A proper understanding of the Fourth Amendment can accommodate modern technology, even though that technology was not known at the time.

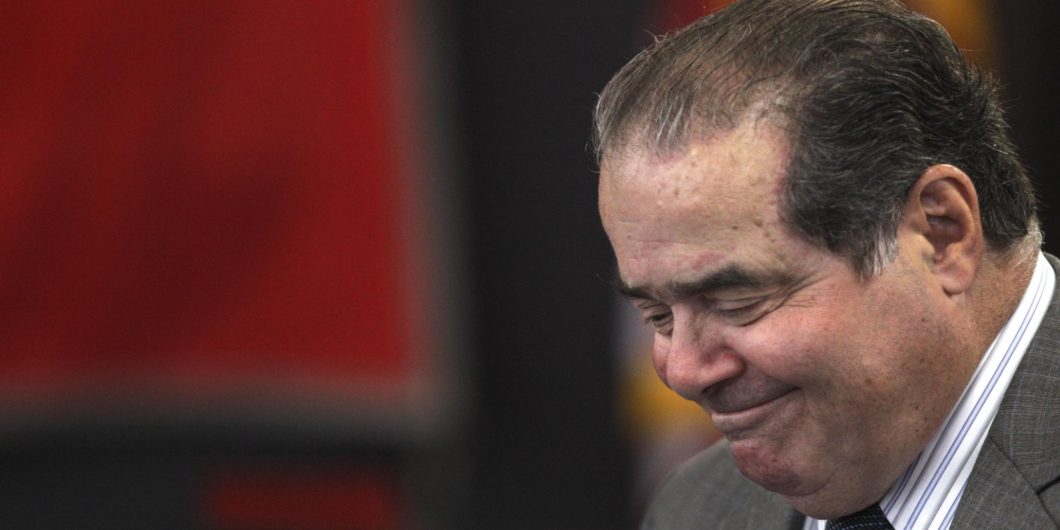

Scalia's Wisdom and Wit

The British have a saying that a great politician makes the weather. The rest must figure out how to deal with the new patterns of social disturbance that this statesman or stateswoman creates. Antonin Scalia was the justice who created the jurisprudential weather for our time. Judges and academics still react to his ideas.

Thus, it is a fitting tribute to the justice that The Essential Scalia: On the Constitution, the Courts, and the Rule of Law has been published four years after his death. As important as Supreme Court justices are when they render decisions, their essays and opinions are rarely worth studying as an oeuvre once they have departed. But The Essential Scalia is, indeed, still essential for anyone who studies law, as his ideas still drive the debate.

The editors, Jeffrey Sutton, a judge on the Sixth Circuit, and Edward Whelan, the President of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, wisely begin the collection with the justice’s essays on his great passions: the centrality of rules to the law, originalism, and textualism. The three ideas are interrelated. For Scalia, originalism and textualism both seek the public meaning of the words of an enactment—of the Constitution and of statutes respectively. Scalia also contends that originalism is justified normatively in large part because following original meaning generates rules that discipline interpreters and prevent them from exercising their personal discretion. As the title of the first essay in the collection shows, Scalia believes that the essence of the rule of law is that it is a law of rules.

The editors then provide excerpts from many of Scalia’s greatest opinions and essays on more specific topics, allowing us to watch how his theory of law is translated into action. In his constitutional law dissents, Scalia consistently complains that the majority has not created a rule, making the foundation of government uncertain. For instance, in his celebrated dissent in Morrison v. Olson, he observed that the majority had deprived the president of uniform control over all executive branch subordinates. Yet it had failed to specify any clear test for determining how much of executive power Congress can make independent of the president, leaving it wholly uncertain just how many government officials the legislature could turn into free-floating bureaucrats.

Scalia also defends the famous case of Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council because it creates a rule that tells judges when to defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute: whenever it is ambiguous. Scalia finds this rule, even if imperfect, much superior to “th’ol’ totality of circumstances test” it replaced. That standard instructed courts to defer based on a wide variety of factors, including the age of the rule and their assessment of the expertise of the agency. But no less a source than Justice Samuel Alito reported that Justice Scalia became concerned in later years that agencies were exploiting Chevron to undermine Congress’s lawmaking authority, blurring an even more important rule: the distinction between law and administration.

Thus, considering Scalia’s application of his seminal ideas also helps us recognize that, like all important concepts, they have some internal tensions and leave room for development to resolve them. For another example, in Employment Division v. Smith, excerpted in the book, Scalia held that the Free Exercise Clause did not allow a citizen to avoid complying with a neutral law, no matter how great the burdens imposed on his religious activity by that law may be. Scalia reasoned that this interpretation of the First Amendment gains support from its being a rule. An interpretation that permitted the Free Exercise Clause to trump such a law would require the judiciary to weigh the burden on religious exercise versus the need for the law.

But many scholars of the First Amendment, most notably Michael McConnell, have argued that the original meaning of the Free Exercise Clause required such weighing. More generally, it suggests that even if following the text of the Constitution generally creates clearer rules than other interpretive methods, it does not necessarily follow that it will do so in every case. The generally rule-like nature of texts may offer a justification for originalism, but it does not provide a skeleton key for unlocking the original meaning of every clause.

Beyond its theoretical interest, The Essential Scalia is great fun because Scalia was undoubtedly the wittiest Supreme Court justice in history.

Scalia’s decisions also show that the methods used to discover original meaning remain subject to debate. One of Scalia’s frequent arguments against interpreting a clause of the Constitution in a particular way is that no one at the time thought it would be so interpreted. Thus Scalia says “that there is no doubt that at the time [the First Amendment] was adopted in 1791 no one thought that this provision invalidated laws against libel—which existed then and have continued to exist ever since.” Thus, for Scalia, New York Times v. Sullivan, which held that the First Amendment sharply limited the scope of libel law against public figures, was wrongly decided.

But many if not most originalists today oppose using the expected applications of a provision by those who lived close to the time of its enactment to limit the meaning that a clause will bear. I am, however, somewhat sympathetic to Scalia’s position. While expected applications do not constitute the meaning of a clause, they are often relevant evidence of the meaning. Language, particularly in morality and politics, is often slippery and cannot be understood without context, which expected applications can help supply. Nevertheless, the role of expected applications is an issue that requires far more attention than Scalia gave it.

Scalia sometimes said that the meaning of the Constitution is its ordinary meaning. But here the law in action, as represented by his opinions, belies his sweeping claim. For instance, in Crawford v. Washington, also excerpted in the book, Scalia understands the meaning of the Confrontation Clause against the common law background which gave rise to it—something that would not have been available to the lay reader of the Constitution. The Constitution was not created ex nihilo but against the Anglo-American law that came before it. That law, including its rules of legal interpretation, is not less relevant to contested meaning than are expected applications. Indeed, the legal context is probably more relevant because the expected applications of different Framers may be more likely to conflict than the legal background which judges worked to make coherent.

But it is not to criticize Scalia to acknowledge that some of his claims present more complications than he worked out. Scalia put originalism back into constitutional law at time when it was slighted much to our detriment. Like Robert Bork, he offered the first map of a new world, or perhaps more accurately, rediscovered an old map of the world that had been forgotten. But law, like all great enterprises, is fractal. The early maps need to be filled and boundaries clarified. Those who do this necessary, more technical but less innovative work, owe a great debt to the original modern originalists like Scalia.

Beyond its theoretical interest, The Essential Scalia is great fun because Scalia was undoubtedly the wittiest Supreme Court justice in history. So many pages crackle with jokes and humorous sallies that it is difficult to single out any of them. But for providing sustained jollity that will stay with you throughout the day, I commend “What is Golf—PGA Tour v. Martin.” In that case, the majority held that the Americans With Disabilities Act required the Professional Golfers Association to permit a golfer who had trouble walking to dispense with the association’s rule that competitors could not use golf carts. Scalia wrote a marvelous dissent, ridiculing the idea that justices could determine the essence of golf. It ranks not with the work of Oliver Wendell Holmes or John Marshall but with that of James Thurber or S.J. Perelman: “If one assumes, however, that the PGA Tour has some legal obligation to play classic, Platonic golf. . . . then we Justices must confront an awesome responsibility. It has been rendered the solemn duty of the Supreme Court of the United States to decide . . . . What is Golf.” Scalia then showed great verbal virtuosity in mocking the answers that his colleagues proposed.

This relatively short book is indeed essential reading for any student who wants to practice law. It shows how to muster facts and logic, all in the service of persuasive argument. It moves easily from the abstract to the concrete, from complexity to pith. It is a primer in legal writing—clear, pointed, and free of jargon.

My only criticism of the book is that it leaves out some of Scalia’s excellent writing, particularly on economic matters. He was editor of Regulation at a time when the need for deregulation was just being felt, and he wrote some excellent essays for the magazine. On the Court, he issued some wonderful opinions extolling the free market. Particularly notable is his majority opinion in Verizon Communications v. Trinko, where he celebrates the desire for monopoly as a dynamo of progress and productivity.

Scalia was not just a great jurisprude but a classical liberal in full. Perhaps we need a sequel.