A life of the late David Karr—Daily Worker writer, film producer, confidante of columnists, acquaintance of U.S. Presidents . . . and asset of the KGB.

The Cost of Fealty to Tyranny

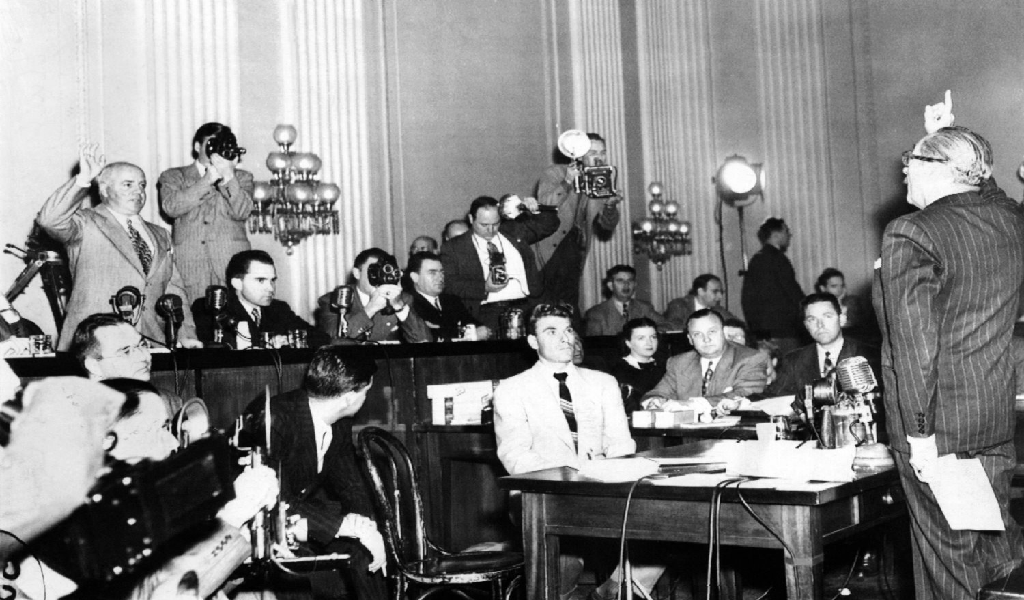

David Maraniss, associate editor of the Washington Post, has won two Pulitzer Prizes for journalism and written best-selling biographies of Barack Obama and Bill Clinton among a dozen books. A Good American Family: The Red Scare and My Father is his account of Elliott Maraniss, also a journalist, who was named as a member of the Communist Party of the United States of America at a hearing of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, lost his job, and was blacklisted for five years.

Maraniss tells his father’s story interspersed with portraits of several other people who played major roles in that family drama: HUAC’s chairman at the time, Representative John Wood (D-Ga.); Bereniece Baldwin, a long-time FBI informant in the CPUSA, who named Elliott as a communist; Frank Tavenner, HUAC’s counsel, who questioned him; his lawyer, the future U.S. Representative George Crockett (D-Mich.); Arthur Miller, the famous playwright who had preceded Elliott Maraniss as a staffer on the student newspaper at the University of Michigan; U.S. Representative (later U.S. Senator) Charles Potter of Michigan, a HUAC member who had lost both his legs during World War II; Bob Cummins, Elliott’s brother-in-law, a communist who had fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain and refused to answer HUAC’s questions; and Coleman Young, another defiant witness, later elected the first black mayor of Detroit.

It’s a compelling and fascinating account. Yet there is some missing information, particularly about exactly what the author’s father did in the CPUSA, exactly when he joined, when (and why) he left. It appears his mother was already in the Young Communist League when she met her future husband and was more dogmatic than he was. Maraniss admits that his parents were loath to discuss their Party experiences. He tells us he could not write this book until both had died. One of the few comments the father made to the son on this subject was to characterize himself politically as “stubborn in my ignorance and aggressive in my prejudice.”

To Maraniss’s credit, he does not excuse the political choices his parents made. Nor does he hide his dismay at their loyalty to the Soviet Union and the unconscionable policies they supported while Party members. They had, he writes, “latched on to a false promise and for too long blinded themselves to the repressive totalitarian reality of communism in the Soviet Union.” And they paid a price.

Fired

Elliott, a Jewish kid from an immigrant family in Brooklyn, went to the University of Michigan determined to be a journalist. Pulled to the Left by the Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe, he became, if not a card-carrying member of the CPUSA, then a full-throated ally during college. Covering a campus celebration honoring two former students who had just returned from Spain—a third had been captured and executed by Francisco Franco’s forces during that 1936-1939 conflict—he met Mary Cummins, sister of one of the returnees, and they soon married. Despite their professed antifascism, Elliott and Mary supported the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939. Elliott’s editorials in the student newspaper suddenly endorsing the isolationism he had previously scorned drew intense criticism.

At the time of Pearl Harbor, Elliott, by then working at a Detroit newspaper, enlisted in the U.S. Army. A negative military intelligence report nearly derailed his effort to obtain an officer’s commission, but he was eventually put in charge of an all-black company in the Quartermaster Corps specializing in salvage and repair. The company saw action on Okinawa and he left the army with the rank of captain, returning to the Detroit News as a copy writer on the rewrite desk. He also moonlighted as a writer and editor on the Michigan edition of the Daily Worker, the CPUSA’s flagship publication, appearing in its pages under a pseudonym. He and his wife were fervent supporters of Henry Wallace’s third party presidential run against President Truman in 1948.

After being subpoenaed to appear at a field hearing in Detroit being conducted by HUAC, Elliott was fired from his job. Following his testimony at the hearing (during which he took the Fifth Amendment on all questions relating to his communist activities), the Maraniss family moved to New York, where he briefly worked for a left-wing newspaper, the Daily Compass, before it folded. In early 1953, he went to work at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, from which he was fired after its editor learned of his communist past. Offered a chance to remain on the paper if he talked to the FBI, he refused.

Returning the family to Detroit, Elliott worked for two unhappy years as a salesman, then landed a job as an editor at a labor-sponsored newspaper in Iowa that folded after facing financial constraints. Finally he was hired by the Capital Times in Wisconsin, capping a string of living in five cities and eight homes in five years, being fired by two newspapers and having two others close down. The elder Maraniss went on to a distinguished career there, retiring as executive editor in 1983, having changed his politics “from radical to classical liberal, but not his values or belief in America,” his son writes.

CPUSA Self-Destructs

While Elliott was under FBI surveillance beginning in 1946, there apparently was little information in his FBI files about his activities, other than his work for the Party-controlled newspaper. The author says nothing about what his mother did. As Party members, the couple would normally have been expected to belong to a Party branch or cell, but there is no discussion of this aspect of their lives.

We know what was happening within the CPUSA at this time. Under pressure from the government and losing adherents, the Party hierarchy was responding by ratcheting up ideological bullying and weeding out “unreliable elements.” Between 1949 and 1953, the Party was engaged in a spasm of recriminations directed against members accused of white chauvinism—a campaign that historian Joseph Starobin, a one-time Party cadre, said “wracked the lives of tens of thousands.” Party members were reprimanded or purged for sins such as using words like “whitewash” or “black sheep,” or for serving fried chicken or watermelon at interracial picnics.

What we don’t know is, did this campaign ensnare the author’s parents (particularly since his father had commanded a unit of black troops)? Did it contribute to his father’s disillusion? We never learn—and maybe David Maraniss does not know.

There is also remarkably little about how being Jewish affected David’s father. His antifascism certainly played a large role in his allegiance to communism. But, there is virtually no discussion of the role of anti-Semitism. Mary was not Jewish; if the four Maraniss children had any perception of being Jewish, it is not mentioned. There are several references to attending events at the Jewish Cultural Center in Detroit, but these appear to be CPUSA events. More significantly, Elliott’s defenses of the Nazi-Soviet Pact take no account of the pact’s implications for European Jews. Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaign beginning in 1949, and culminating in denunciations of “rootless cosmopolitans,” the arrest and murder of Jewish intellectuals, the overtly anti-Semitic Slansky purge trials in Czechoslovakia, and the arrests of Jewish doctors accused of killing Soviet leaders—all were roiling Jewish communists from 1949 to 1953. Did any of it impinge on Elliott Maraniss? We never learn.

While the white chauvinism campaign and Soviet anti-Semitism go undiscussed—perhaps because Elliott Maraniss chose not to discuss them with his son—the author makes a common, but not insignificant, error: mischaracterization of the Spanish Civil War and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. He rightly emphasizes the bravery of the men (most of them communists) who volunteered to fight, while acknowledging the “brutishly unscrupulous and controlling Soviet advisors and communist hardliners” who dominated the Brigade’s leadership.

He also repeats one of the hoariest myths about the Brigade, which is that its members were labelled “premature anti-fascists” by the U.S. government. That they took great pride in this term, a sardonic pride given its purported origin, was true. But as John Haynes and I documented some years ago (“The Myth of Premature Antifascism,” New Criterion, September 2002), no government document using the term has ever turned up. The evidence we do have suggests it was first employed by members of the Brigade themselves. In any case, if people like David’s uncle Bob were premature anti-fascists, they were also premature pro-fascists, because from 1939 until the German invasion of the Soviet Union, they resolutely insisted that Britain and Nazi Germany were both imperialist powers with not a scintilla of difference between them.

They Said They Believed in Democracy, but It Wasn’t True

The author’s biggest blind spot, however, is his difficulty in coming to terms with why Americans despised and detested communists. After all, his parents were good people, whose main motives for joining the Communist Party were their opposition to fascism and American racism. They devoted their energies to trying to make American blacks full citizens; moreover, their friends risked (and some lost) their lives combatting real fascists in Spain. He recognizes that their allegiance to the Soviet Union and its brutal regime was morally repugnant. And yet he insists that his parents’ politics “did not diminish their patriotism.” His father “was a patriot in his own way” despite, for example, changing his mind about the justice of going to war against Hitler depending on where the Soviets were on this question.

David’s brother airily dismisses the idea that American Communists posed any threat to U.S. institutions or values, insisting that “nobody but the crazies thinks anymore that internal security was ever threatened” by the CPUSA.

Was the “Red Scare” just about some demagogues demonizing a handful of dissenters and rebels, and persuading significant numbers of Americans that communism was evil and communists were dangerous? There is no doubt that congressional committees and government authorities sometimes went overboard or acted irresponsibly. And many of the inquisitors were not nice people. (John Wood, the above-mentioned Democratic congressman from Georgia, had briefly belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. A deeper secret was that he had participated in the lynching of Leo Frank in Georgia in 1913, driving the car that took Frank’s body to the undertaker.) Many of the most vociferous opponents of communism who questioned the Americanism of the Maraniss family were staunch enemies of the American dream.

But, there were different kinds of anticommunism. The HUAC subcommittee that ensnared Elliott had come to Detroit to investigate communism in a large United Auto Workers local. Both George Crockett and Coleman Young had been ousted from positions in the UAW by the union leader Walter Reuther who, after the end of World War II, defeated the communists and their allies in a fierce factional struggle. David Maraniss attributes Reuther’s anticommunism to a pragmatic calculation that the labor movement needed to be anticommunist to appease Americans. Reuther, though, had once been a communist ally; like many others, he had learned through bitter experience that communists could not be trusted, used unscrupulous tactics, infiltrated the UAW and other organizations with secret members, and would jettison allies and revise their opinions whenever Soviet policy changed. Their public avowals about democracy were just that: for public consumption. They did not believe in it.

Even those with little personal experience in dealing with communists knew that the USSR had turned Central and Eastern European countries into Soviet satellites and murdered and repressed their opponents—just as they had after taking power in 1917. Millions of ethnic Americans with forebears abroad saw their old homelands suffering under communist rule—churches and synagogues destroyed, a free press crushed. Beginning in the late 1940s, they learned that Soviet espionage, using American communists, had stolen vital secrets enabling the USSR to build an atomic bomb. At the time Elliott Maraniss was called before HUAC, American troops were dying in a war being fought against communist troops. And the political party to which he belonged supported North Korea and falsely charged that America was using germ warfare.

David Maraniss believes his father was already harboring doubts about communism when he was called to testify. And Elliott Maraniss did not, unlike some HUAC witnesses, engage in verbal warfare with the congressmen either during or after he was questioned. But Elliott never publicly spoke about his communist beliefs or explained why he had come to reject them. Nor did he ever publicly admit that he was wrong. Some people who took the Fifth Amendment did so because they did not want to inform on old friends. The author thinks that a sense of loyalty motivated his father. That may well be right. But it does not excuse—although it may explain—the father’s allegiance for a number of years to a dangerous and evil doctrine. In some ways, Elliott Maraniss was a good American; for a portion of his life, however, he made a terrible mistake. That he corrected his error speaks well of him; that he refused to acknowledge it does not.