Two problems—war and kingship—should guide the viewer revisiting Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films twenty years later.

Tolkien Among the Greeks

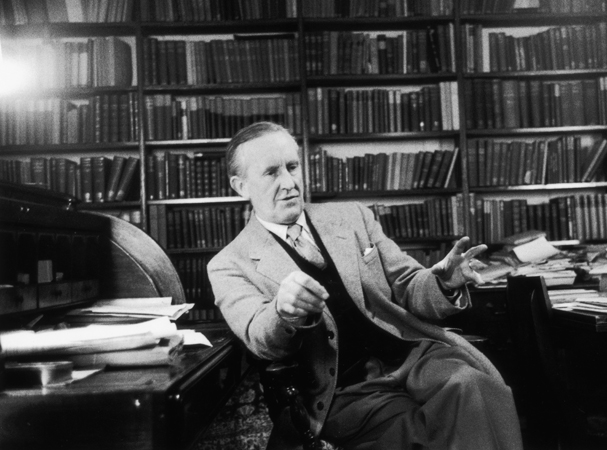

It is not too strong to say that the writings of Oxford don, J. R. R. Tolkien, are a pillar of our collective psyche. But for Tolkien, there is no Harry Potter or Game of Thrones. Official Ukrainian government communiques routinely talk of stopping incursions by Orc squads, and Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister, regularly quotes Tolkien in her speeches. In the battle of memes, that other tremendously influential fiction, James Bond, is bested by Gollum and Gandalf.

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Utopianism and the Classics expands how we think about Tolkien. It is part of a wave in Tolkien scholarship correcting the long-held focus on the medieval, Nordic Tolkien. Tolkien’s professional life centered on medieval English literature and one of the first reviewers of The Lord of the Rings described it magnificently as the last great medieval epic. Undoubtedly, an Anglo-Saxon and knight-errant mood characterizes his writing, but the legendarium scholars now contend has much to do with his interest in modern books. Tolkien was by no means rigidly anti-modernist. He loved typewriters and cars and was—like his contemporary and fellow veteran of WWI, Ludwig Wittgenstein—an avid reader of crime fiction, with an appreciation of science fiction, too.

Hamish Williams wants to supplement the fresh focus on Tolkien and the moderns with a nod to Tolkien and the ancients. His volume balances the mood of the Germanic, beer-swilling rugged climes of the North in Tolkien with the warmth of the sun-soaked civilization of the South. He points to a Tolkien letter where the capital of Gondor, Minas Tirith, is imagined on a latitude with Florence, the Númenórean port city of Pelargir on a latitude with ancient Troy, and Aragorn’s revival of Gondor heralds “an effective Holy Roman Empire with its seat in Rome [rather] than anything that would be devised by a `Nordic.’”

If an eyebrow is raised at the thought of Tolkien and the classics, the eyes positively pop at the thought of Tolkien as a utopian. An infantry officer at the Somme, here is what he wrote at the conclusion of WWII after serving in the Home Guard:

There is a stand-down parade of Civil Defence in the Parks in the afternoon, to which I shall prob. have to drag myself. But I am afraid it all seems rather a mockery to me, for the War is not over (and the one that is, or the part of it, has largely been lost). But it is of course wrong to fall into such a mood, for Wars are always lost, and The War always goes on; and it is no good growing faint!

This is not just Tolkien in a mood. It was a deeply held position. The urtext of the legendarium, The Silmarillion, begins with war breaking out even before God has completed creation.

Lecturer in Classics at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands, Williams means something rather specific by utopianism. As with the ancients, utopianism in Tolkien is a method of critique, an exploration of ideas about value order. The idylls of the Shire, Rivendell, and Lothlórien stand in judgment of the dystopian Moria, Isengard, and Mordor. For Williams, Tolkien’s thinking evokes a classical frame, philosophically “establishing precisely which ideals or values were evident in better, relatively more perfect, past communities.”

The premise of the book is an intuition ably validated by Williams, though perhaps with overreach. The premise is that Tolkien’s pre-WWI elite education meant his mind was saturated with the classics. Classical literature must then have shaped his writing in some noticeable ways. Tolkien tells us that he never warmed to the classics and did not like Greek civilization. In the just-released, expanded edition of Tolkien’s Letters, which Williams had no access to, Tolkien explains to his son, Christopher:

It is part of the nasty Hellenism in which we (certainly I) was brought up, in which that highly dubious character Socrates became more than a saint. The Ancient Greeks were for all their talents, a very nasty people of degraded habits and revolting attitude to women, and profoundly disliked by those among them whom we are supposed to take as representative—such as Plato.

Tolkien disapproved then, but also leaves us in no doubt that he was steeped in the classics and never got too far from them since an English professor’s duties at Oxford once included marking the Latin exams of undergraduates. Williams identifies three themes from classical literature that shape Tolkien’s writing—narratives of hospitality, the sublime, and decline and fall.

Hospitality

To explore the common theme of travel far from home in Tolkien, Williams turns to Homer’s Odyssey and its portrait of hospitality. Of course, Williams stresses that the ethics of hospitality is one of the great topics of myth in all civilizations, but Williams identifies striking similarities with Homer’s specific treatment that helps us think afresh about The Hobbit. Tolkien’s first book and perhaps the most cherished is markedly different from, as Williams puts it, the “grand geopolitical scale” of The Lord of the Rings.

Hospitality has a prominent place in the tale. The story begins in Bilbo’s home with the reluctant but generous hospitality he gives to Gandalf and the dwarves. It includes the much-loved scene by the fireside of the trolls and the negotiated welcome Gandalf’s party receives in the home of the shapeshifting Beorn. The book closes with the dwarves reclaiming their ancient home from the dragon Smaug. Tolkien grew the story from the bedtime tales he would tell his children and Williams contends that The Hobbit is an “ethical scrutiny” into what makes a good and bad home.

Throughout his life, Tolkien had a recurring nightmare of an enormous wave washing all away. In his letters, he frequently mentions Atlantis. In the legendarium, Númenor is washed away by a retributive tsunami of the gods.

“Odyssean reception can also be found in the religious background to various hospitality scenes in the children’s story, which posits benevolent hospitality as essentially absolute, as watched over by a magical, supernatural, even divine order.” Calypso’s cave has a “great fire” that is a welcome to Odysseus on his travels. Later, the cave becomes his prison, his detention blocking his desire to get home. Calypso is forced to release the traveler by the intervention of higher divinities. Throughout The Hobbit, Gandalf stands as a corrective for each infraction of the hospitality principle.

Strong pages include a close reading of Tolkien’s humorous troll passage. Williams acknowledges the Nordic heritage of trolls but points to Homer’s ogre host Polyphemus as a template. The ogre eats his guests, but they had also planned to raid him. The cyclops is a primitive chef just like William and his pals, and the dwarves get caught and readied for eating because Bilbo tried to pinch food from them. In the Odyssey, the feast of the giants is interrupted by a linguistic trick and Gandalf saves his traveling band similarly.

After this encounter, the hobbits are guided by Gandalf to Elrond’s house. There are similarities with the island-palace of Aeolus. Odysseus arrives there after his encounter with the giant man-eaters. Both homes are out-of-the-way places, little utopias watched over by authorities with divine-like magical powers. Aeolus is master of the winds and Elrond has power over the rivers. Each offers grand hospitality, Elrond’s home, relays Bilbo, “was perfect, whether you like food, or sleep, or work, or storytelling, or singing, or just sitting and thinking best.” In both stories, stays in such paradises are short, pointing to a glimpse of a joy not typical of human life. Williams points out that the orphaned Tolkien lived in no less than nine different homes between 1892 and 1904.

Sublime

Ovid’s orphic Old Forest is a template for the many examples in Tolkien of transcending the ordinary through experience of nature, contends Williams. In addition to the voluminous commentary on Tolkien as an eco-writer, Williams argues that Tolkien’s dense detailing of the natural world relies on the Roman literary device of nature as an encounter with the sublime. As many have pointed out, Tolkien is not straightforwardly a champion of nature. The hedge about Buckland does constant battle with the trees of the Old Forest that would take over the pastures of the Shire. Tolkien’s oft-stated attachment to trees does not exclude his Old Forest from being a bewildering place that has something in common with ancient Orphism played out in “the archetypal forest” of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Ovid’s forest is dark, destructive, and numinous and Tolkien’s Old Man Willow is similarly a “quasi-divine figure of destruction.” A malign presence in the forest, the willow’s influence is offset by Tom Bombadil. Bombadil is “in line with the Ovidian motif of finding a god in the central glade of the sacred grove.” Encountering Bombadil in the woods, the disoriented hobbits are inducted into rare knowledge as Bombadil “told them tales of bees and flowers, the ways of tress, and the strange creatures of the Forest.” Williams points out that Orpheus’s recital of a long list of trees could hardly have failed to make an impression on the tree-loving Tolkien. As Williams astutely points out, Tom also has a bit of the Bacchus about him. Tom would never indulge the manic Dionysian rites, but he has a mad-cap quality and a definite “best not disturb” mood attached to him since it is indicated that he has tremendous reserves of power despite his jocular silliness. Even the august Lord Elrond, who is over six thousand years old, admits that he is completely mystified by the orphic Bombadil.

Narratives of Decline and Fall

Middle-earth is dotted with the ruins of earlier ages. For example, the dwarf mines of Moria and Gondor’s Argonath both speak to greatness long lost. In classical literature, lapsarian narratives, Williams tells us, are “a means of reflection on utopian communities,” a device used “to reinforce definite moral and social virtues.” Throughout his life, Tolkien had a recurring nightmare of an enormous wave washing all away. In his letters, he frequently mentions Atlantis. In the legendarium, Númenor is washed away by a retributive tsunami of the gods.

The moral meaning of Númenor is tricky. In Williams’s gloss, Númenor transitions from a moderate occidental island realm to an expansionist orientalized kingdom. This expansion brings ruin. Númenor in its infancy points to a core value in Tolkien of “ontological moderation.” I think this point is very strong. For Tolkien, respectful of the limits placed upon us by the gods, rule should always be temperate and restrained. This important observation leads Williams to a perceptive portrait of Faramir. He is the only character in The Lord of the Rings who prays. His hideout in Ithilien is “plain and unadorned for the most part.” He consciously looks west to old Númenor, to “that which is beyond Elvenhome and will ever be.” However, it is too strong to link Númenor to our Occident. Williams writes, “It is a means of establishing what ideals or virtues defined the once-utopian community of Númenor—a moderate, pious, ascetic, economically insular, sophocratic and, to an extent, ideally Occidental community.” Here, Williams drifts too close to Greek history, I think. He parallels Númenor to the experience of Athens once too involved with Persia: in the classic telling, a case of the corruption of empire bleeding through and corroding Athenian republican virtue.

To understand Tolkien’s Númenor right, myth, not history, is needed. The struggle between sea and land is a staple of myth. Geopolitical thinkers have used the myth of the conflict between the Leviathan and Behemoth as a template for thinking about the basic tension between sea and land powers. Númenor’s fall reflects this tension. In Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth, Tolkien compresses this tension into the fraught relationship between King Melendur and his son, Aldarion, a sea captain. “Melendur looked coldly on the enterprises of his son, and cared not to hear the tale of his journeys, believing that he sowed the seed of restlessness and desire of other lands to hold.” Melendur warns his son to no avail that his love of the sea will make him forget what is owed the gods and their Ban on sea-borne adventuring. Aldarion develops Númenor as a sea power, a path that ultimately provokes divine cataclysmic punishment. Tolkien’s story, I believe, traces not to Greek history but a mythic worry about the sea as an immodest subverter of boundaries.

Before concluding, I should note that I wish this good book had been edited differently. Another version of this book would have been welcome amongst the classical education movement in the US. There is a significant interest in Tolkien amongst these students, as seen for instance in the Agathon Institute in Syracuse. However, the volume is written in a language typical of modern university scholarship with good ideas clouded by phrases like “gothic genre-codes” and “retrotopianism.” It would read so much leaner if ordinary language had been used throughout to develop concepts. Regular conservative readers would have enjoyed Williams’s treatment of Tolkien’s conservatism, the worth of which can be glimpsed in “an imperial `Augustan’ regency backed up by a Platonic sophocratic nobility, with perhaps further medieval class hierarchies implied.” For those interested in Tolkien, I strongly recommend this book and just advise barreling through some of its phrasing.