The ancients show us that when mutual agreement on the meaning of concepts like liberty starts to break down, there will likely be conflict.

Rome Without Greatness

An interesting, little-noted truth about our time is that many celebrated historians are often mediocre minds and rarely good writers. Yet they produce increasingly labored and researched tomes of thousands of pages, at the end of which, the reader’s judgment has been bored or exhausted, but not necessarily educated. We have bestsellers and prizewinners, but our obsession with facts has not produced a rival to the last great historian, Churchill. We have only hobbyists who fail to grasp greatness.

History was of greater interest in the 18th and 19th centuries, when men who were thought to possess great minds attempted to prove whether modernity was greater than antiquity, or to settle the question of Progress. Nowadays, those questions aren’t even raised. We have everything from archival and archaeological work to historical romances, but our mediocrity is ever-worse, ever less-polished, and our few good historians are not even taken seriously.

Our elites, being Progressive fanatics, expend no great effort of thought or art concerning a past they believe has nothing fundamental to teach them. Accordingly, modern historians—generally academics—often study economic, social, and cultural forces, which tend to present humanity in a mold of mediocrity. But classic historians studied the subject that fascinates us—greatness—the politicians who made war and peace. So we are split between popular fascination with antiquity, Rome, and above all Caesar, and elite denial that greatness is real.

The Romance Of Mediocrity

This spiritual division is resolved by vulgar TV shows reducing antiquity to orgies and violence (think Starz’s Spartacus) and volumes of gossip recycled from ancient sources. This misfortune is a necessary rearguard action on behalf of Progress—the popular fascination with the great men of the past is aroused, then disappointed by crass minds. The worse the author’s judgment, the more debased his taste, the more inclined he is to persuade his audience that antiquity was merely decadent and worthless.

Thus does Peter Stothard, former editor of The Times and then The Times Literary Supplement, in his third (mostly fictional) account of Roman history, The Last Assassin: The Hunt For The Killers Of Julius Caesar. He previously dealt with Spartacus and Cleopatra. Stothard is typical of a bored age whose elites have little interest in—or perhaps, a strained capacity for—contemplation and therefore no awareness of greatness, but flatter the popular taste for gossip, itself a more authentic remnant of that awareness.

Of Stothard we may say he achieves a kind of aesthetic unity, since his prose is as terrible as his characterization, and in the same way. This is his idea of wit: “The man who had rolled the dice to cross the Rubicon controlled everyone’s luck.”

Every page is littered with aborted thoughts and speculations as to what might have gone through the minds of Caesar’s assassins, the Liberatores, starting before the Ides of March and ending with their deaths. He never, even by chance, offers a coherent portrait of any of these men. One does soon conclude, however, that they must all have been inferior to Stothard, who treats them with an unusual form of contempt. He doesn’t disapprove of them on moral or political grounds—he seems to disapprove, instead, of any interest in them. He is at work to prove they’re not special and do not deserve the attention he gives them, as though his audience forced the subject on him. None of the world-famous men in the story is treated with admiration—none of them is allowed any nobility, but all are constantly reduced to the pettiest concerns you can imagine.

One may therefore say that the moral purpose of this style of writing which mixes sensationalism with boredom is to edify us through mediocrity—to teach us that the only truly foolish thing a human being does is admire another human being. Perhaps middle-aged readers of a certain class need the reassurance that they’re not inadequate and, indeed, no worse than the great personages of old-fashioned history books.

Apolitical Contempt

So if you ever thought maybe Brutus was noble or Cassius clever, if you ever thought Antony was a man in the heroic mold, get ready for what you might call the Game Of Thrones theory of history: all human things are trashy, corrupt, and petty. Stothard avoids orgies, perhaps because he prefers reducing great historical trials to newspaper gossip, a creature of the age of silly journalists manipulated by leaks from anonymous official sources. Stothard doesn’t offer analysis of the major battles or political conflicts or the men involved. His narrative is mostly idle speculation, largely without documentary basis, but also without an elaboration of character—in short, he behaves as journalists do covering politics nowadays. You don’t end up knowing what kind of men Brutus, Cassius, Caesar, Antony, or Octavian were.

Perhaps writing has degenerated because we don’t have new things to say, yet must find novelties to amuse ourselves. Thus, Stothard makes a half-hearted attempt to show the conspiracy through the eyes of a man about whom we know next to nothing: Cassius of Parma, a relative of the famous Cassius. This choice would have been better suited for a novel, had Stothard the talent or the art for that form.

The history of Rome’s loss of freedom has long been the education of elites—indeed, of anyone interested in the character of politics.

He avoids characterizing his protagonist, so we neither can nor want to see the end of the Republic through his eyes. Stothard just drops awkward references to the city of Parma to remind us of Cassius and mentions his few extant letters. He doesn’t care about Rome’s civil wars—he mostly talks about how different characters feel about the events, as though his suppositions about their moods mattered more than the deeds we already know from historical accounts–nor has he mastered the intrigue that stretched from gangs of brawlers and slave gladiators all the way to the great Cicero, himself treated contemptuously as an irresolute sophist.

Nor, on the other hand, do we learn of Caesar’s greatness from his ability to keep a hold of the imperial city that unraveled without him—until, that is, Octavian enslaved it. It’s strange that a story about his assassins should not care much either about the man himself or the city that made him great, but perhaps that’s an acknowledgment of what cannot be reduced to mediocrity—politics, which Stothard treats with contempt.

The Great And Terrible Caesar

People interested in Caesar and Rome, however, deserve much better than this. And perhaps if we added seriousness to our fascination, our very desire for novelty would lead us back to the fundamentals of politics, since so much dross now clutters our thinking. It may seem an accident, but it’s the main advantage we have over previous ages—learning is an exciting adventure now, humanity a treasure to discover, buried under Progressive prejudices.

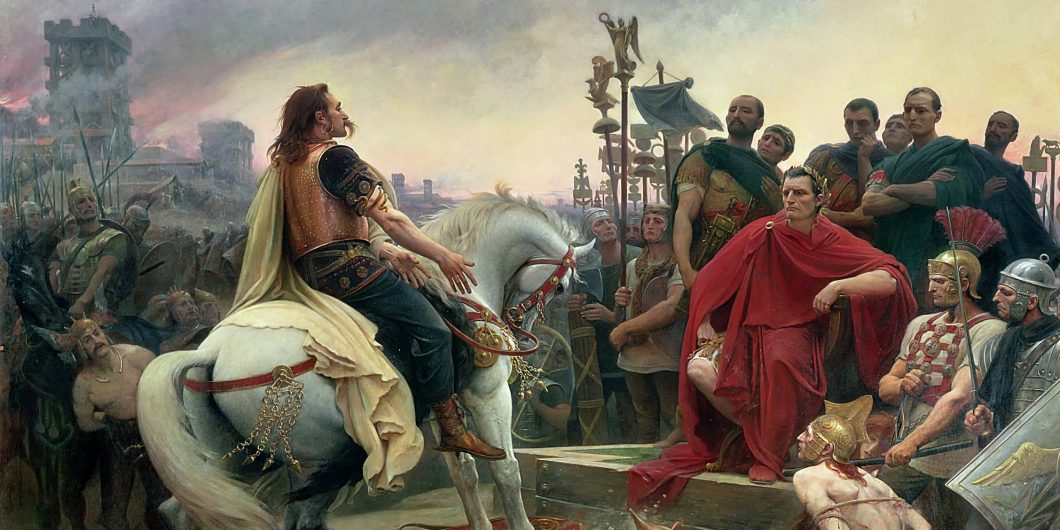

Rome’s fame has lasted in citizenship, republicanism, and even architecture because it shows us the full tragedy of politics. The greatest man the city created, by his greatest victories, destroyed the very freedom that made the city what it was. Born a citizen among citizens, he made himself a master of slaves. We see clearly here the dialectic of freedom and empire and can therefore learn what human nature and circumstances allow, what prudence advises.

Caesar’s greatness was the consequence of political decadence. The civil wars before his time as much as those he fought and those fought in his name revealed and advanced republican collapse. Political moderation, of whom we may say Cicero was the last hero, was becoming impossible. But of course, we cannot understand decadence on its own terms, without reference to nobility and justice, any more than we can understand disease without reference to health.

The killing of fellow citizens proved impossible to stop, not only because it violated fellowship, but because it violated citizenship. Concern for justice had ceased before the blows were struck. Romans did to each other what they had long done to enemies or slave populations, because they had begun to educate each other to do such things for praise and rewards. Peace turned to civil war because education for war, an impious manliness, was too successful.

We look at the end of the Republic, the beginning of Empire to understand our own nature. Strangely, the greatness of the city was not compatible with such a great man. Caesar was a creature of luxury, as much defined by hubris as by madness. Caesar competed, as all Roman citizens, for honors, but he won and thereby ended a competition believed to recur perpetually. What was believed to ennoble all free men made them all slaves and revealed imprudence—once the ambitious lost sight of the goods that victory made possible, only victory itself remained, which proved to destroy itself, liberty, and self-respect.

The enemies of republican government prevailed in Rome. This does not prove their prudence, even in the most vulgar way, since we see how they ended up. Nor is replacing freedom with despotism obviously good or admirable, given the cruelty and stupidity it often evinces. But friends of freedom must learn from civil war if they are to understand how hard it is to prevent a political collapse into tyranny. Our histories should teach this, yet no one is doing it.

Powerlessness

The ugly mediocrity of our times is obvious in history above all, because in past ages historians cared very much about nobility. Each great writer asked himself why his work was necessary and how it was possible to accomplish the task of ascending by art to nature. Each had to deal with terrible events and figure out what it means to be human in the face of such suffering and failure.

Nowadays, people cannot imagine the end of the world. Extermination fantasies proliferate, but not visions of another way of life. In the past, though, there were other ways of life, other beliefs, and those people who molded them were human, more or less as we are. It is urgently necessary to learn how to deal with our prejudices and confront our situation, since we are no longer happy with the prejudices of Progress and we have learned to fear that perhaps our political freedom is in danger. Our politics is ever more full of strife, ever less civil, and yet we do not take seriously the most famous history of republican collapse.

Rome was a world that ended in a way we cannot fail to attend to, with a great man destroying it. Only the Greek cities’ loss of freedom is better attested by great historians. These histories have long been the education of elites—indeed, of anyone interested in the character of politics. It was once thought that facing up to our powers and their limits would make us less deluded.

Rome and Caesar are unknown to modern elites, because they refuse to believe in the existence of great men. The sophisticated prefer to believe themselves powerless so long as it allows them to think everyone else is, too. This is what trashy histories teach—that men are playthings of a cruel fate that happily has spared the degenerate historians, but perhaps not for long. Behind their cynicism, there is despair, and an end of man.

Our elites always teach the same history: they alone are authorities on what is possible and good for human beings. Nobody who doubted the prejudices of silly Progressives is worth taking seriously. The past, the more so the more we care about it, is a catastrophe, redeemed only by our escaping it. This is a teaching of hopelessness we must escape if we are to restore moderation and justice among ourselves.