In a courageous 1933 lecture, Wilhelm Röpke explained the value of liberalism—a message still worth considering today.

Why Orwell Lives On

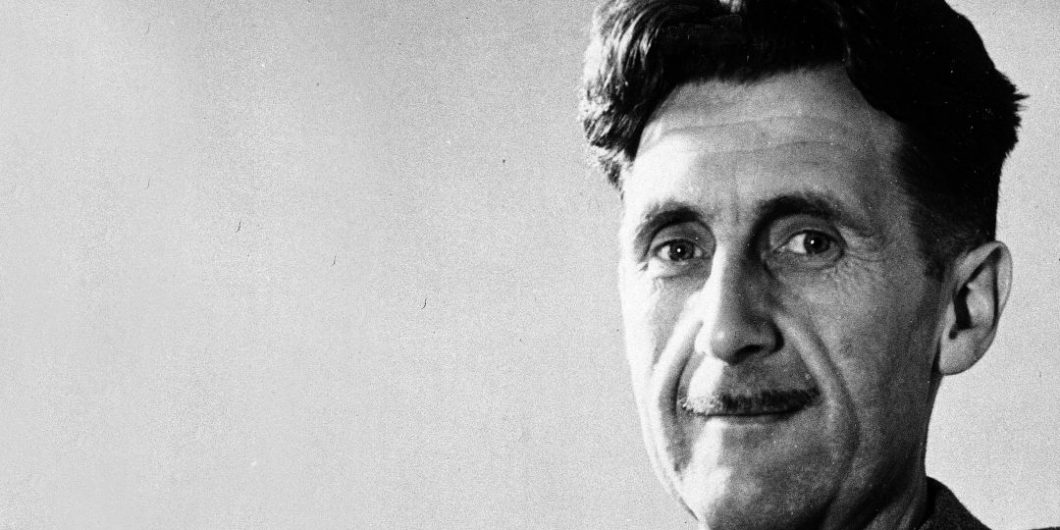

Eric Blair, better known to us as George Orwell, is one of those writers who is experiencing a renaissance in light of the controversies of the twenty-first century. Our own political and journalistic language take from him and invoke him: “thought-police,” “newspeak,” “Orwellian,” “1984.” Why, though, does Orwell live on and why do we still find him so important, so enduring?

D. J. Taylor gives a new account of Orwell’s life in Orwell: The New Life, one that is informed by the “vast amount of new material that has come to light” since the author’s previous biography in 2003 about one of modern Britain’s greatest writers. There is, as Taylor notes, something deeply “personal” about our attraction to Orwell. He is not a distant writer, an abstract thinker, a hidden intellectual. We feel that he is one of us, someone with whom we can instantly identify and recognize. I knew this was true of myself when I first read Orwell in high school; he happened to be one of the few “great” authors we read in class that I instantly enjoyed.

Taylor’s “new life” of Orwell is a brilliant and masterful presentation of Orwell from early childhood to his untimely death. We first learn of Orwell’s family lineage, how it dotted across the globe, itself a foreshadowing of Orwell’s own adventures across the British Empire. We then meet him at St Cyprian’s, a school of the new middle class, where he excelled on scholarship, “Within three weeks of arriving at St Cyprian’s he was top in history and joint top in French. A month later he was second in Latin and top in arithmetic.” Early on it seemed like he was destined for greatness.

After St. Cyprian’s, he attended Eton, the school where most of Britain’s next elite were educated (and still are) before attending university (usually Cambridge or Oxford). He arrived as a King’s Scholar, his expenses (minus living) paid because of his merit from St Cyprian’s. While at Eton, though, he squandered away his intellectual brilliance by doing bare minimum work. Graduation didn’t leave a young man like him—from the new middle class instead of the landed aristocracy, who had dwindled away his prospects for Oxford and Cambridge—with many options. So he set out for Burma to work as a policeman. Eric Blair would become George Orwell as a result, seeing firsthand the machinations of oppression and resentment, hope and liberation, freedom and tyranny.

It was in Burma where he witnessed power dynamics at work that left a major impression on him. Seeing colonial rule up close, how it was administered, the resentment and violence between various tribes and people, and how it was used to divide and rule, left a bad stain in Orwell’s eyes and mouth. Upon returning to England due to illness and becoming a freelance journalist, Blair changed his name to George Orwell to cope with the brutality he saw. His friends said Orwell named himself after the king and the beautiful River Orwell with its picturesque serenity. Orwell wanted a new beginning, but he never forgot what he witnessed in Burma.

The early life of Orwell recounted by Taylor is very illuminating as it brings personality and spunk to the writer we know from his novels, perhaps some of his essays, and his other writings like Burmese Days and Homage to Catalonia. The teenage Orwell, with his failed romance with Jacintha Buddicom, and his struggles witnessing imperial abuse in Burma, formed some of the pillars with which his more famous novels would deal: imperfect families, the problem of love, the jackboot of oppression, and dehumanization. It is also a deeply personal Orwell we encounter in Taylor’s pages, a man with a name, a heart, and a face like the rest of us, trying to juggle the complexities of the human condition and experience in a world that was ruined by the horror of World War I and soon to be ruined by the catastrophe of World War II. We may know Orwell’s photos, but Taylor helps bring vitality to the man many of us only know through black and white headshots on the internet. (On this note, the pictures included in this biography are wonderful as we see the young Orwell and family and friends, too.)

What makes Orwell such a compelling and fascinating writer isn’t that he lived through the seminal events of the first half of the twentieth century, which is true for many, but that he often participated in them. It is one thing for a writer, or a journalist, to sit back in their cushy office and write about what they read is going on in the world. It is another thing for a writer, or a journalist, to be present on location. Orwell saw firsthand life in the overseas territories of the British Empire. Orwell sat in the trenches of Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Orwell lived through the bombings of the Blitz. All of this made Orwell the man we know through his writings, especially his novels.

To this end, Orwell’s place in the crisis of modernity becomes apparent. Taylor notes the oddities that make him, in our now polarized age, such a common-ground figure, even if he was, and always remained, a “man of the left” and a “socialist” throughout his life. “At the heart of Orwell’s worldview, it might be said, lies modern man’s struggle to come to terms with the absence of God and the need for a secular morality that would somehow replace a value system built on the belief in an afterlife. Orwell’s own views on religion are relatively complex. … His final position was that of a man who rejects the existence of God while regretting the decay of Christianity’s cultural influence.” This, however, helps make sense of the impossibility of love in Orwell—both in his writings, like how Winston and Julia cannot truly love each other and are ultimately torn away from one another, and in his own life as he was an adulterer and terrible husband to his first wife, Eileen.

If Orwell sought to salvage “Christianity’s cultural influence” without its metaphysics, it is unsurprising that Orwell ultimately struggled with Christianity’s greatest cultural gift: Love. What really separated Christianity from the Greek philosophies and pagan religions that preceded it was how God is conceptualized as Love itself. “God is Love” (1 John 4:8) reorients the Christian understanding of Scripture, the nature of Deity, and the very nature of ourselves as images of love. The loving-kindness and compassion preached by Christianity make sense, as the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche understood, only from its acceptance of God as the alpha and omega. Orwell sought a secular agape willed by humans, but humans are now the alpha and omega rather than soulful expressions of Beauty and Love. But this outlook, Nietzsche also understood, means love cannot truly exist; all that exists is the will to power. Orwell missed the one thing Nietzsche was most prescient about.

Orwell still matters because many—especially among the intellectual class—are clinging to Orwell’s desire for a Christian moral life without the Christian God.

Thus, Orwell is left in a conundrum. He desires to “devise a secular morality that encourages men and women to behave decently and cling to the moral teachings of Christianity without threatening them with eternal hellfire or promising them a seat at the table of Paradise.” But the other side of Christianity that Orwell doesn’t want to hold onto is the corollary of a metaphysic built on love, the understanding that God is Love and Love is the source and purpose of existence. The “moral teachings of Christianity” stand with the existence of God because Christian morality, rooted in Love, finds its coherence only if Love itself exists and is the beginning and end of all things.

To an exhausted modern world that agrees with Nietzsche and Orwell, which has disavowed belief in God but still desires an ethical core of compassion and kindness, it is no surprise that Orwell drifted into a benign socialism and remained there while criticizing the excessive violence and abuses of socialism where he saw it and why so many today follow a similar path. This earned him, as Taylor explains, his few and only true enemies. “Apart from a handful of score-settling Stalinists who remembered [Orwell] from Republican Spain, thought Homage to Catalonia a travesty of what had really happened in Barcelona and feared its author’s strictures on the fellow-travellers of the post-war left, there were very few people that hated Orwell.”

This explains how Orwell, who so vigorously opposed fascism in Spain and then Nazi Germany during World War II, has ended up as a highly praised intellectual of anti-communism from the right with only faint declarations from leftwing writers that Orwell was a socialist but nothing more substantive than that bland corrective. Orwell knew that fascism, horrible as it was, was a passing fad. Despite media pretensions to the contrary in 2023, it still is. The real “enemy” was the brutal and inhumane socialism of Stalinism which Orwell saw with his own eyes in the trenches of Catalonia and the hypocrisy of the stories coming out of the Soviet Union. No surprise, then, that his most famous novels—Animal Farm and 1984—read more as a critique of the hellfire and lies of a variant of socialism than the shortcomings of capitalism or the faded danger of fascism having just been defeated by the Allies.

Yet the real allure of Orwell runs deeper than political commentary and prophetic insight into the struggle with totalitarianism. “Orwell’s writing returns to the human face with the regularity of a homing pigeon,” Taylor writes. “As well as having a merciless eye for facial peculiarities, he was fascinated by their habit of conveying characteristics—the personality, the temperament, in extreme cases the ideology—of what lay beneath the skin.” Even in animal form, Orwell’s characters are alive with personality, with uniqueness, with distinctiveness. It is as if we know them and love them.

In an age of dehumanization, which the twentieth century certainly was in most places, Orwell’s writings are not merely trying to wrestle with the opiate of the intellectuals—the death of God—they are also humanizing in ways other great English writers of the same period are not. Orwell was right to reject Graham Greene who eventually glamorized sin and evil in Brighton Rock and The End of the Affair. Orwell’s characters, by contrast, are truly tragic and captivate us because they want to be good in a world stripped of goodness, where goodness and beauty have withered away, and all that is left is the “startlingly bleak” anti-humanism of totalitarianism.

Many of us who are living in the aftermath of two world wars and now the horror of another brutal war in Ukraine are left wondering: Where is the beauty and goodness that other writers have suggested to save the world? Orwell’s writings grip us because we glimpse the goodness and beauty of the personalities and faces of his characters, the brief hopes and smiles of their tiny victories in a dark and ugly world, the very goodness and beauty we ourselves seek. However, Orwell’s endurance is also his shortcoming: without God, there can be no benign morality, no secular agape to dedicate our lives.

Orwell still matters because many—especially among the intellectual class—are clinging to Orwell’s desire for a Christian moral life without the Christian God. Thus a mystical socialism endures as its substitute despite all the atrocities its disciples have committed, atrocities that Orwell criticized and publicized to the world. But Orwell’s characters do not achieve that secular agape that the author so desired. Their faces are ripped away from us. Boxer disappeared, never to be seen again. Winston and Julia are torn apart. The inhumane face of Big Brother is what Winston sees at the end of Orwell’s most Orwellian writing. This is ultimately telling to the attentive reader. As Saint Augustine said, “There is no love without hope, no hope without love, and neither love nor hope without faith.”

Orwell: The New Life by D. J. Taylor is undeniably the best biography of George Orwell now written. We meet the boy, then the man, who has held captive our imagination since his death because we share the same fears and worries as he did. We see him at school, working as a policeman in Burma, in the trenches of Spain, then sifting through the rubble of war-torn England. We who have the courage to stand up to the inhumane brutalism that still assaults our world and our faces gain much in having a friend in Orwell. However, Orwell ultimately points us to a deeper reality that he himself seemed unable to accept despite his genius.