Baltimoreans would have a better chance of rescuing their city if officials weren’t bent on property tax hikes and outlandish assertions of eminent domain.

Rediscovering the “Inner Check”

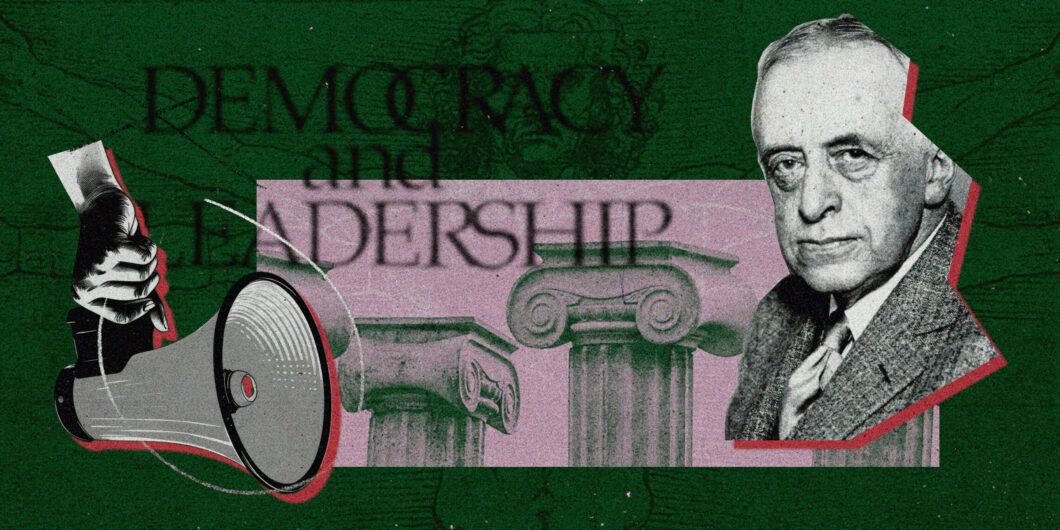

It would be challenging to name an American literary and social critic about whom more nonsense has been written than Irving Babbitt (1865–1933). Babbitt, a classically trained professor of French and comparative literature at Harvard University, was, along with his best friend and intellectual ally Paul Elmer More (1864–1937), one of the founding fathers of the New Humanism, an informal movement that attracted widespread attention in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The sudden and unanticipated fame accorded to the New Humanism in both the United States and Europe—eventually even in China—encouraged numerous culture warriors to weigh in on Babbitt, More, and their epigones. Their estimations, seemingly composed with the rapidity required of daily newspapers and weekly magazines, contained all manner of infelicities and distortions. Despite the manifest inaccuracies in the polemics against the New Humanism, Babbitt’s reputation has somehow never fully recovered from the raucous debates about his work. Through the years, writers as various as Allen Tate, Edmund Wilson, R. P. Blackmur, Alfred Kazin, and Edward Said have pilloried Babbitt, and though their critiques leave much to be desired, their collective efforts appear to have denied him the lofty reputation that he deserves.

To be sure, Babbitt’s astoundingly capacious intellect and meandering prose style contributed to misunderstandings about his ideas. Babbitt’s learnedness was legendary even in the halls of Harvard. In March of 1931, for example, Time magazine reported on a gambling pool established by students in Babbitt’s Comparative Literature 11 course, according to which participants would place wagers based on the (large) number of authors to whom Babbitt would refer in a lecture. One day, Time noted, Babbitt “set a record: 73 quotations, from writers so various as St. Paul, Confucius, Dante, [and] Walter Lippmann.” A lifelong critic of triflingly minute research, Babbitt refused to reduce his writings to the diktats of professionalized scholarship. Especially for the narrowly trained academics of his (and our) era, Babbitt’s broad learning could leave critics feeling out of their depth.

Despite his impressive intellectual gifts, Babbitt—who, according to many of his friends and former students, was naturally more of a talker than a writer—had difficulty envisioning readers who hadn’t accrued his vast knowledge. Accordingly, his books do not proceed in a typical systematic fashion, scaffolding arguments in logical sequences to maximize their intelligibility. Instead, readers must muddle through Babbitt’s sprawling works to cobble together the basics of his arguments. Despite excelling at providing punchy, often humorous, phrases and quotable quips, Babbitt is a demanding author.

Given the stumbling blocks that face all who approach Babbitt’s prose, Allen Mendenhall should be praised for providing a concise and thoughtful examination of Democracy and Leadership, Babbitt’s lone book-length contribution to political theory. Although I have some disagreements with Mendenhall’s analysis (more on this anon), he’s the sort of interlocutor whom Babbitt deserves (but has only seldom received). In fact, Mendenhall’s essay gives us a sense of why Babbitt’s output—despite its manifest challenges—continues to deserve a wide readership today.

Contrary to decades of cavalier conclusions about Babbitt’s religious views, it is clear that he did not consider the New Humanism to be inimical to faith.

It is among the strengths of Mendenhall’s essay that it shares Babbitt’s sense of urgency and relates Democracy and Leadership to our current political moment. It may seem churlish to note reservations about an essay that provides so much with which to assent, but I hope the analysis to follow will help flesh out Babbitt’s approach to political theory and the human predicament.

Early in his piece, Mendenhall provides a few concepts he deems integral to Babbitt’s thought. Absent is the term most essential to the New Humanism’s brand of ethical dualism: the inner check. This concept, which Babbitt also called the “higher will” and (in a riposte to the French philosopher Henri Bergson) the frein vital, is central to Babbitt’s definition of humanism and to his all-important critique of what he calls “sentimental” and “scientific” naturalism. An inability to grasp Babbitt’s meaning on this point and to recognize its great importance has incapacitated many of his critics.

In Rousseau and Romanticism (1919), the monograph he composed directly before Democracy and Leadership, Babbitt describes the inner check thus:

Like all the great Greeks, Aristotle recognizes that man is the creature of two laws: he has an ordinary or natural self of impulse and desire and a human self that is known practically as a power of control over impulse and desire. If man is to become human he must not let impulse and desire run wild, but must oppose to everything excessive in his ordinary self, whether in thought or deed or emotion, the law of measure.

According to Babbitt, who spied an affirmation of the inner check in traditions as disparate as Greek philosophy, Hinduism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Christianity, people must engage their “human self”—their internal power of control—to affirm those impulses conducive to respectful and civilized life and to quash those that are selfish and destructive. Babbitt views this ordering force as transcending subjectivity. Always ecumenical regarding the ultimate questions, he sees this special type of will as in some way recognized by all the higher world religions and ethical systems. Although representing a positive purpose, this will is felt, with reference to impulses that are destructive of goodness in the world, as a “will to refrain,” a check. This higher will in man is, according to Babbitt, what Christianity calls “Grace.”

Thanks to the unfortunate dominance of naturalism—the rejection of a universal moral imperative—in his day, Babbitt thought, human beings typically eschewed this “civil war in the cave,” preferring, as the Rousseauian sentimentalist counseled, to revel in dreamy impulse or, as the Baconian utilitarian advised, to gain increasing mastery over the natural world. Although not unreceptive to the benefits of the romantic movement and the scientific project, Babbitt recognized that the avoidance of the internal struggle between good and evil—what Babbitt in Democracy and Leadership called “the old dualism”—would court personal misery and civilizational chaos. “The old dualism put the conflict between good and evil in the breast of the individual,” Babbitt wrote, “with evil so predominant since the Fall that it behooves man to be humble; with Rousseau, this conflict is transferred from the individual to society.” The scientific naturalist analogously places the emphasis on manipulation of the external world.

Babbitt’s perspective on ethics pertains directly to his approach to political theory. Readers of Mendenhall’s essay may conclude that Babbitt was somehow anti-democratic, a fusty aristocrat appalled by the great unwashed. This view—common among the culture warriors who have attacked Babbitt—is mistaken. Democracy has no single definition. As the political philosopher Claes G. Ryn has persuasively argued, Babbitt opposes a certain approach to popular rule while supporting another. In his book Democracy and the Ethical Life (1978), for example, Ryn, drawing on Babbitt, makes a distinction between two very different forms of popular government: majoritarian/plebiscitary democracy and constitutional/representative democracy.

Babbitt’s Democracy and Leadership provides a critique of the former and support for the latter. His rationale for this position relates to the concept of the inner check: in Rousseauistic style, plebiscitary democracy relies on the instantaneous impulses of the people, whereas constitutional democracy supplies needed checks on power—including popular power. The checks and balances key to the US Constitution, then, are a kind of governmental corollary to a person’s frein vital. Babbitt considered plebiscitary democracy dangerous—and ultimately imperialistic—because it stemmed from the sort of unrealistic view of human nature he attributed to sentimental naturalism.

Other common misconceptions about Babbitt’s ideas surround his approach to religion and how it relates to humanism. Babbitt arguably caused some such misimpressions; non-confessional in religion and an admirer of aspects of Buddhism, he was often cagey in his books and essays about the relationship between his experiential approach to the ultimate questions and doctrinally based notions of faith. Even Paul Elmer More, upon his return to Christianity in the late 1910s, criticized Babbitt for his supposed vagueness about the precise meaning of the “superhuman” and the “supernatural.”

Yet Mendenhall errs when he states that “Babbitt’s humanism embraces agency and will whereas the naturalistic and religious modes suffer from determinism or fatalism.” Here again Ryn—for decades Babbitt’s most reliable and incisive interpreter—can help us avoid confusion. In a piece called “Irving Babbitt and the Christians,” Ryn notes, “In formulating the idea of the inner check, or higher will, Babbitt is not trying to talk Christians out of their beliefs. He is addressing all of those in the modern world who are not willing to accept ethical and religious truth on the authority of inherited dogmas. To these modern skeptics, he argues, not that traditional beliefs are wrong, but that ethical and religious life do not stand and fall with Church authority. They have an experiential foundation.”

Although Babbitt believed that religious modes of thought could suffer from determinism and fatalism, this was by no means a foregone conclusion. In fact, throughout Democracy and Leadership, Babbitt proves supportive of certain Christian, Buddhist, and even Islamic conceptions of faith. Babbitt made his support for religion even clearer in his contribution to Norman Foerster’s edited collection Humanism and America (1930): “For my own part,” he wrote, “I range myself unhesitatingly on the side of the supernaturalists. Though I see no evidence that humanism is necessarily ineffective apart from dogmatic and revealed religion, there is, as it seems to me, evidence that it gains immensely in effectiveness when it has a background in religious insight.” Contrary to decades of cavalier conclusions about Babbitt’s religious views, it is clear that he did not consider the New Humanism to be inimical to faith. His approach to the ultimate questions was, on the contrary, an attempt to restate and recover in experiential terms moral-spiritual insights that were being lost under the sway of scientific and sentimental naturalism.

I wholeheartedly agree with Mendenhall when he concludes that Babbitt’s “beliefs and convictions” still “remain relevant. And we are mistaken and misguided to ignore them.” We may hope that the 100th anniversary of Democracy and Leadership will encourage readers to examine Babbitt’s ideas anew.