Understanding De-Industrialization means looking at indirect causes like the place of the U.S. Dollar in the global economy.

Industrial Policy Mythology Confronts Economic Reality

If prizes in policy debates were given out for persistence, those advocating for more widespread use of industrial policy in America would be first in line. No matter how many times it is pointed out that they don’t understand the nature and workings of comparative advantage; or avoid acknowledging how industrial policy fosters rampant cronyism and corruption; or highlight what they consider examples of countries in which industrial policy has been employed successfully (only to have it demonstrated that it didn’t quite work out the way they suggested), they don’t give up.

Perhaps, some of them might acknowledge, the selective use of industrial policy in Japan or the EU, or its extensive deployment in nations as different as Argentina and India (not to mention most African and Middle-Eastern countries) generally failed to produce the anticipated results. But, the refrain goes, what about some of the East Asian Tiger countries? Aren’t they proof that, when devised and implemented by wise governments guided by even cleverer experts, industrial policy can work?

Alas, the gap between myth and reality is just as evident in these cases. Many East Asian governments have certainly engaged in industrial policy. By this, I mean the state seeking to address apparent failures on the market’s part to produce particular commercial outcomes by intervening in specific economic sectors via means such as subsidies, preferential tax treatment, outright capital grants, loans at below-market interest rates, direct and indirect support for business R&D, joint public-private enterprises, or special regulatory measures.

There is, however, a wealth of evidence indicating that these policies produced similarly pedestrian outcomes in these countries. As for the Tigers, what primarily took them from the status of economic backwaters to first-world economies was economic liberalization and especially trade openness—not experts with great confidence in their own ability to foresee and generate specific economic outcomes via state intervention.

Even the most devoted industrial policy advocates hesitate to present two of the Tigers, Singapore and Hong Kong, as industrial policy successes. They do nevertheless regard South Korea and Taiwan’s postwar histories as demonstrating why industrial policy should play a major role in economic life. The facts, however, indicate a much more complicated and different story.

From War-Torn Wreck to Economic Powerhouse

At the end of World War II, Western policymakers pursued a contradictory agenda for the global economy. On the one hand, they encouraged the dismantling of tariffs between Western countries which, they held, had reflected and fueled aggressively nationalist impulses in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet many also endorsed protectionism and import-substitution policies by developing countries.

The logic, as articulated by the Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch, was that what he called peripheral nations were disadvantaged vis-à-vis Western economies due to the adverse terms of international trade, as Prebisch and others understood them, facing poorer countries. It followed, they argued, that developing nations should not only limit foreign investment and restrict trade with developed economies to facilitate the growth of domestic industrial sectors. These nations, they insisted, should also use industrial policy extensively to bolster the type of development that markets, it was contended, would not deliver.

The ruin that was South Korea in the early-1950s appeared to such policymakers as exemplifying the need for such measures. Beginning in 1954 and until about 1963, Korea’s government focused upon import-substitution industrialization policies designed to promote reconstruction. This was accompanied by high tariffs on those imports that had domestic substitutes.

As the Indian economist Arvind Panagariya points out, Korea started getting back on its feet during these years. He adds, however, that economic growth in Korea only began taking off between 1963 and 1973 following a decisive shift towards export-orientated development and trade openness. Korea also decided not to increase import substitution for products for which it lacked comparative advantage. Instead, Panagariya writes, Korean businesses “chose to expand the output of labor-intensive products in which [they] had comparative advantage and sell them in the export markets.”

During these years, targeting of selected industries by the government was quite limited. So too was infant industry promotion (a perennial favorite of industrial policy enthusiasts). The state did offer export incentives for Korean businesses. These incentives, however, were not particularly skewed towards trying to bolster one economic sector’s development over others. In that sense, they had a more-or-less neutral impact upon the Korean economy’s sectoral development—which is the opposite of what industrial policy seeks to realize.

Industrial policy assumed a larger place in Korea’s economy in the mid-1970s. The causes included a desire to put a lid on a growing trade-deficit by restraining imports, and the decision to respond to reductions in American military forces in the Korean Peninsula by fostering strategic industries through what was called the Heavy-Chemical Industry (HCI) drive. The primary vehicle for this endeavor was the government directing state-owned banks to make loans at below-market interest rates to such industries, accompanied by some backtracking on trade liberalization.

Korea’s turn towards industrial policy in this period does not appear to have produced spectacular results. Economic growth during this period—whether in terms of GDP, trade, employment, manufacturing output, or exports in goods and services—was actually lower than what had been realized in the 1960s. Certainly, there was growth in particular capital-intensive industries targeted by the HCI drive. But their performance was also generally poor, at least in terms of Total Factor Productivity growth.

These results may help explain why Korea’s drift towards industrial policy was reversed, beginning in the late-1970s. Not long before President Park Chung-Hee’s assassination in 1979, his government began tightening fiscal and monetary policy, thereby reducing the state’s capacity to engage in the targeted direction of credit at the HCI sector. By the early 1980s, Panagariya illustrates, a program of phased tariff reductions had been introduced and the number of industries labelled “strategic” was reduced. The policy of preferential interest rates for strategic industries and exporters was abolished in 1982. Foreign direct investment was liberalized, not least as a way to speed up private sector technological development. Also liberalized was the financial sector. Not only was it opened up to foreign direct investment, but many state-owned banks were privatized. Regulations were eased to allow the development and use of more sophisticated financial instruments.

The overall result was a return to high growth throughout Korea’s economy. Interestingly, some HCI industries thrived in these new conditions. Advocates of industrial policy regard this as vindicating their position. But, Panagariya notes, it was the disciplines unleashed by greater domestic and foreign competition and the withdrawal of government support which forced these industries to either get efficient or die. They chose the former.

Concerning the claim that the growth spurred by these industries would never have existed in the first place without industrial policy, the short answer is that there is no way of knowing this. This is indicative of a more general intellectual problem with industrial policy: the difficulty of identifying any meaningful causality between industrial policy and economic growth. As observed by the authors of the famous 1993 World Bank report on the East Asian economic miracle, “It is very difficult to establish statistical links between growth and a specific intervention and even more difficult to establish causality. Because we cannot know what would have happened in the absence of a specific [industrial] policy, it is very difficult to test whether interventions increased growth rates.” By contrast, the evidence linking economic liberalization to substantive increases in economic growth and poverty reduction is simply overwhelming.

From Rump-State to Dynamic Economy

Taiwan faced equally unappetizing economic conditions when Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang military retreated across the Taiwan Strait in 1949. The island’s inflation rate that year was 500 percent, while its trade volume was just 25 percent of what it had been during Japanese occupation in the 1930s. Taiwan also had to absorb a huge influx of refugees from mainland China, and was dependent on American aid.

Taiwan’s masters initially followed paths similar to those pursued by Korea. Alongside a major land reform, the Kuomintang government adopted an import-substitution approach to trade characterized by high tariffs and import quotas. The Taiwan Production Board oversaw the extensive use of industrial policy, especially through preferential loan-treatment in sectors ranging from textiles to cement and plastics.

The problem is that the more you rely upon import substitution policies, the more you start migrating much of the economy into sectors where you don’t enjoy comparative advantage. In the mid-1950s, key Taiwanese officials and their American advisors recognized that Taiwan could not keep going down this path. Hence in the late-1950s, decisions were made that re-orientated Taiwan’s economy towards competition and trade openness by, among other things, liberalizing imports and foreign investment rules as well as beginning a process of steadily removing export controls and gradually giving more and more exporters what amounted to a free trade status. As in Korea’s case, growth in Taiwan took off.

Taiwanese governments continued to intervene in much of the economy until the 1970s. But the general direction of Taiwan’s economy from 1958 onwards was away from industrial policy and tariffs and towards increasing integration into global markets. Like Korea, Taiwan underwent a limited return to interventionist policies in the mid-1970s, but, again, like Korea, this did not last.

Those Americans presently trying to persuade senators and other likely presidential contenders of industrial policy’s merits by parading whatever happens to be their latest poster-child continue to have trouble reconciling important parts of their position with the evidence.

Throughout the 1980s, Taiwan’s economy was opened ever further to trade. The government also embarked on an extensive privatization of state-owned enterprises and banks. Foreign direct investment was further liberalized. All these measures diminished the influence of technocrats wedded to government-centric approaches to the economy. Today, Taiwan is ranked as the world’s sixth freest economy in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom.

Like all economies, those of Taiwan and Korea are not problem-free. Lingering corruption remains a significant challenge in both nations. Also looming are all the economic difficulties associated with aging populations.

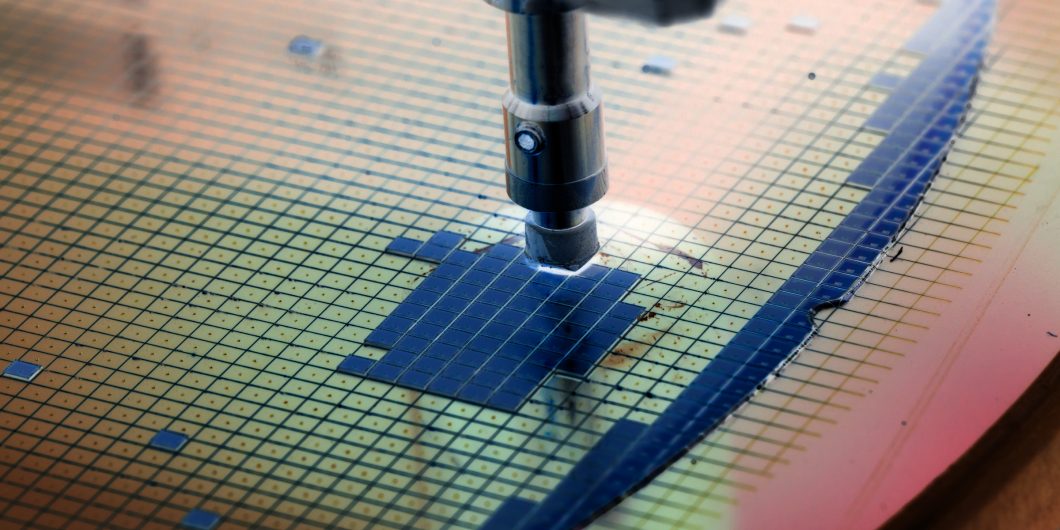

Nor are Korea and Taiwan’s economies completely devoid of industrial policy. Some argue that industrial policy explains why Taiwan presently dominates the world’s semiconductor market. But even here, the story turns out to be far more complicated than industrial policy advocates portray it.

What Cause? Which Effect?

In 1974, an expatriate Chinese engineer working for RCA Corporation (a publically-listed American electronics company established as an independent business in 1932 as part of an anti-trust settlement by its four owners, AT&T Corporation, General Electric, United Fruit Company, and Westinghouse) persuaded Taiwan’s economics minister that Taiwan would be well-advised to get into the semiconductor business.

Two years later, Taiwan’s government entered into and paid for a technology transfer agreement with RCA. As part of the deal, engineers from the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) were sent to America for training. A non-profit organization, ITRI was never part of the government. Nor were its workers ever government employees. Though initially given some government seed money, state funding soon ceased and ITRI quickly shifted to deriving its income from private contracts.

After they returned from their training in America, these ITRI engineers worked on semiconductor technology until their project was spun off in 1980 as Taiwan’s first private integrated circuit company, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC). While it too received some initial state funding, the government stayed out of management decisions and soon sold all its shares. UMC was listed on Taiwan’s Stock Exchange in 1983 and the New York Stock Exchange in 2000.

A similar story characterizes the emergence of the biggest player on the world’s semiconductor block, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Another ITRI spin-off, it was established with some initial government funding and private capital as a private business in 1987, before being listed on Taiwan’s Stock Exchange in 1993. It became the first Taiwanese company listed on the New York Stock Exchange four years later. Today, TSMC’s majority shareholders are foreign investors.

So: consider the following facts. Yes, the Taiwanese government did organize the initial technology transfer. Yet the idea to do so came from someone living in America working for an American private business and who saw the technology’s potential—not a Taiwanese technocrat. Yes, the ITRI, UMC, and USMC received some government seed-money. But it’s also the case that the ITRI quickly became a privately-funded independent institute and that semiconductor technology acquired its commercial legs through privately-owned companies like UMC and ISMC. They took the risks of raising the bulk of domestic private capital (not to mention all the foreign capital), hiring key personnel (many from American businesses), and competing in the domestic and global marketplace—not the Taiwanese economics ministry or a government-owned enterprise.

It’s worth mentioning in this context that while the Taiwanese government underwrote about 44 percent of total spending on R&D in 1990, that had dropped to 6.5 percent as early as 1999. Today, the primary funding for semiconductor R&D in Taiwan comes overwhelmingly from the private sector. Indeed, almost 85 percent of overall R&D development in Taiwan in 2020 was funded by the private sector, thus dwarfing the combined contribution of independent institutes, universities, and the government. This fits the overall pattern of economic liberalization and the move away from intervention that have characterized Taiwan’s last forty years of economic development.

No Straight Line

The Taiwanese story fits the general pattern for numerous projects that industrial policy advocates have claimed as triumphs for intervention. Take, for example, the Internet. Its predecessor, the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), was created by a US Defense Department agency as a military-networking device used by government agencies and university researchers. But as Adam Thierer illustrates in his book Permissionless Innovation (2014), it was not until the Clinton Administration permitted open market commercialization of this technology that the modern Internet became possible. The same administration consciously adopted an anti-industrial policy approach to this area.

Thus while ARPANET did have unintended spillover effects, it is a stretch to say that the decision to create it led directly to the Internet, let alone to claim the Internet as an example of successful industrial policy. There is no straight line between this government project’s development of particular pieces of technology and the Internet’s emergence. The same is true of the iPhone’s development and state-sponsored science projects.

All this suggests that those Americans presently trying to persuade senators and other likely presidential contenders of industrial policy’s merits by parading whatever happens to be their latest poster-child continue to have trouble reconciling important parts of their position with the evidence. Whether it is explaining East Asian economic successes or the rise of Taiwanese semiconductor companies, industrial policy explanations constantly come up short. Pointing this out isn’t an instance of “market fundamentalism.” It’s simply a reminder that facts, however complicated, ought to matter.