaped sovereignty in the Enlightenment.

The Narrow Passage closes with a set of questions for the reader’s own reflections, e.g., can Americans better relate to history instead of iconoclasm? What role is there today for honorable ambition? Can religion revive and orient the nation again? Ellmers wonders whether we can find our way back to “the moral reality that is or ought to be evident to common sense.” These are worthy questions, but a longer work might have told us how Strauss answered them or perhaps called in assistance from someone like Thomas Reid, the great thinker of the Scottish Enlightenment who has most thought about common sense. Reid, who was both scientifically literate and a clergyman, could help Ellmers solve how best to think of the rightful place of science and whether the Bible can help us recover a “pre-scientific form of pious rootedness.”

Across the globe, cautions Ellmers, there is a “contemporary return to tribalism,” so we need to take seriously peoples’ “primal urge to believe and belong.” Peoples want, Ellmers believes, to experience “the inner order of the whole.” This is where Ellmers appears to back into Voegelin. There are resources in Plato’s Laws to think geopolitically about national belonging and self-understanding, but if Strauss thought along these lines, Ellmers does not tell us. For sure, Voegelin is excellent on this issue. His political theory delivers both the intelligible order of the whole and pious rootedness. Voegelin gives you both what Strauss offers and what Strauss struggled to deliver, apparently.

Voegelin argues that an enduring polity has a resilient symbol that opens space for both reason and passion. He gave this symbolic phenomenon the fancy name differentiation. A symbol worthy of humane politics delivers solidarity and facilitates persons differentiating themselves from the whole, able to frame theories, pursue interests, and indulge foibles. Symbols have “buy-in,” they express a people’s sense of cosmos which eliminates the irrational seesaw between hauteur and self-pity. Voegelin gives a nod to postmodernism by reexploring something the Enlightenment closed off, the value of myth.

In The Ecumenic Age, Voegelin wrote, “No more than the cosmos, I had to conclude therefore, will the cosmogonic myth disappear. Any attempt to overcome, or dispose of, the myth is suspect as a magic operation, motivated by an apocalyptic desire to destroy the cosmos itself.” Voegelin’s political thinking examines the symbols that document how peoples have thought about their place in world order and history.

Intriguingly, America’s leading geopolitical thinker, Robert Kaplan, has recently suggested Venice with its annual ritual of marriage to the sea might be a symbol for us. He believes we are living at the eventide of the Enlightenment state. Unified nation-states are being eclipsed by neo-medievalism, a return to harlequin principalities, enclaves, and powerful family sovereignties. The antique city-state of Venice, with its high civilization defended by diplomatic, military, and commercial nous, is a symbol of governance well-suited to our times. Situated in the political cauldron of the Adriatic, the rites of Venice sustained a republic for a thousand years. Obviously, adaptations would be necessary, but the republic endured because it navigated with aplomb the tension between elite acumen and its religious and civic vernacular. Money-making, music, rituals, and the arts all had a place, and with the likes of Paul of Venice, Christine de Pizan, and Helen Cornaro, Venice had philosophers, too.

Conservatives might want to put their theoretical resources into finding a symbol that secures the narrow passage to democratic sovereignty. As even Plato taught, reason is not the only tool in the shed of conservative governance.