Surviving Hyperculture

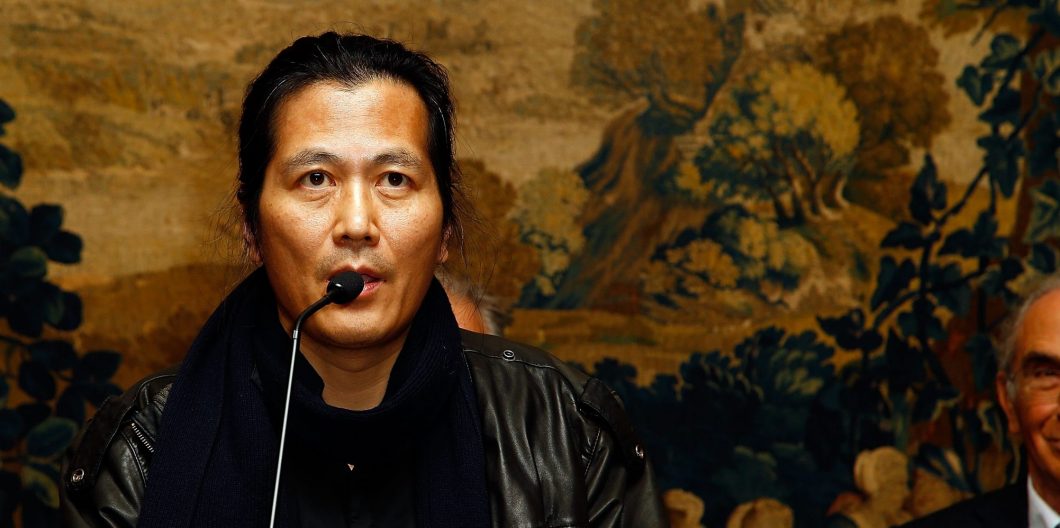

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han is known for his treatise-like reflections on modern life. Combining philosophical inquiry with cultural critique, Han objectively delineates and clarifies modern society’s existential ailments, while trying to discern where we may be going on the current trajectory. His book Hyperculture: Culture and Globalization is a look at the way the world is shifting due to globalization. Han wonders whether the term “culture” even means anything anymore, given human society’s turn away from national and ethnic particularity into a more fluid world of never-ending change.

The Meaning of Home

By nature, man is restless. We want to explore the worlds we haven’t experienced yet. Some are more courageous than others but deep down, many people have what is known as wanderlust. This desire to wander can be both a blessing and a curse. It can often mean more freedom, something man is obsessed with. But that desire to endlessly explore also gives us an awareness of the existence of home. Given a choice between those two options what we would rather do—travel or stay at home—we may often find ourselves conflicted.

Wanderlust shows that we wish to experience something that is alien or foreign to us. On the other hand, there are some for whom, as Han writes, “Happiness is conceived as a phenomenon associated with the family, the homeland and household.” Both orientations may be good in different ways. But what happens when identity begins to dissipate, and we are faced with neither a homebound provincial nor a restless cosmopolitan? Are we mere tourists, to use Han’s metaphor, or are we searching for a deeper meaning? By definition, a tourist collects experiences that are often superficial, and the way we experience culture today seems to operate on the same level.

Although Han doesn’t mention the specific phenomenon of acedia, it is precisely this existential restlessness, or spiritual sloth, that has overwhelmed society.

Han is concerned with the same question. “Are we approaching a culture,” he writes, “that has become a boundless, even site-less, hypercultural-acoustic space in which the most diverse sounds are jammed together side by side? The hypercultural condition of the ‘side by side,’ of simultaneity and of the ‘as well as,’ would change the topology of happiness.” Rootlessness to such an extreme can lead to a total existential breakdown. Any notion of boundaries, be they metaphysical or geographical, will quickly dissipate and with that the perennial question of what it means to be human. After all, it is our differences that maintain creativity as well as, unfortunately, destruction.

The worlds are shifting, and the question is whether a new world is emerging. “After the end of culture,” writes Han, “should the new human being simply be called ‘tourist’? Or are we at long last living in a culture that affords us the freedom to spread into the wide open world? If we are, how might we describe this new culture?” Han is alluding to the “end of culture,” which is enough to make everyone quite depressed. Fast-moving technology has precipitated this change, and we cannot turn back the clock. Technology has tapped into human listlessness and spiritual torpor, taking many souls hostage.

Although Han doesn’t mention the specific phenomenon of acedia, it is precisely this existential restlessness, or spiritual sloth, that has overwhelmed society. This collective experience of disconnectedness (even as the whole world is apparently right at our fingertips) has been pervasive, and is yet another sign that we’ve lost our stability, or in Han’s words, our “home.”

Culture Wars

Han’s concept of “hyperculture” is drawn from Ted Nelson’s invention of hypertext. Han explains that, for Nelson, everything is connected, and hypertext is not necessarily limited to digital text. As Han writes, “Neither body nor thinking follows a linear pattern. … [H]ypertext promises a liberation from compulsion, [and] what Nelson imagines is a hypertextual universe, a network without centre, in which everything is wedded together.”

Han is essentially describing Google. One of Google’s ambitions is to contain an entire library of everything in one place, with no regard for categorization. This sounds like hell on earth, a place that is not a place, and that has no time, no embodiment, and most of all, no definition. This entire project is antithetical not only to Western thought but also Islamic and Eastern thought—all traditions which thrive (in different ways) by defining who we are as human beings and how we relate to God, each other, and even inanimate objects.

If we have reached the point in our society in which everything is connected in a way that renders us even more alienated from that very society, then we have to ask: what is culture in this context? What is humanity? Do such things even exist anymore? In the United States, for example, we like to speak of the so-called “culture wars,” which indeed are not imaginary, and they have serious consequences on different aspects of society. But given the all-pervasive reality of globalization, are we engaging in culture wars anymore, or are our battles shapeshifting, unable to be captured and properly dealt with?

Han writes, “A war of cultures? A hyperculture without centre, without a God, without sites will continue to trigger resistance. There are many for whom it means the trauma of loss. … Will those ‘ancestral voices’ prophesying disaster be proved right? Or are they just the voices of a few revenants who will soon drift away?”

Even the days of Oprahesque “finding yourself” are gone now. Now, nothing is found; we just go on looking.

These are valid questions. We are faced with the task and the specter of the globalized internet, and we’re still not entirely certain how to relate to this monster. In many ways, we are still dealing with David Bowie’s description of the internet, given in a 1999 interview with Jeremy Paxman: “[The internet] shows us that we’re living in total fragmentation. … I don’t think we’ve even seen the tip of the iceberg. I think the potential [of the internet] is unimaginable. … It’s an alien life form.” For Bowie, the internet has made possible the “duplicity” of being, something which we certainly are seeing quite a lot right now. If an individual is duplicitous because of the availability of digital avatars, then how can we expect to build a cohesive or defined community?

This is also Han’s implicit question. This constant digitization of life has been changing the collective consciousness, and this is something we have to confront directly. Even something as fundamental as love can get lost in the world that promises “the future [that] is ‘everywhere’ that I ‘turn to’.”

There is No App for That

Throughout his book, Han focuses on the notion of “de-site”: an idea that everything is becoming rootless and that we are as a result unable to define different aspects of life. Using the slogans of different companies, such as Microsoft (“Where do you want to go today?”) and Linux (“Where do you want to go tomorrow?”), Han explains that these developments have created a “seismic shift … the end of specific Here.”

This is also reflected in advertisements for Google, iPhone, and similar products in the mid-2000s, depicting people mindlessly and flatly singing “I don’t know what I’m looking for but I’m going to look some more,” or the more famous, “There’s an app for that.” What indeed are we looking for? Even the days of Oprahesque “finding yourself” are gone now. Now, nothing is found; we just go on looking. People are using apps that truly have no meaning or use other than to help us lose ourselves in the digital labyrinth. We collect everything and nothing: people and objects are present to us in some sense, yet nothing is embodied.

Imaginatively, Han uses an example of William Randolph Hearst’s “Xanadu-like castle” as the prime example of “hyperreality,” and “sitelessness.” Han writes, “Cultural goods from all the world, of all ages, styles and traditions, are condensed into a side-by-side. Forgeries seamlessly combine with genuine articles, thus sublating fake and genuine into a third category of Being, into hyperreality.”

The difference between one thing and the other becomes meaningless because they exist simultaneously. It’s hard to tell the difference between the real and the fake. We are called to this task every day if we engage in the digital world. The path is always the same, yet unlike the simple labor of repetitive daily chores, there is hardly any meaning attached to it. Our only embodied interaction with the internet is the touch of the screens or the computer keys. But even here, we see the difference: the touch of the iPhone is just as disembodied as the experience of the internet. The physical “feedback” we’re getting is barely felt and certainly not heard (unless you engage in yet another simulation by turning on the sound that rather poorly mimics the touch of the keys).

Pilgrims or Tourists?

Although Han’s overuse of Heideggerian language sometimes gets in the way of the subject matter itself, his arguments do reveal themselves. Since he is concerned with “sitelessness” and “rootlessness,” Han looks at the notion of pilgrimage. Sacred language has all but disappeared from our existential and literal vocabulary (at least from the collective myriad of voices), and the concept of a pilgrim seems antiquated. But in fact, this may be one of the primary ways to return to God.

It is true that pilgrims are always on a journey, and in this sense they are rootless. But their souls and hearts are at peace because they are resting in God’s hands, so to speak. A pilgrim encounters troubles and difficulties all the time, but he or she must persist in the journey through faith in God. Han accepts that a pilgrim does not feel fully “at home” or “Here.” But he does have a mission.

A pilgrim is not a modern human being at all. As Han writes, “A pilgrim is a peregrinus. He or she is not fully at home Here, and thus pilgrims are on their way to a special There. Modernity overcomes precisely this asymmetry between Here and There. … [I]nstead of being on its way towards a There, modernity progresses towards a better Here. But a necessary part of the pilgrim’s wandering across the desert is uncertainty and insecurity, that is, the possibility of going astray. Modernity, by contrast, thinks that it is moving along a straight road.”

A pilgrim is geared toward arrival, whereas modern or postmodern man (especially one whose existence is defined by globalization and digitization) couldn’t care less about that. Since everything is shapeshifting all the time, today’s digitized human being quickly losing his or her humanity through such an endeavor.

A pilgrim also accepts the reality of uncertainty, knowing that the only thing he or she has to rely on is God. A pilgrim takes a chance, a great risk that is often met with tragedy or simply an end that was not imagined. But the honesty and authenticity of the pilgrim’s existence sets him apart from today’s purposeless shapeshifters. In Han’s words, we need to “re-theologize” life.

“In the hypercultural space,” Han tells us, “one does not ‘hike’; one ‘browses’ what is presently available.” There is no point of departure or arrival, and this will prove to be an existence devoid of meaning. If we look at ourselves as pilgrims, then we can also conclude that we desire belonging. This is one human desire that rarely goes away. But a “tourist” (to use Han’s word), or someone who is searching for nothing, will never care about belonging. As Václav Havel wrote, “The tragedy of modern man is not that he knows less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothers him less and less.”

Is there an exit from “hyperculture”? Han doesn’t really offer any answers. He should not be faulted for this, since he generally engages in distanced philosophical analysis of contemporary problems and phenomena. But this is also the weakness of the book. Although Han offers an excellent analysis of the problem of technology, readers may crave more ethical analysis. Han is essentially a phenomenologist, and thus less concerned with moral philosophy; however, the battles we’re entwined in do require some ethical reflection. Han’s book is certainly a good starting point for moral analysis of today’s cultural problems.