The father of David Maraniss got blacklisted for being a communist, but never publicly explained why he’d been one or why he gave up on communism.

His Russia Collusion Was More than Evident

Harvey Klehr’s new book, The Millionaire Was a Soviet Mole: The Twisted Life of David Karr is a rarity: a biography of a man so interesting that you wonder why you never heard of him before. Of course, a biography of someone unfamiliar to the vast majority of readers is a bit of a difficult sell for those uninitiated into the work of Klehr, the Andrew W. Mellon Professor Emeritus at Emory University. In a perfect world, Klehr’s groundbreaking contributions as a historian would automatically make any new book of his a matter of significant public interest.

But as it happens, the 73-year-old’s life’s work amounts to reporting on the history of the communist movement in the United States, and a significant part of that amounts to his uncovering the startling extent to which various influential Americans and U.S. institutions were willing participants in Soviet espionage. It’s clear that our political Left, our academics, and our journalistic establishment (but I repeat myself) would gladly ignore Klehr’s scholarship altogether.

In 2009, when he played an instrumental role in showing that the beloved left-wing journalist I.F. Stone had worked as a Soviet spy, the response from the mainstream press included a great deal of denial and even outrage directed, not at Stone for selling out his country, but at Klehr and fellow historian John Earl Haynes for their temerity in having unearthed this inconvenient fact. A decade after this revelation, the Nieman Foundation at Harvard is still handing out the “I.F. Stone Medal for Journalistic Independence” even though “journalistic independence” is an unworthy appellation to use for a man who, it turns out, was paid to propagandize on behalf of a foreign government responsible for as many as 100 million deaths in the 20th century.

While The Millionaire Was a Soviet Mole contains no truly groundbreaking information on a par with much of Klehr’s heavyweight scholarship, it makes up for this by being an engaging book about a fascinating man. Indirectly, Millionaire is also a wonderful introduction to the general topic of American communism—just think of the book’s subject as a malevolent Forrest Gump. “It often feels like David Karr has been an inescapable presence in my life,” Klehr writes in the acknowledgments. “He has been around for nearly thirty years, sometimes part of my work virtually every day; sometimes hovering in the background.”

So then, who exactly was Karr, and why should we care enough to read 255 pages about him?

A Red Enters the Writing Racket

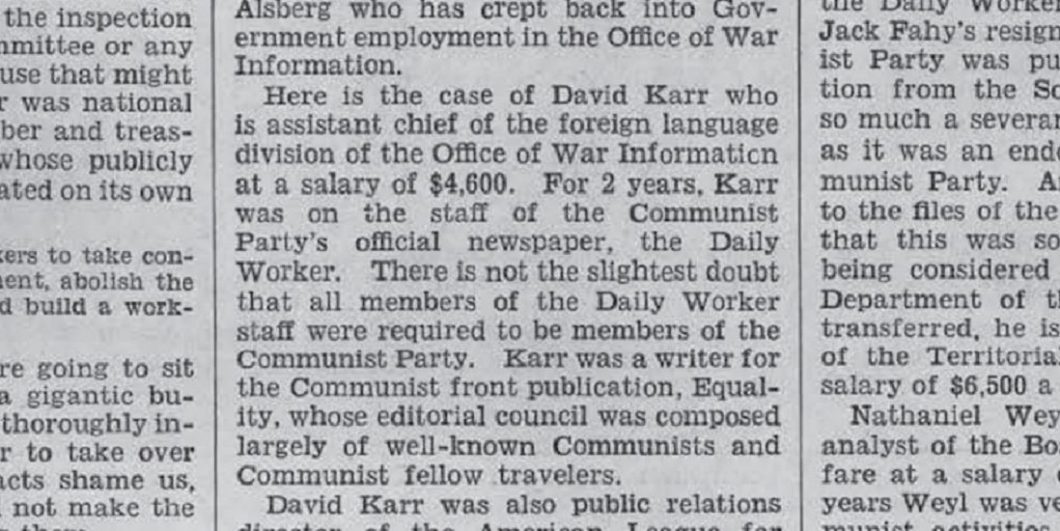

Born David Katz in 1918 to a prosperous Jewish family in Brooklyn, he wasn’t much of a student but got involved in organizing newspaper unions while still in high school and pursuing his dream of being a sports reporter. Having changed his surname to Karr, presumably to avoid anti-Semitism, the high school graduate and budding journalist soon found himself writing for a string of radical newspapers, including the Daily Worker, the official organ of the Communist Party of the United States of America.

The young Karr was constantly on the make, and parlayed this experience into mainstream journalistic work that brought him to the nation’s capital in 1941. With the United States entering the war, he then fell into a government job at the Office of War Information, despite having lied about his credentials, and also despite some FBI concerns about his radical ties. A big part of his OWI job was barnstorming across the country to drum up support for the war effort from the ethnic organizations and newspapers that abounded in the hinterlands. By all accounts Karr, an indefatigable self-promoter, was good at the work.

This is the heyday, or toward the end of the heyday, of American communism, and some of the ethnic enclaves Karr visited placed him in contact with not a few CPUSA members and fellow travelers. By 1943, he would find himself in the crosshairs of a congressional investigation—and not for the last time. Three years previously, he had accused Congressman Martin Dies (D-Tex.) of consorting with fascists. Dies was chairman of the House Special Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities, and when he found out Karr was now working within the U.S. government, the congressman began to make a stink about the OWI employee’s ties to the Daily Worker and other communist organizations. Karr claimed, unpersuasively, that he had acted as an FBI informant while working for the radical Left. Even as the FBI was trying to sort this out, he resigned from his OWI position when a Civil Service Commission report delivered a recommendation that he be fired.

One might think that being at the center of this kind of public controversy would mean the death of one’s career. But the biographer quotes a colleague of Karr’s, to the effect that he was known for “getting around as quick as an octopus on roller skates.” Within months, he had made himself a busy aide to Franklin Roosevelt’s left-wing vice president, Henry Wallace, and was being paid (off the government’s books) to go around the country once again—this time to try to whip up support for keeping Wallace on the presidential ticket in 1944. Karr appeared with the Vice President at a number of notable public events. (Wallace, who did get bumped from the ticket, was not a communist but his avidly pro-Soviet stance endeared him to the CPUSA and others on the leftmost edges of American politics.)

After the Wallace interlude, Karr went back to journalism, where he promptly got fired from a job on the city desk of the Washington Post, and almost as promptly got hired as a “leg man” for Drew Pearson’s legendary “Washington Merry-Go-Round” syndicated column. (That column was still being written until Karr’s former colleague Jack Anderson died in 2005; Brit Hume of Fox News worked for Anderson’s iteration of the column as a young journalist in the 1970s.)

Though a mandarin of American journalism, Pearson was by many accounts one of the most scurrilous reporters to ever draw breath. Under his tenure, “Washington Merry-Go-Round” was simultaneously one of the most popular columns in the country and also a clearinghouse for gossip, personal political agendas, and vicious score-settling. Pearson was sued for libel 275 times over his career, even going so far as to blackmail Douglas MacArthur to get the general to drop his lawsuit against him. Klehr quotes a senator saying it was impossible to call Pearson an “SOB” because he was “his own filthy brainchild, conceived in ruthlessness and dedicated to the proposition Judas Iscariot was a piker.”

All of that is to say that Drew Pearson and David Karr were a match made in heaven. Klehr, already having ably documented that his subject was a chronic liar willing to say absolutely anything to get ahead—up to and including trashing his own wife’s reputation to the FBI—recounts several egregiously unethical things that Karr did to get scoops for Pearson. His boss and he got along well in no small part because Pearson shared Karr’s left-wing sympathies. There were numerous rumors that Karr was the conduit through which the notorious State Department official and Soviet spy Alger Hiss leaked to Pearson; but Klehr notes that this cannot be proven.

Can’t Keep a Bad Man Down

With the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Cold War, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisc.) was making himself into a folk hero for purporting to root out Reds in the government. Pearson, having made plenty of enemies in Washington, was no communist but he was vulnerable. A rival columnist started stirring up public outrage and scaring advertisers away from “Washington Merry-Go-round” by highlighting Karr’s communist past. Pearson officially let Karr go, but the two men continued to work together on the q.t.

Because you apparently can’t keep a bad man down, Karr moved back to New York to work in advertising and public relations, gaining clients who were some of America’s biggest industrial tycoons. Karr worked for Henry Kaiser of Kaiser Permanente and liquor magnate Louis Rosenstiel, the latter of whom being Karr’s main source of income at the time. (Rosenstiel’s ex-wife would later famously claim that he took her to a party where McCarthy aide Roy Cohn introduced her to J. Edgar Hoover, and the FBI chief was “wearing a fluffy black dress . . . lace stockings, and high heels.” Notwithstanding the anecdote’s place in the pop history firmament, Klehr rightly notes that there are many convincing reasons to doubt the veracity of her account.)

While doing PR for the corporate raider Robert Young, Karr thought to go into business himself. Through a series of machinations too detailed to recount, he was soon embroiled in a successful corporate takeover operation. In just a few years, Karr went from a disgraced journalist-turned-flack to being the CEO of Fairbanks Whitney, a company that employed 5,000 people and had annual sales of $150 million. Around the same time he was scaling the corporate heights, two of his friends, theatrical producers Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin, were adapting a book for the stage, and they told Karr’s wife that the play’s main character—a window cleaner who becomes a CEO “by using every dirty trick in the book”—reminded them of Karr. Angered by the comparison, David Karr would later refuse to attend a party celebrating his friends’ play, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, before its premiere in 1961.

Predictably, Karr’s tenure at Fairbanks Whitney, while personally profitable, was not a business success. He got ousted as CEO after only a few years. (Among other problems, the firm had government contracts and, once again, Karr’s communist past became an issue.) Time for another career shift. Karr moved to Los Angeles and, using a range of contacts he’d developed going back to the Drew Pearson days, soon set himself up as a movie producer. He would eventually coproduce the Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth movie The Money Trap (1965), the television movie The Dangerous Days of Kiowa Jones (1966), and Welcome to Hard Times (1967) starring Henry Fonda.

Then came Karr’s remarriage to a woman from a wealthy French family and his relocation to Paris, where he hobnobbed with the Rothschilds and other European elite. In 1968, he appears to have flown back to the United States so that he and Pearson could personally inform President Johnson that former First Lady Jackie Kennedy was going to enter her second marriage, to the shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. Karr, in this period, had become an associate of the Democratic politician and Kennedy brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, and also of the notorious pro-Soviet businessman Armand Hammer. It was these connections that enabled Karr to start wheeling and dealing in the Soviet Union, as well as enter Democratic Party politics at the highest levels. Our Brooklyn-born Gump was now rubbing elbows with the likes of California’s new young Governor Jerry Brown and President Carter himself.

Klehr painstakingly demonstrates that Karr was reporting on his acquaintances’ political activities to the KGB. There are also some notable asides about the extent of Senator Ted Kennedy’s eyebrow-raising back-channel communications with the Soviets. Karr died in a Paris hotel almost exactly 40 years ago in July, 1979. His unexpected death at age 60 came under mysterious circumstances. His wife halted the burial so an autopsy could be performed (no foul play was determined) even as rumors swirled that he had swindled Russian business partners and may have been the victim of a “wet job” by either the CIA or the KGB.

Plus Ça Change . . .

If you think all the details recounted above give you a good picture of Karr’s life, guess again—neither his four stormy marriages nor the various theories about the role he may have played in the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy have been touched on. It’s remarkable how much living the man packed into his 60 years, and it’s also a real tribute to Klehr that The Millionaire Was a Soviet Mole is tightly organized and dispenses a torrent of information without managing to leave the reader confused. (I will confess that the book did send me scrambling to Google a few times for more context on the 20th century notables and references it mentions.)

In the end, it’s one helluva life story, and Klehr judiciously stays out of the way and lets the facts render judgment on Karr. Nonetheless they are facts that, once again, ought to cause mainstream historians to reassess how they have consistently downplayed the Soviets’ reach into key U.S. institutions. And aside from providing a lot of insight into American communism, Karr’s close associations with several high-flying mid-20th century figures are a good reminder that there’s nothing new under the sun. If the Trump era has ignited sudden and pressing concerns about foreign meddling in our politics, fake news, FBI surveillance, and the level of trust we can put in our leaders and our institutions—well, many of the shenanigans described in this book make a persuasive and highly entertaining case that things have been worse.