Bosch shows there is some measure of justice as well as love and forgiveness in L.A.

Decadence in Detroit

We live in a time of decadence. This is a hard truth to bear, so we tend to avoid it. Unfortunately, blindness to our problems is itself part of our decadence. Perhaps the first recovery of strength in this situation is to look at it with more clarity—to add to our moral habits the power to face ugly truths. More than our politics, our middlebrow entertainment has long dealt with this problem, by showing in dramatic form the major conflicts in American life and offering us protagonists who are immune to the gentle cowardice we call caution.

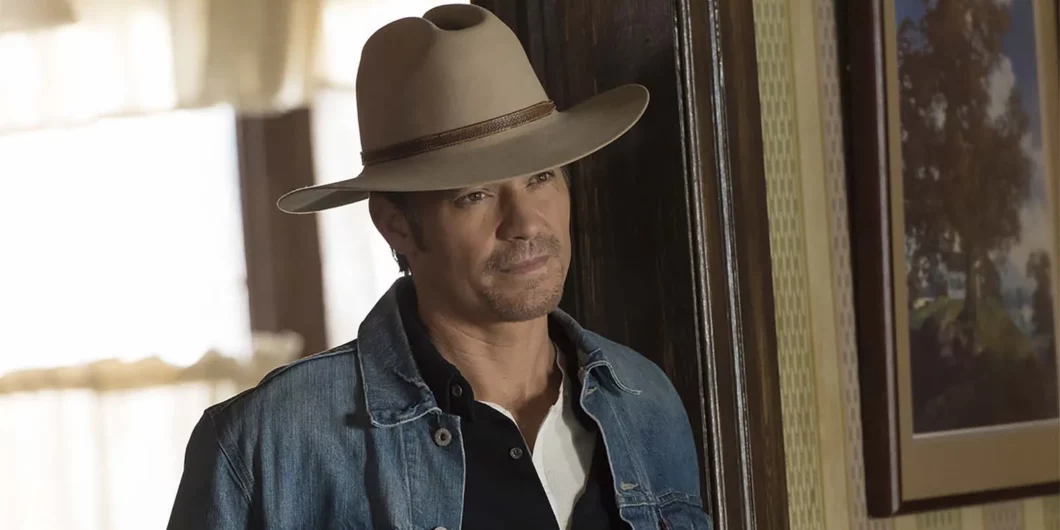

The most impressive such protagonist in recent times was Justified’s Raylan Givens (2010–2015, played by Timothy Olyphant, in the role of his career). He was a gun-slinging deputy US Marshal and the last man trying to stop the murderous mobs that have flooded America on account of drugs since the mid-century. That’s obviously a fantasy, you may even call it a fairy tale, but it does reveal the basic truth of our situation. Only men who care about justice can deal with the crazy mix of pleasure and pain that destroys weak people. Justice, they know, safeguards their personal integrity by allowing for the violent defense of life and property—and is ever more elusive in our times. America has decayed to the point that untold millions enslave themselves to drugs; some do it legally, since our laws have decayed alongside our mores. The man of justice distinguishes himself from such people by his self-respect and his rejection of debasing pleasures. He reminds us of an older, more virtuous America.

The most important symbol of that decadence is Detroit. In 60 years, it lost about two-thirds of its population, going from around 1.8 million to a bit more than 600,000 people. It was the wealthiest city in America on a per capita basis, an amazing democratic, even progressive achievement based on making cars. Back then, Detroit, the Motor City, got America moving, improving technology, and achieving new freedom. Now, it’s more of a ruin, as in Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino (2008). Nor was this decline gentle. It’s all about crime instead, especially related to drugs, political corruption, and one-party Democratic control. In the new series Justified: City Primeval, Raylan and Detroit collide.

The Lion in Winter

Raylan has always been a man out of time. Brought up in suffering in the hollers of Harlan County, Kentucky, with a vicious father and coal mining for his birthright, he’s a man whose path from suffering to nobility led him not to the future but back into America’s past, somewhat like John Wayne and the cowboys he played. Raylan is a man born for heroism in a time inimical to it, such that even the tiny federal law enforcement agency Raylan works for lacks glamour or power, the US Marshals. So Raylan’s crimefighting in Kentucky excites our great interest as viewers, but is also something the great American nation doesn’t care about, a paradox that drives Raylan’s development over the six seasons of the show.

Manliness is so interesting a virtue to consider in our times not just because it’s old-fashioned; it’s also wonderfully productive poetically, because it is the opposite of what our elites and the institutions they manage are about: safety, health, regulations, and bureaucracy. Manliness makes for tension and conflict, and might also allow us to think about what can be done in our situation, once we see it as a predicament. Wherever Raylan walks, resentment springs up like a poisonous weed, because he carries himself with confidence and is largely indifferent to the fantasies that animate ambitious status-seekers nowadays. Raylan was always a creature of the past and is therefore an insult to people who endlessly dream of the future; he reminds us that democracy is born of freedom, yet we live in a time of increasingly mandated and administered conformism, ideological, technological, and biological; his presence eventually forces us to confront the fact that we have somehow ended up in an upside-down world where supposedly genius and creativity are hypertrophic, but nobody in public life has any guts.

Justified is built on the tension between honor and profit, the latter connecting manliness to justice, the other connecting the rich and the poor.

Justified: City Primeval shows us the future has arrived and it is worse than we had been led to believe in the previous series. We begin in the Everglades, where two criminals in a pickup truck, black and white, crash into Raylan’s sedan and run him off the road before they threaten him with a gun and suggest they might rape his teenage daughter. Raylan arrests them, but then the court system in Detroit drops the charges out of resentment. Raylan is white, as is the prosecutor; one of the defendants, a repeat offender, his lawyer, and the judge are all black; and black and white no longer obey the same justice system, nor live in the same America.

The show then reveals that the judge is part of Detroit’s political corruption and the defense lawyer is involved with murderers and other criminals. The opening episode thus comes shockingly close to the truths that respectable Americans cannot face regarding crime and the unpredicted, apparently unstoppable resurgence in murders in recent years. City Primeval continues the Justified habit of rejecting our entertainment’s usual mix of cowardice and cynicism. Justified has some connection with the ugly truth about violence and the law, and why the law can neither be progressive nor like a business Republicans might want but merely another job, with a bit of killing here and there. Through harshness, Justified reminds Americans that they love justice and cannot stand by and see it betrayed, and asks, is that piety still alive in us?

Country and Western, Rhythm and Blues

The show’s ambition is hard to believe, since almost nothing in our entertainment puts black and white together, as though the culture isn’t shared. Think of music. Starting in the mid-century, American music was defined by rock. But older people like Johnny Cash and Ray Charles would play the same songs, because they had a similar way of life. Rock music is now dead and yet we still see black and white music: rap and country. Justified from the beginning featured country-rap songs, starting with its opening theme, reclaiming the shared culture. American music isn’t much these days, but our elites still revile the past when there was a shared culture.

Country singer Luke Combs recently covered Tracy Chapman’s Fast car, the song became a hit again. The popular appreciation for the song occasioned hysterical progressive performance in the Washington Post, because Combs is white and Chapman black. But the country cover is about class solidarity across racial lines, the mutual recognition of suffering as part of human nature among the poor, and an all-American habit of turning sorrow into music. Chapman approved the cover and was not interviewed by the Post. Elite hatred of country music endures—as does the reaction to it, which sends audiences to watch Justified. This is the music Raylan Givens listens to, the only expression the show allows of his suffering, perhaps a necessity for a manly man who cannot expect honors. The music tells truths we cannot otherwise bear to hear. Yet America does want some version of manly justice, as seen by the most successful song this week, country singer’s Jason Aldean, Try that in a small town, a weaker version of what Merle Haggard’s sentiment in Okie from Muskogee.

Most of the pairs of black and white characters in City Primeval are unhappy. The black judge has a white assistant who turns out to be an informant in a corruption case against him. The judge also has other unhappy entanglements with white people. Then there’s the white antagonist, who has a black coconspirator who fears the madman. Then there’s Raylan, who gets a black partner while he’s compelled to work in Detroit, investigating some crimes related to the judge until he runs into this terrifying new antagonist, yet another one of the fascinating murderers of the Justified series. “Race relations,” the strange euphemism we use for the failure to bring about justice or even care about the law, aren’t what they were, or were thought to be. The judge rants about racism from the bench, since he believes he’s untouchable.

Now, let’s talk about Raylan’s antagonist. Clement Mansell is a charming murderer, robber, and assorted criminal. A character we’ve seen more and more in our entertainments, part of the liberation the progressives have offered America since the ‘60s. He’d be called a sociopath or psychopath nowadays. Why? Because the jargon made people feel superior—scientific types who use Greek neologisms, believe themselves to be value-neutral rationalists, and therefore beyond good and evil. But in the old Greek way of speaking, he would be called a tyrannic soul. A man who has noticed that the world of progress is lawless and decided to live up to that ideal, putting himself in the place of God. He goes around with a tape of Seven Nation Army, the last guitar hero song in rock music, by Detroit artist Jack White, the last guitar hero.

Again, this antagonism might make Justified seem like a fairy tale, where the good guy fights the bad guy and saves the day. Charming criminals murdering left and right in fast cars aren’t a part of American life, there just isn’t enough manliness for that. Perhaps progress must continuously dig up the past, as with Southern generals or their horses, to have enemies to fight. But perhaps the problem is real. Mansell should be interpreted as the result of an America where elites treat honorable men like Raylan with contempt. Creatures of dishonor like Andrew Tate (recently interviewed by Tucker Carlson) emerge in the progressive world; like Tate, Mansell is a part-time pimp and brags about his lawless behavior, because he identifies Progress with the opinion that crime pays, and thinks he himself is an example of it.

Justified is not a simple-minded show. It is built on the tension between honor and profit, the one connecting manliness to justice, the other connecting the rich and the poor. Public life does not involve an education concerning the virtues, so that has become a secret of private life divulged in some of our entertainments. City Primeval continues the exploration of Raylan’s attempt to defend his integrity in a corrupt society where criminal law is no longer understood as the core demand of justice. It adds to his desperate attempt to make sure that his teenage daughter understands him and respects him, although America doesn’t. Two episodes into the season, I recommend it—it’s the best thing on TV now!