Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh has many years on the bench and has demonstrated himself to be a smart originalist.

We Should Have Listened to Irving Babbitt

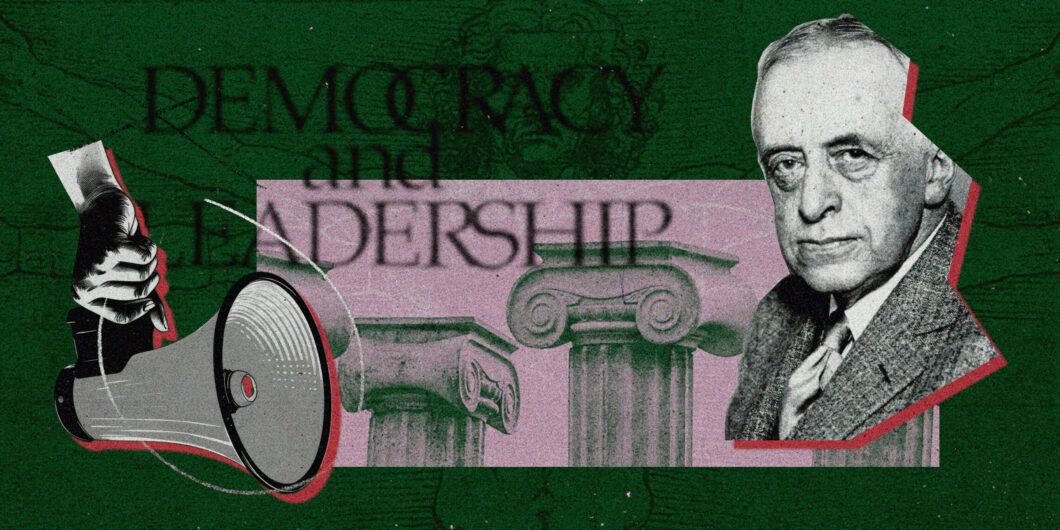

My task is to review Irving Babbitt’s delightfully ponderous Democracy and Leadership, published a century ago this year, and to assess its relevance to present circumstances. Despite the proliferation of degrees in leadership and schools of leadership, there’s no consensus regarding what leadership is or how to achieve it.

Babbitt had an idea involving a few key concepts: naturalism, imagination, standards, progress, and humility. One must understand Babbitt’s interpretation of these to appreciate his outlook on democracy and leadership.

To that end, I’ve arranged my analysis by successive propositions even though Babbitt didn’t do so himself. Nor did he present his case logically or sequentially but rather as loosely organized essays with scattered insights, prioritizing style and sound over coherence. My approach spares readers the labor, however joyous, necessary to apprehend Babbitt’s meandering ruminations but is no substitute for the text itself.

Now on with it.

The Inadequacy of Naturalism

Babbitt’s first proposition is that naturalism is inadequate because of its flawed idealism and misplaced faith in progress.

Babbitt frames human experience as tripartite: “The view of life that prevails at any particular time or among any particular people will be found on close inspection, to be either predominantly naturalistic, or humanistic, or religious.” He expends effort distinguishing the first two, principally because the religious view no longer controls. The “older religious control has been giving way for several centuries,” theocratic government is rare, and the inner self as against external authority is the chief source of most going philosophies.

Pursuing humanism (“I aim to be a humanist”), Babbitt opposed naturalism while joining the naturalist rebuff “of outer authority in favor of the immediate and experiential.” Babbitt’s humanism embraces agency and will whereas the naturalistic and religious modes suffer from determinism or fatalism. “My own attitude,” Babbitt explains, “is one of extreme unfriendliness to every possible philosophy … which tends to make a man the puppet of God, or … the puppet of nature.”

Not eager to define terms, perhaps assuming readers’ familiarity with his earlier work, Babbitt depicts two forms of naturalism, the Baconian and the Rousseauian. Overlook, please, the ultimate incompatibility between Francis Bacon and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, namely their accounts of science and humanity’s relationship to nature; for Babbitt is less interested in their general consistency than in their mutually reinforcing portrayal of progress. In Babbitt’s telling, Rousseau revises and complements Bacon, setting naturalism on a new course.

Baconian naturalism is mechanistic, empirical, rational, and reductive—a product of scientism with utopian tendencies (think The New Atlantis). Exemplified by the French Revolution, the naturalism of Rousseau (“first among the theorists of radical democracy”) is abstract, idealistic, romantic, emancipatory, egalitarian, and emotional—a product of sentimentalism. Rousseau’s emphasis on “fraternity” and “universal brotherhood” is, Babbitt says, “a sentimental dream.” Bacon imbued naturalism with reason; Rousseau, with enthusiasm and excitement. “Rousseau gave to naturalism the driving power it still lacked,” Babbitt opines.

Against the idyllic imagination of Rousseau, “who is straining out toward the absolute and unlimited,” Babbitt championed Burke’s moral imagination, which is “organic” and “historical.”

Babbitt concedes that the “naturalistic effort during the past century or more has resulted in an immense and bewildering peripheral enrichment of life.” However, he maintains that “no amount of peripheral enrichment of life can atone for any lack of center.”

The religious mode provided a center: an integrating, centripetal force for civilization. But, for moderns, religion no longer quickens hearts or captures minds, at least not to the degree that it did epochs ago. Nor does naturalism with its glorification of progress supply an indispensable core of ordering principles. Babbitt asks “Why should men progress unless it can be shown that they are progressing toward civilization?” Absent the religious mode, only humanism can establish the necessary center, the assimilating principles requisite to civilization.

The Inner Life

Babbitt’s second proposition is that humanism properly understood involves the “inner life.”

Babbitt was an individualist who saw “the significant struggle” not as between individualism and traditionalists, or individualists and collectivists, but as between “the sound and the unsound individualist.” Babbitt avers, “To be a sound individualist, one needs, as I take it, to regain one’s hold on the truths of the inner life, even though breaking more or less completely with the past.”

A word of caution: breaking with the past is not disregarding or discounting history. It evokes instead Kant’s motto for the Enlightenment: Have courage to use your own understanding. The admonition is against uncritical trust in preceding authority. “In direct ratio,” according to Babbitt, “to the completeness of one’s break with the past must be the keenness of one’s discrimination.” Therefore, Babbitt renounced fashionable philosophies because he detected no truth in them. He consulted, instead, the “wisdom of the ages,” which, of course, covers the past. In Babbitt’s paradigm, attention to the contextual, situated, nested, and embedded nature of ideas forestalls rigid ideology with its simplification of complexities and its desire to impose static dogma on resistant communities.

The “inner life” is essential to Babbitt’s version of humanism because it affords opportunities to discern truth. Babbitt describes it as “the recognition in some form or other of a force in man that moves in an opposite direction from the outer impressions and expansive desires that together make up his ordinary or temperamental self.” Truth exists independently of the emotions and passions stirred by externalities, so one turns inward, to the conscientious self, to separate fact from feeling.

Ascertaining truth is profoundly personal. It demands tenacity and erudition, which frustrate the indolent person: “When an intellectually and spiritually indolent person has to choose between two conflicting views he often decides to ‘split the difference’ between them; but he may be splitting the difference between truth and error, or between two errors. In any case, he must dispose of the question of truth or error before he can properly begin to mediate at all.”

To discriminate while setting higher standards requires effort and tenacity—and moderation. When Babbitt propounds that “the essence of humanism is moderation,” he doesn’t eschew extremes or absolutes. He means that the humanist suspends judgment until he has resolved complexities at the end of rigorous inquiry. “A man’s moderation,” he mused, “is measured by his success in mediating between some sound general principle and the infinitely various and shifting circumstances of actual life.” Moderation, then, rates selectivity above inclusivity, mediating “between the constant and the variable factors in the human experience.”

The Moral Imagination

Babbitt’s third proposition is that the moral imagination of Edmund Burke is superior to the idyllic imagination of Rousseau because it requires standards grounded in concrete reality and lived experience rather than abstraction or rationalism.

“One may,” Babbitt submits, “regard the battle that has been in progress since the end of the eighteenth century as … between the spirit of Burke and that of Rousseau.” Rousseau represents the idyllic imagination whereas Burke represents the moral imagination. The former projects “the myth of natural goodness,” “emancipation of feeling,” “expansive” or “explosive” emotionalism, and yearning for a “pastoral” age that never existed. Messy phenomenal reality can never live up to idealized, fantastic pasts. Knowing this, the “agitator” exploits nostalgia to facilitate the “destruction of the existing social order.”

Against the idyllic imagination of Rousseau, “who is straining out toward the absolute and unlimited,” Babbitt championed Burke’s moral imagination, which is “organic” and “historical.” Burke, wrote Babbitt, was an individualist humanist who fostered individual liberty grounded in prescription. The moral imagination accounts for “accumulated experience,” “habits,” and “usages.” Standards, facts, and experience temper its creativity.

Burke embodies “the spirit of moderation” and estimates people not by “hereditary rank” but “personal achievement.” By contrast, judging “men by their social grouping rather than by their personal merits and demerits … has … been implicit in the logic of this movement from the French to the Russian Revolution.” Burke exalts awe and reverence, counseling incremental rather than radical or revolutionary change to ensure continuity not for its own sake but to nurture “an ethical center,” i.e., “a standard with reference to which the individual may set bounds to the lawless expansion of his natural self.”

The moral imagination equilibrates between “the taking on of inner control and the throwing off of outer control.” Recurrence to the moral imagination enables free government, a balance between liberty and restraint: The more individuals in the aggregate demonstrate self-control and self-discipline, the less defense there is for coercive external controls.

“The Law of Humility”

Babbitt’s fourth proposition is that humility is a cardinal virtue that guides inquiry towards truth, reality, and facts rather than conceit, shams, or chimera.

Babbitt sums up his “whole point of view by saying that the only thing that finally counts in this world is a concentration, at once imaginative and discriminating, on the facts.” A posture of humility conduces fact-finding.

“Christian virtue in particular has its foundation in the law of humility,” said Babbitt, who insists that humanism must “put its ultimate emphasis on humility.” Humility is not an ideology or program but a disposition or mood that “decreased with the decline of traditional religion.” Humility signifies reservation and restraint. Its opposite is bravado, hubris, or arrogance, properties consonant with Rousseau’s “reinterpretation” of virtue as “a sentiment and even an intoxication.” These lead to imperialism, the readiness to impose ideals on others by might or violence. They precipitated the French Revolution, which “took on the character of a universal crusade,” as well as the Bolshevist Revolution, which “has been even more virulently imperialistic than French Jacobinism.”

Babbitt says we live “in a world that in certain important respects has gone wrong on first principles.” If that’s correct, then the way back to civilization is to train up new leaders attuned to the moral imagination and the inner life.

Babbitt’s perspective on humility implicates leadership. He remarks that “the true leader is the man of character, and the ultimate root of character is humility.” Contra egoist presumptions of total originality, humility prompts mimesis, i.e., recourse to tested ideas and trusted thinkers to erect higher standards, which generate an “abiding unity” amid “variety and change.” Channeling Confucius, Babbitt proclaims, “A man who looks up to the great traditional models and imitates them, becomes worthy of imitation in his turn. He must be thus rightly imitative if he is to be a true leader.”

Concrete historical antecedents supply the data necessary to differentiate true from false standards. Good leaders must acquire standards, and to do so requires the self-discipline of the moral imagination.

The Dangers of Majoritarianism

Babbitt’s fifth proposition is that democracy as pure majoritarianism is dangerous; a group of leaders will rule any society, no matter how democratic. Better for society if leaders embrace the moral imagination rather than the idyllic imagination, and if they cultivate an inner life at once creative and self-disciplined.

“A main purpose of my present argument,” Babbitt states, “is to show that genuine leaders, good or bad, there will always be, and that democracy becomes a menace to civilization when it seeks to evade this truth.” He spurned the idea that numerical majorities representing the general will should replace wise leadership. He argued that the quality of democracy, like other forms of government, depends upon the competence of its leaders and the quality of their vision.

Babbitt treated majoritarian democracy as an avoidable conceit, sham, or chimera. To the extent it accords equal validity to disparate tenets and opinions, it debases standards, harkening back to the homogenous “democratic fraternity” of Rousseau. Babbitt disparaged democracy for empowering majorities to override “natural” leaders. “From the point of view of civilization,” Babbitt elaborates, “it is of the highest moment that certain individuals should in every community be relieved from the necessity of working with their hands in order that they may engage in the higher forms of working and so qualify for leadership.”

Worried that “the aristocratic principle” would “give way to the egalitarian denial of the need for leadership,” he professes that hierarchy befits “every civilized society” as long as those at the top earn their spot. He hated laziness and idleness, but distinguished manual from intellectual labor, grading the latter on par with the former.

Conceptually, leadership presumes superiority: leaders cannot exist without followers. In a just, free society, leaders would possess superior character and discernment and not just a superior rank or station. These wise models would base decisions on facts and realities revealed over centuries of dialogue and debate, trial and error, and toilsome study. Society decays, however, when leaders mobilize people towards sham visions, chimeras, and conceits.

Babbitt says we live “in a world that in certain important respects has gone wrong on first principles.” If that’s correct, then the way back to civilization is to train up new leaders attuned to the moral imagination and the inner life. He underscored the need for leaders who grasp the truths revealed in history by avoiding idealism and sentimentalism. “Where there is no vision, we are told, the people perish,” Babbitt cautions, “but where there is sham vision, they perish even faster.”

The Question of Equality

A safe and circumspect closing would commend the uncontroversial aspects of Democracy and Leadership. But let’s get provocative, and ponder whether the marrow of our government, the cultural tissue of the United States of America, consists, in no small part, of shams, chimera, and conceits. Babbitt’s picture of Thomas Jefferson (whose “Epicureanism” Babbitt detested) and the Declaration of Independence (“which assumes that man has certain abstract rights”) implies that possibility.

We are two years from the United States Semiquincentennial of the Declaration. That commemoration will reveal the extent of Babbitt’s continued relevance insofar as two features of the Declaration—its natural-rights emphasis on human equality and popular sovereignty—clash with Babbitt’s humanism.

Consider, first, equality, the historically controversial proposition that “all men are created equal.” In 1842, Henry Clay stated that the Declaration held truth as an “abstract” or “fundamental” principle but that “in no society that ever did exist, or ever shall be formed, was or can the equality asserted among the members of the human race, be practically enforced or carried out.” He clarified, “There are portions of it, large portions, women, minors, insane, culprits, transient sojourners, that will always probably remain subject to the government of another portion of the community.”

John C. Calhoun tracked this reasoning in 1848 but had in mind bondage and Southern slaves when he announced that “nothing can be more unfounded and false” than the “opinion that all men are created equal.” He pronounced it “a great and dangerous error to suppose that all people are equally entitled to liberty,” which he called “a reward to be earned, not a blessing to be gratuitously lavished on all alike.” That sounds like Babbitt, who labeled the state of nature a “metaphysical assumption.” Recalling Rousseau, Calhoun identified the state of nature—which he dismissed as “purely hypothetical”—as the philosophical origin of equality, adding, “when we say all men are free and equal” in a state of nature, “we announce a mere hypothetical truism; that is, a truism resting on a mere supposition that cannot exist, and of course one of little or no practical value.”

In 1857, Stephen Douglas, refuting the abolitionists, enumerated historical data to, in his words, “show how shallow is the pretense that the Declaration of Independence had reference to, or included, the negro race when it declared that all men created equal.” He continued along these lines with flagrantly racist language that offends twenty-first-century ears.

No wonder we prefer the aspirational reading of Abraham Lincoln, proffered in response to Douglas: The authors of the Declaration, Lincoln intoned, “meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

Lincoln surmised that Jefferson et al. meant the Declaration for “future use,” specifically as “a stumbling block to all those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism.” Lincoln recognized the impossibility of pure equality: “I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity.” The equality that Lincoln praised concerned the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

What would Babbitt’s humanism make of equality? Is equality an insatiable abstraction that incites or inspires (depending on your point of view) endless innovations to social and political measures that can never realize in practice such a lofty ideal? Might equality give way to “centrifugal tendencies,” to borrow phrasing from Babbitt, because it hasn’t an “integrating element”?

The distinction between equality of worth and equality of ability or role seems consequential. But how to institute government or law around equal worth? The problem is practicality. To enforce the concept of equal worth requires an inequality in station or rank: someone with the ability or authority over others to enforce the ideal. When things go wrong, as they inevitably will, alleged violations of the principle of equal worth must be brought before a person or tribunal with superior status and function.

The distinction between the concept of “sameness” and “equality” presents difficulties as well. So long as there are differences between people, there is no pure equality. We don’t want people to be identical, and that’s an impossibility anyway. In one sense we may be “equal in God’s eyes,” but in the Judeo-Christian tradition, among others, even God distinguishes between individuals and groups. How to predicate government on a notion like equality when every operation of law, and every human relationship from parent to child on down, involves inequalities?

The dogma of equality and the doctrine of popular sovereignty have survived Babbitt’s denunciations maybe because democratized standards have placed Babbitt out of the reach of most readers.

Eventually, the route towards equality reaches a point beyond which desired parities require leveling and coercion. Should the ethos be destructive or constructive, should our culture seek to tear down or build? The pursuit of equality leads to its opposite, tyranny. “The type of individualism” emanating from “the doctrine of natural equality,” grumbles Babbitt, “has led to monstrous inequalities and, with the decline of traditional standards, to the rise of a raw plutocracy” (rule by the rich). The irony, for Babbitt, is that attempts to achieve equality yield inequalities just as the “democratic movement” yields, not the rule of the many, but the rule of a few. Both goals become imperialistic.

The Declaration and Popular Sovereignty

Consider, finally, popular sovereignty, expressed in the Declaration as an abstract “people” who supposedly consented to a government that they may later abolish. Babbitt complained that this doctrine germinated with Rousseau and encouraged “a sort of chronic anarchy.” He traced the leveling and destructive cause of the French Jacobins to the spread of popular sovereignty, which set America on the wrong course.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in England as elsewhere in Europe, sovereignty resided with the king. The Glorious Revolution hastened the shift in sovereignty from the monarch to Parliament. The colonials of The First Continental Congress appealed to King George with a seventeenth-century interpretation of English constitutionalism (whereby sovereignty resided in the monarch) rather than with the eighteenth-century doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. George III did not possess the royal power that Congress attributed to him and could not have satisfied the colonists’ pleas for intervention on their behalf.

Sovereignty was in flux. While Sir William Blackstone maintained that Parliament enjoyed absolute sovereignty, James Wilson avowed that “all Power was originally in the People—that all the Powers of Government are derived from them—that all Power, which they have not disposed of, still continues theirs—are maxims of the English Constitution.” That, in short, is the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which contributed to what Babbitt styled “democratic idealism” with its “unbounded faith in the plain people.”

There was English precedent for popular sovereignty, from Magna Carta to the Petition of Rights to the English Bill of Rights. But a Lockean-like conception of sovereignty was hardly the consensus during the American Founding. Babbitt, looking back, didn’t like this conception. He credited its proliferation to Rousseau’s Social Contract. “Practically,” Babbitt says, “the most important precur[s]or of Rousseau in the development of this doctrine [of popular sovereignty] is Locke,” another of Babbitt’s bugbears. “The doctrine of natural rights, as maintained by Locke,” Babbitt contends, “looks forward to the American Revolution, and, as modified by Rousseau, to the French Revolution.”

Jefferson, extending Locke, was not, in Babbitt’s mind, “for increasing the inner control that must, according to Burke, be in strict ratio to the relaxation of outer control.” Babbitt denigrated the youth of his day as “young Jeffersonians” who frittered away their time pursuing a happiness without standards. Babbitt says of them, “When the element of conversation with reference to a standard is eliminated from life, what remains is the irresponsible quest of thrills.” He faulted Jefferson for societal ailments: “Our present attempt to substitute social control for self-control is Jeffersonian.”

Why this animus towards Jefferson? Because Babbitt blamed Jefferson, in part, for the “present drift away from constitutional freedom” following the “progressive crumbling of traditional standards and the rise of a naturalistic philosophy that, in its treatment of specifically human problems, has been either sentimental or utilitarian.”

Babbitt contrasted the United States Constitution (represented by George Washington) and the Declaration (represented by Jefferson): “The Jeffersonian liberal has faith in the goodness of the natural man, and so tends to overlook the need of veto power either in the individual or in the state. The liberals of whom I have taken Washington to be the type are less expansive in their attitude toward the natural man.”

Jefferson was expansive and democratic in the vein of Rousseau, in Babbitt’s dichotomy, whereas Washington exemplified restrained constitutionalism in the vein of Burke. The Washingtonian and Jeffersonian modes were both liberal, in the broadest sense, but the latter, Babbitt posited, was more “fraternal” and “abstract”—like the sentimental idealism of Rousseau.

Interestingly, Babbitt categorized Lincoln with Washington, not Jefferson, even though Lincoln considered Jefferson and the Declaration to be sources of his politics. Lincoln alleged that the Declaration “contemplated the progressive improvement in the condition of men everywhere.” That sounds suspiciously like Baconian naturalism with its “ever-growing confidence in human perfectibility,” to quote Babbitt, who noticed “a strongly marked vein of sentimentalism in Lincoln.” Yet Babbitt mythologized Lincoln as a proponent of judicial review and hailed unionism for reasons too complicated to elucidate here. Suffice it to say that, regarding Lincoln, Babbitt was egregiously wrong.

Popular sovereignty has vast cultural and not just governmental implications. It breeds egalitarianism, which Babbitt pitted against “traditional standards.” In fact, Babbitt adjudged that America “lacks standards” or confused and inverted standards, which, surely, have worsened since. Democracy esteems quantity over quality and venerates the lowest common denominator, resulting in “vulgarity” and “triviality” (Babbitt’s words) and the erosion of rigor. Its inclusivity grants bad ideas the same or similar standing as good ideas, so that its proponents wittingly or unwittingly disincentivize the pursuit of merit and excellence.

Our Declining Standards

The dogma of equality and the doctrine of popular sovereignty have survived Babbitt’s denunciations maybe because democratized standards have placed Babbitt out of the reach of most readers. He’ll never win over masses because he is no voice for popular sentiment. His audience is initiated into higher levels of discourse than even most college graduates can handle. If Babbitt still has admirers, then society has not yet degenerated into egalitarian mediocrity.

Judging by the caliber of our politicians, government officials, journalists, university professors, scientists, and the like, one is justified in concluding that standards have diminished, leaving us with cheap categories like equity and inclusion. Babbitt issues this haunting reminder: “The decline of standards and the disappearance of leaders who embody them is not some egalitarian paradise, but inferior types of leadership.” If democracy and equality are self-defeating, then there is little hope for the United States of America, the leadership of which has become, alas, mediocre. Some form of sentimental imperialism will inevitably befall us.

Babbitt’s articulation of humanism might seem alien and pedantic, the kind of irrelevant, bygone posturing of high-minded academics divorced from the quotidian realities of ordinary people. The categories he employed—Baconianism versus Rousseauism, humanism versus humanitarianism—seem grand and curious. Yet they refer to beliefs and convictions that are very much with us. They remain relevant. And we are mistaken and misguided to ignore them.