The Hat Riots of 1922 show how arbitrary, elite rules can spur civil unrest.

Rekindling the Sparks of the Spirit

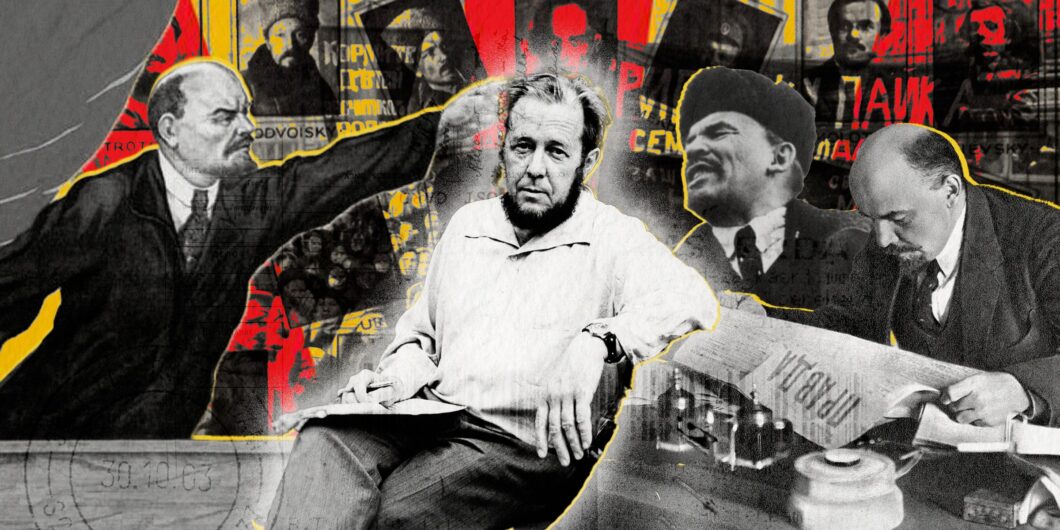

Solzhenitsyn, a living tradition, a living legend, has once more run the blockade of muteness; he has reinvested the deeds of the past with reality, restored names to a multitude of victims and sufferers, and most importantly, he has re-endowed events with their true weight and instructive meaning.

We have discovered it all anew, we hear and see what it was all like: search, arrest, interrogation, prison, deportation, transit camp, prison camp. Hunger, beatings, labor, corpses.

The Gulag Archipelago.

–Lydia Chukovskaya, Moscow, February 4, 1974 (published in samizdat)

In her richly evocative tribute to The Gulag Archipelago, the Russian novelist Lydia Chukovskaya perfectly captured the haunting substance and profound moral significance of one of the greatest books of this, or any other, time. Published in Russian by YMCA Press in Paris on December 28, 1973, and within months appearing in most major languages, this book—an incomparable “experiment in literary investigation” as the author chose to call it—masterfully combined a devastating account of Soviet repression and terror between 1918 and 1956, intermixed with an ample account of Solzhenitsyn’s own experience between 1945 and 1956 in prison, camp, and internal exile, with philosophical reflection of the first order. Throughout, we see the author in search of self-knowledge in a manner that he himself calls Socratic. With his back against the wall, but with endless time to reflect on the truth of the soul and the order of things, this “literary investigation” also provides a profound meditation on “the soul and barbed wire.”

The Gulag Archipelago also has something of the character of what is now called “oral history” since it drew on the eyewitness accounts of 257 people who fell victim to the Communist juggernaut and the gulag camps more specifically. Since 2007, their names have been listed in Russian editions of the book, with an expression by the author of heartfelt indebtedness. Written between 1958 and 1968 (most of it in a secretive “Hiding Place” in Estonia in the winters of 1965 and 1966), its publication was finally forced on Solzhenitsyn when the KGB seized a clandestine copy of the book in September 1973. Without hyperbole, it can be said that its publication changed the world. Eventually selling more than thirty million copies globally, it contributed to the comprehensive delegitimization of support for the Soviet Union, and the Communist ideology that informed it, both in the Soviet Union and in the Western democracies. In its pages, Solzhenitsyn took pointed aim at the ideological justification of tyranny and terror and the chimerical affirmation of a “New Man” who was nothing more than the old Adam brutalized by violence and spiritually worn down by betrayal and mendacity as “forms of existence,” as Solzhenitsyn suggestively called them. This was the truth of full-blown totalitarianism, an all-out assault on bodies and souls, and not the comparatively benign authoritarianism of the Tsars of old, a point returned to repeatedly throughout the three volumes of the work.

“An Upsurge of Strength and Light”

In her 2009 “Foreword” to the Russian abridgment of the work, which will be available in English in the 50th anniversary edition of The Gulag Archipelago (abridged version) to be released by Vintage Classics in London on December 7, 2023, Solzhenitsyn’s widow, Natalia Solzhenitsyn, highlights the fact that the system of prisons and camps that morphed into the gulag archipelago was “merely the heir and the child of the [Bolshevik] Revolution.” She adds: “The accursed Archipelago was not at all produced by some sequence of errors or ‘violations of legality,’ but was the inevitable outcome of the System itself, because without its inhuman cruelty it would not have been able to hold on to power.” Hence its power as an analysis of what has been called “utopia in power.”

But at a deeper level, she continues, this three-volume masterpiece is more than the “source of information about past epochs,” however lamentable they may have been. Citing Solzhenitsyn’s famous insight from the chapter on “The Bluecaps” (repeated in a slightly different form in the later chapter from volume 2 entitled “The Ascent”) that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through every human being,” Natalia Solzhenitsyn suggests that the book is best understood as an “epic poem.” While taking aim at various forms of ideological Manicheanism, the book is ultimately “about the ascent of the human spirit, about its struggle with evil.” It is a book that affirms much more than it negates. At “the end of the work” its readers “feel not only pain and anger, but an upsurge of strength and light.”

The Fingers of the Aurora

The second volume of The Gulag Archipelago begins with a sentence at once elegant and resonant: “Rosy-fingered Eos, so often mentioned in Homer and called Aurora by the Romans, caressed, too, with those fingers the first early morning of the Archipelago.” What a rich evocation of Homer’s much-invoked “rosy-fingered dawn”! It becomes much more than a literary allusion, however, in Solzhenitsyn’s appropriation of the phrase.

In Lenin’s hands, good and evil have been completely and utterly relativized. What is good is whatever serves the cause of revolution, no matter how intrinsically evil or ignoble.

The Aurora was the Russian naval vessel, commandeered by revolutionary sailors, that sailed down the Neva River in Petrograd on October 23, 1917 (according to the old Julian calendar), as a signal for Bolshevik forces to seize major government outposts and to storm the famed Winter Palace. The latter served as the headquarters for the ineffectual Provisional Government of liberals and socialists which had long ceased to govern Russia and perhaps never really did (a claim that is central to Solzhenitsyn’s narrative in his other great epic, The Red Wheel). Solzhenitsyn’s point here, made with literary aplomb, is that totalitarian coercion in the form of the gulag archipelago, and the “Red Terror” more broadly, was coextensive with the forcible imposition of the Communist or Bolshevik regime itself in 1917. The Cheka, the Communist secret police, was founded within weeks of the revolution. It was charged with taking immediate aim at so-called “enemies of the people,” real or imagined. This was “no accident,” as Marxists like to say. Marx and Engels themselves had taught without compunction, in Solzhenitsyn’s apt summation, “that the old bourgeois machinery of compulsion has to be broken up, and a new one created immediately in its place.” Lenin went even further in this vein, demanding that “the most decisive, draconic measures” were needed to “tighten up discipline” among recalcitrant workers who mistakenly had thought that a “worker’s revolution” would bring something other than iron discipline. In the sardonic tone that is one of the defining voices of The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn asked, “And are draconic measures possible—without prison?”

With Lenin’s Decree on the Red Terror published on September 5, 1918, concentration camps to isolate “class enemies” would quickly follow, as well as the deliberate sinking of thousands of “bourgeois hostages” on barges in the Neva and other bodies of water. The latter were drowned simply for belonging to a social class that was arbitrarily and brutally defined as “exploitative.” The murderous logic of ideological Manicheanism thus revealed itself from the earliest days of Bolshevik rule. Jacobinism was reborn in a much more virulent form.

Lenin and “Insect-Purging”

In an earlier chapter of The Gulag Archipelago, near the beginning of volume 1, bitingly entitled “The History of Our Sewage Disposal System,” Solzhenitsyn made clear the Leninist, not Stalinist, origins of the Soviet system of tyranny and terror. Near the beginning of the chapter, he discusses a remarkably revealing essay by V. I. Lenin entitled “How to Organize the Competition,” composed on January 7 and 10, 1918. The founder of the Soviet regime wrote this essay, not published until after his death, to clarify his thoughts on the need for the swift purgation of “enemies of the people,” broadly and loosely defined.

In prose that is endlessly vituperative, fanatical, and inhuman, Lenin compares independent intellectuals, merchants and bourgeois, religious believers, and workers who allegedly “malinger” at their posts, to “atrophied limbs” and “cancerous” growths that must be excised for the sake of the revolutionary transformation of human beings and society. Non-Bolshevik intellectuals are now characterized as “saboteurs.” All around him, Lenin saw “harmful insects” who must be “purged” from the Russian lands. Neither Hitler nor Stalin surpassed Lenin in hate-filled invective, even if they rivaled him. As Solzhenitsyn points out, in the 1918 essay Lenin calls for endless “experimentation” in “insect-purging.” Some “insects,” he remarked, are to be imprisoned, others to be shot, some to be “re-educated,” others to be sent to “clean latrines,” while others were to be sentenced to “forced labor of the hardest kind.”

Lenin clearly relishes revolutionary terror and says or does nothing to minimize it, or even to define it as an unfortunate necessity. He expresses unrelieved contempt for the moral law and the imperatives of the human conscience. In his hands, good and evil have been completely and utterly relativized. What is good is whatever serves the cause of revolution, no matter how intrinsically evil or ignoble. No cost is too high to pay for the fanciful project of completely remaking human beings and society. In other words, the ideological “Second Reality” dreamed of by Marxism-Leninism justifies the unjustifiable, as its adherents lose living contact with the real world and its moral contours, its real possibilities and limits, its constitutive grandeur and misery. Lenin is the first of the twentieth century’s ideological monsters, a theorist/practitioner who vehemently warred with both human nature and moral conscience. In this, he followed the lead of the unconscionable Marx. Without Marx, there is no Lenin, and without Lenin, there is no Stalin or Mao.

Collectivization Forgotten

As Solzhenitsyn amply demonstrates in the same chapter, the “abuses of the cult,” the Stalin cult of personality, would come much later and with it the phenomenon of the Revolution devouring its own. The terror would eventually turn against members of a Communist party who had long cheered on and justified, and participated in, mass repression against the “flower of the nation,” good and honest people who dared not corrupt their souls by becoming complicit in the violence and lies that from the very beginning defined ideological despotism in its Bolshevik form. As one might expect, the religious-minded—clergy, laymen, members of religious study groups, Tolstoyans, monks, Orthodox and non-Orthodox believers alike—suffered disproportionately from an aggressively atheistic regime.

In one of the final chapters of The Gulag Archipelago, “The Peasant Plague,” Solzhenitsyn lamented the fact that there were “no books” about the millions of peasants—who perished as a result of the war against the independent peasantry.

In 1929 and 1930, and the years that followed, millions of peasants were swallowed up in a massive wave of repression as a result of the forced collectivization of agriculture, a measure that no rational state, guided by ordinary political considerations, would have undertaken. The war against the so-called kulaks, industrious and independent peasants who sometimes owned no more than a small plot and a few extra cows, was, in Solzhenitsyn’s view, the most monstrous crime of the Soviet regime. Whole peasant families, hundreds of thousands of them, were sent into the “tundra and taiga” of Siberia, and many directly into the ever-expanding “Gulag country.” Solzhenitsyn states unequivocally that “there was nothing to be compared with it in all Russian history.” It took aim at “all strong peasants in general”—”all peasants strong in management, strong in work, or even strong merely in convictions. The term kulak was used to smash the strength of the peasantry.”

In one of the final chapters of The Gulag Archipelago as a whole, “The Peasant Plague,” Solzhenitsyn lamented the fact that there were “no books” about the millions of peasants—who perished as a result of the war against the independent peasantry. These included millions of Russians and Kazakhs, as well as collectivization’s better-known Ukrainian victims. They were the “backbone” of the country but, as simple, unlettered people, they did not write books. It was “a second Civil War—this time against the peasants.” The “nub of the plan” was that “the peasant’s seed must perish with the adults.” Solzhenitsyn bitingly remarks that “since Herod was no more, only the Vanguard Doctrine,” Marxism-Leninism with its deluded claims to stand for the inevitable “progress” of the human race, “has shown us how to destroy utterly—down to the very babes.”

The Gulag Archipelago in Russia Today

At this point, I may be permitted an observation that bears on the contemporary scene. Today, the governing authorities in Russia are not remotely pro-Bolshevik, even if they want to control the message about Communist criminality, and have therefore, lamentably, taken aim at independent groups such as “Memorial.” But they adamantly refuse to tolerate any comparison of Communist ideology, or the Soviet regime, with what in their view is the ultimate evil, National Socialism.

Why? The legitimacy of Putin’s Russia increasingly rests on the cult of the “Great Patriotic War.” The sacrifices of the Soviet people against the Nazi invader certainly deserve to be honored and honored justly. But this new cult contains important elements of the old ideological lie. It is presented absent an honest rendering of the nefarious Hitler-Stalin Pact, and of the responsibility (in part) of the Soviet regime for the death of so many Soviet soldiers and citizens during the war through the reckless destruction of the Red Army’s officer corps during the Great Terror of 1934–38, the intensification of repression in the gulag even as the country was at war, and the inexcusable sending of wave after wave of ordinary Ivans to their slaughter with no military advantage or purpose in mind. To this, one could add the cruel and thoroughly unjust sending of millions of Soviet prisoners of war in Germany to the gulag after they returned home after the war. This is a whitewashing of history that verges on the ideological, and against which Solzhenitsyn regularly warned. Many in Russia today, however, Communists to be sure, but also including members of Putin’s “United Russia” party, attack Solzhenitsyn for refusing to excuse collectivization and mass terror, as “necessary,” if “unfortunate,” requirements to prepare the country for the coming war with the Hitlerite enemy. In January 2023, Dmitry Vyatkin, an influential Russian MP from United Russia, demanded the exclusion of The Gulag Archipelago from the Russian school curriculum. He denounced the book as “garbage” written to “cover [Solzhenitsyn’s] own motherland in mud.” Solzhenitsyn, it was crudely said, wrote the book for no other reason than to “get an award” for attacking his country. Happily, many members of the ruling party came to Solzhenitsyn’s defense and President Putin still favors its inclusion in the school curriculum.

In contrast to this emerging Russian consensus, Solzhenitsyn refused to whitewash the criminal responsibility and monstrous evil that was Leninist-Stalinist totalitarianism. Moreover, he saw that regime as anti-Russian to its core. To identify it with “eternal Russia” was a grotesque error, especially since the Russian people were the first to suffer from it. As for its moral quality, that regime was as bad, and perhaps at times even worse, than the equally murderous Hitlerite one. In “The Peasant Plague” the Russian writer stated with the sardonic irony that was his that “Hitler was a mere disciple [of Lenin and Stalin], but he had all the luck, his murder camps have made him famous, whereas no one has any interest in ours at all.”

“A human being has a point of view!”

In an early chapter on “Interrogation,” Solzhenitsyn points out that orthodox Communists, and those whose moral vision had been hopelessly distorted by the progressivist delusion that Communism represented the inexorable wave of History, had no real ground, no resources within their souls, to stand up to their interrogators. They had already been “pitiless in arresting others” and in slavishly following the party line. The ideological lie was deeply implanted and engraved in their souls.

These murderers, and apologists for murder along ideological lines, did not deserve their “martyr’s halos.” Solzhenitsyn forthrightly concludes that in studying “in detail the whole history of the arrests and trials of 1936 to 1938,” the years when the Revolution began to devour its own children, “the principal revulsion you feel is not against Stalin and his accomplices,” as terrible as they were, “but against the humiliatingly repulsive defendants, nausea at their spiritual baseness after their former pride and implacability.” A seemingly harsh judgment, but one that rings true.

Communism, and modern theory and practice more broadly, has increasing turned human beings away from the things of the spirit, from the wellsprings of conscience, from the rich and enduring intimations of natural justice and God’s grace.

Solzhenitsyn saved his unreserved respect and admiration for those with a principled “point of view,” those who remained faithful to the human spirit and conscience and rejected both mendacious ideology and a base concern for self-preservation. He highlights the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyayev’s refusal to kowtow to the Cheka when he was personally interrogated by its fanatical leader, Feliks Dzerzhinsky. Berdyayev refused to “humiliate himself” before his interrogators. Instead, he “set forth firmly those religious and moral principles which had led him to refuse to accept the political authority established” by the Bolsheviks in Russia. With Berdyayev, intellectual and moral integrity stood steadfast against the ideological lie. Rather than being arrested, imprisoned, or killed, Berdyayev was forcibly exiled from the Soviet Union in the fall of 1922 on the so-called philosopher steamer, one of 228 independent-minded thinkers, scholars, and students deported on the personal order of Lenin.

Solzhenitsyn also recalls a peasant woman, deeply imbued with Christian faith, who as part of an underground network had helped an Orthodox Metropolitan flee the Soviet Union during a period of the most intense religious persecution. She told her interrogators that there is nothing they could do, “even if you cut me into pieces,” that would make her betray the “underground railroad of believers.” They [her interrogators], she rightly pointed out, lived by fear, and knew that by killing her they would “lose contact with the underground railroad.” At once calmly and with utmost determination, she declared, “I am not afraid of anything. I would be glad to be judged by God right this minute.” She stood firm as a rock, faithful to truth and the just judgment of God.

With these two admirable examples in mind, one a philosopher, the other a simple peasant woman, Solzhenitsyn laconically but forcefully proclaims, “A human being has a point of view!” This is what cynics, pseudo-sophisticates, materialists, and ideologists, cannot see. They are blind to the reality of the human soul and the moral, spiritual, and intellectual sources that inform and elevate human freedom. Communism, and modern theory and practice more broadly, has increasingly turned human beings away from the things of the spirit, from the wellsprings of conscience, from the rich and enduring intimations of natural justice and God’s grace. What a massive price modern man has paid for this moral and intellectual emancipation from the most fundamental realities!

Poetry in the Camps: The Recovery of the Human Countenance

But even in the camps, the things of the spirit refuse to perish, and in multiple ways point to the primacy of the Good. Every reader of Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece would be well-advised to spend time with two chapters from the third volume of that work, “Poetry Under a Tombstone, Truth Under a Stone” and “The Forty Days of Kengir” (where 8,000 prisoners, political prisoners and criminals alike, courageously rose up in the spring of 1954 against their oppressors and established “self-government”—the term is Solzhenitsyn’s—if only for forty spiritually ennobling days). These memorable chapters powerfully display the refusal of the human soul to surrender to hate-filled violence and to the ideological lie that denies that human beings have souls in the first place. In one of the first and still most discerning commentaries on The Gulag Archipelago, written in 1974, the late Russianist John B. Dunlop rightly called The Gulag Archipelago a hope-filled “personalistic feast.” The two aforementioned chapters richly illustrate this point.

In “Poetry under a Tombstone, Truth Under a Stone” we meet the humane religious poet Anatoly Vasilyevich Silin, who not only became a believer in the camps, but something of a philosopher and theologian as well. The poems that he memorized in the camps (much like Solzhenitsyn himself), “composed from end to end without writing a word down … went round and round in his head.” He saw beauty in nature and believed that God’s grace could, in principle, redeem even the most perverted will. In a striking passage, Solzhenitsyn notes that “the atheist’s refusal to believe that spirit could beget matter only made Silin smile.”

Solzhenitsyn concludes this remarkable chapter by noting how the camp regime attempted to “depersonalize” everyone, giving every zek “identical haircuts, identical fuzz on their cheeks, identical caps, identical padded jackets” and impersonal numbers in place of names. Yet the human face is not so easily abolished, even if the “image of the soul” that continues to shine through is “distorted by wind and sun and dirt and heavy toil.” The task of the philosophical poet, Silin, but most especially Solzhenitsyn himself, is nothing less than to discern “the light of the soul beneath this depersonalized and distorted exterior.” In the battle between an art inspired by true philosophy and religion, and in tune with the human experience of good and evil at work in the degraded conditions of the forced labor camps, ideology must inevitably lose: “The sparks of the spirit cannot be kept from spreading, breaking through to each other. Like recognizes and is gathered to like in a manner none can explain.” But the philosophical poet can describe these “sparks of the spirit” that refuse to be crushed by men and regimes who have forgotten what it means to be human.

Can It Happen Again?

Is the gulag archipelago a thing of the past, a particularly vivid and cruel manifestation of “man’s inhumanity to man,” as the cliché goes, but now resting comfortably in the dustbin of history? Solzhenitsyn feared that it was not. As long as the ideological lie persists, that is, as long as “Evil” is localized in suspect groups who are endlessly “scapegoated,” as René Girard would have it, then totalitarianism is free to manifest itself ever more inventively in theory and practice. As Jordan B. Peterson has written in his lucid foreword to the 2018 edition of the authorized abridgment of The Gulag Archipelago, today in the West “the doctrine of group identity” renews the ideological lie by placing whole swaths of individuals in suspect groups as the new “class enemy,” deemed “oppressors” for whom there can be no mercy. But when everyone, or almost everyone is “guilty,” Peterson adds, “all that serves justice is the punishment of everyone” in a logic that is coextensive with the gulag archipelago itself. Solzhenitsyn has warned us and has shown us ad oculos where this deranged “utopian vision” leads. Because of Solzhenitsyn’s example and lessons, his inspired “outrage, courage, and unquenchable thirst for justice and truth,” we have no excuse if we choose to continue to go down the deadly road to catastrophe.

What might just save us as we ascend the precipice? In the most essential chapter of the book, “The Bluecaps,” Solzhenitsyn reflects on what saved him as a young man from becoming an NKVD officer when he was still a committed young Communist. Despite his ideological commitments, the thought of becoming a secret police agent made Solzhenitsyn “feel sick,” and filled him with “a sense of revulsion.” In his own words, he was “ransomed by the small change in copper that was left from the golden coins our great-grandfathers had expended, at a time when morality was not considered relative and when the distinction between good and evil was very simply perceived by the heart.” What a beautiful image and insight! If we are to stave off catastrophe, we must do what many deem impossible: we must become naïve again, returning to the world of common sense and moral conscience where good and evil first come to sight. In addition to our own active efforts, let us hope and pray that a few of those copper coins of old are still available and that the moral scruples that are part and parcel of our souls can again gain a hearing in a world increasingly dominated by loud voices at the service of ideological distortions. No book can better rekindle those scruples, those essential elements of our humanity, than The Gulag Archipelago.