Danegeld Justice

Perfect justice is no doubt unattainable in this sublunary world, but whenever I gave evidence in court in a case involving tort law, I had the strong suspicion that I was participating in something deeply corrupt (and corrupting). Justice, as it was administered, was a game of poker rather than a matter of truth as to who had done what to whom. Sometimes the very law had corruption written into it. For example, a party only partly responsible for a harm was deemed wholly responsible for any compensation due.

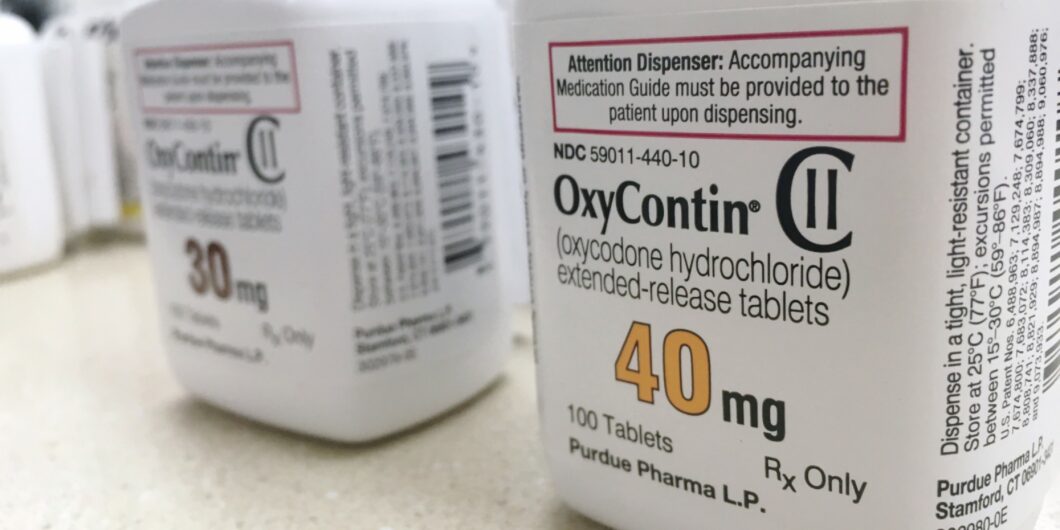

I read with unease that Publicis, the large French advertising agency, had agreed to pay $350 million to states for its part in the promotion of oxycontin, the opioid whose prescription was the detonator of the huge wave of deaths by opioid overdose that has since engulfed America, causing (according to a paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association), 422,605 deaths between 2011 and 2021, and now causing one in twenty-two of all deaths in America. The epidemic has escaped, so to speak, its historical origins, but that does not absolve those responsible for its origins. Although counterfactuals are always impossible to prove, it seems likely that without oxycontin and other such drugs, the epidemic would not have occurred.

Publicis has neither admitted nor been convicted of any wrongdoing. I hold no brief for advertising companies, and whether Publicis did anything wrong knowingly, either from a legal or moral point of view, I cannot say, though I have my private suspicions. But from the point of view of justice, the extraction of the money from the company seems more like an arbitrary tax or imposition than real compensation for harm done.

In the first place, the money will not go to any individuals most affected by the deaths. At best, it will go to a bureaucratised structure whose aim, supposedly, is to reduce if not eliminate the problem. The auguries are not good: the National Institute on Drug Abuse consumed about $10 billion in the very years cited above, without making any noticeable difference to the epidemic. In essence, much of the money will go to subsidising employment.

In the second place, if responsibility other than that of the people taking the drugs must be fixed, there are much better candidates than an advertising company: the FDA and the CDC, for example. Because I had a certain interest in the subject, I noticed the rapid growth in the number of deaths from opioid overdoses back in the early 2000s. If a rather lowly and unimportant observer such as I noticed it, why did those two agencies, with all their resources and their powers, react so little and so late, and then do so little?

Doctors should not have been susceptible to propaganda in favour of drugs that they could and should have known carried great risks.

The medical profession, or many members of it, were also culpably responsible. There was a concerted effort by some doctors to establish pain as the so-called fifth vital sign, in addition to the four traditional ones of heart and breathing rates, temperature, and blood pressure. This is because of a widespread view that pain was being inadequately treated (it is still very difficult to treat). But the promotion of the view that it was the fifth vital sign opened the floodgates of careless or stupid opioid prescriptions.

The most elementary consideration should have alerted doctors to the falsity of the view that pain should be considered the fifth vital sign, and they should thereby have been cautioned against prescribing opioids to whoever complained of pain of whatever kind. The fact is that pain is not a sign, but a symptom; it is not what is observed in, but what is felt by, the patient.

True enough, the experience of pain can give rise to observable behaviour, and this is often correlated with observable pathology. But it requires very little medical experience to know that not all pain is the same, that people react to pain very differently, that acute and chronic pain are very different, physically and psychologically, and so forth. How much medical experience was necessary for doctors to know that opiates and opioids are often taken for reasons other than the relief of pain?

That pain could not be a sign, let alone a sign requiring immediate or quick resort to opioids, should have been enough to alert doctors to the dangers of careless prescribing. The fact that it wasn’t, at least for large numbers of doctors, suggests that they had been trained without being educated, though perhaps there were other reasons too: some of them were corrupt and in effect sold prescriptions, while others were afraid to refuse patients what they wanted. The least that might be said is that doctors should not have been susceptible to propaganda in favour of drugs that they could and should have known carried great risks. And this was not a problem confined wholly to practices with patients who were especially susceptible to drug abuse. I have known patients who had absurdly large quantities of such medication pressed on them when they went home post-operatively that they did not need.

Ascribing proportions of responsibility for the origins of the disaster is obviously difficult and cannot be exact. But the money paid by the advertising agency resembles as much the result of a shakedown as a just punishment after due process for proven wrongdoing (though I can conceive that a just punishment, once everything is known, might be even more severe). Still, to extract money by threatening the possibility of something even worse, and then spending it on an activity of doubtful value, or an activity that could be easily funded some other way, seems to me scarcely dignified, or even compatible with the rule of law. One might designate our society increasingly as a Danegeld society, in which, without having done anything wrong, we feel obliged sometimes to head off worse depredations by means of unjustified payment. The Dane and the payer of the Danegeld are in a dialectical relationship, for:

We invaded you last night—we are quite prepared to fight,

Unless you pay us cash to go away.

But:

… if once you have paid him the Dane-geld:

You never get rid of the Dane.