In a time where the average age of Supreme Court Justices keeps rising, lifetime appointments may not make sense anymore.

Our Universal Literary Inheritance

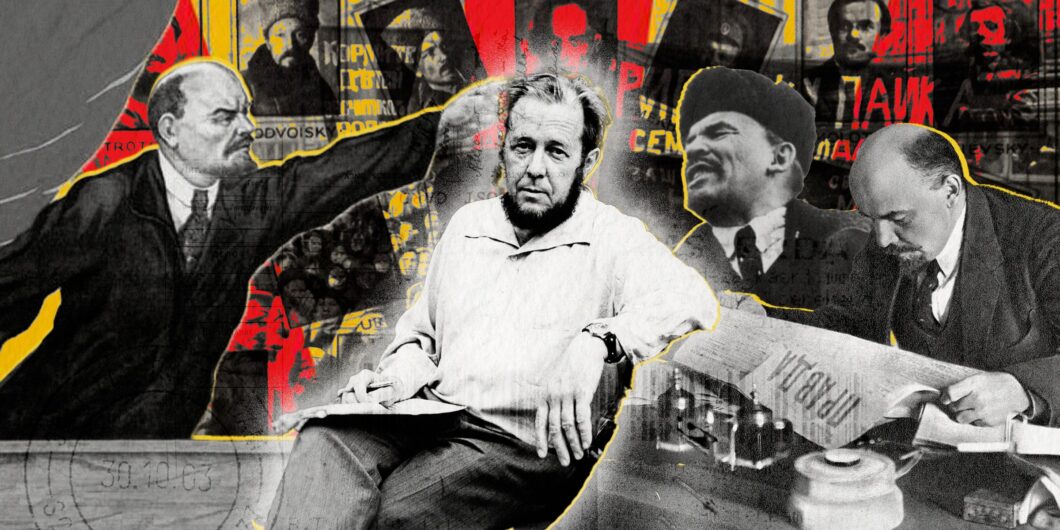

It was 2011, and the sun set in Moscow around 4 p.m. So we approached his vacant apartment in the dark. His wife Natalia informed me that they were converting it into a museum. We toured the small space in silence, her son Stepan and my mentor Edward E. Ericson, Jr. accompanying us. I snapped pictures like a tourist and felt an emptiness in my gut as I did so. The space was suffused with a suffering I could not personally identify. But because I had read The Gulag Archipelago, I could imagine the terror of that evening February 12, 1974, when Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was arrested for the second time.

Solzhenitsyn writes of his 1945 arrest in the opening chapter. “Arrest!” he exclaims, “Need it be said that it is a breaking point in your life, a bolt of lightning which has scored a direct hit on you?” Neither time that Solzhenitsyn was arrested was he a criminal, in the way that Americans often conceive of that word, but the Soviets came for everyone who told the truth, everyone who refused to kowtow to the lies of the Communist empire. As Gary Saul Morson has repeatedly pointed out, in Soviet Russia, “truth is whatever serves the Party’s interests,” a fallacy that Solzhenitsyn rejected. “Live not by lies,” was his famous battle cry, released the day he was arrested.

The 1974 arrest was for writing his nearly 500,000-word literary experiment The Gulag Archipelago, which had been smuggled west and published covertly. It received the Nobel Prize for literature, and the award probably saved Solzhenitsyn’s life. He was too well-known to execute. About the book, Dan Mahoney notes, “Without hyperbole, it can be said that its publication changed the world.” Following the publication of these three volumes, no one could say—without lying to themselves—that communism in Russia was the peaceful way toward a future utopia.

We see the continued violence caused by the mendacity of the Russian government in their invasion of Ukraine. If you live in Russia today, you will hear false narratives about the war against the Ukrainian people, and those offering up counter-evidence, such as Masha Gessen, are silenced. Solzhenitsyn’s mother was Ukrainian, and Solzhenitsyn was torn regarding the state of the independent country. In The Gulag Archipelago, he writes, “It pains me to write this as Ukraine and Russia are merged in my blood, in my heart, and in my thoughts. But extensive experience of friendly contacts with Ukrainians in the camps has shown me how much of a painful grudge they hold. Our generation will not escape from paying for the mistakes of our fathers.” As with many of his prophecies, Solzhenitsyn was correct.

Solzhenitsyn condemned lies that seem decades and countries removed from us, yet ideology is as contagious in America as it is in Russia.

It would be a mistake to see Solzhenitsyn in line with the Russia of 2023. Vladimir Putin may still favor The Gulag Archipelago as required reading for Russian children, as Mahoney mentions, but that does not place the Soviet dissident in his camp. Remember that Nikita Khrushchev published One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich without realizing how much it indicted his own dictatorship; he only saw it as a denouncement of Stalin. Similarly, when writers such as Tomiwa Owolade castigate Solzhenitsyn as paving the way for Putin’s war, he errs in his reading of history. Owolade is more on the mark when he writes, “Solzhenitsyn is the dissident writer-intellectual incarnate. He makes Orwell, Camus, and Koestler look like pygmies.” Solzhenitsyn never would have approved of an invasion of his mother’s country, nor any tyrannical attempts to force others to comply with one’s will. This was a man whose most-used word was “freedom.” In The Gulag Archipelago, reflecting as a zek (prisoner) on his former liberated state, he laments, “We didn’t love freedom enough.”

So how are we to read The Gulag Archipelago, as Americans in the twenty-first century reading a Russian author while witnessing a brutal war of aggression committed by Russians?

Solzhenitsyn wrote these stories at the risk of his own life, and he dedicated the book “to all those who did not live to tell it.” There’s an additional caution in his dedication, “And may they please forgive me for not having seen it all nor remembered it all, for not having divined all of it.” Such a dedication may sound odd: how could Solzhenitsyn be guilty of not seeing, not remembering, and especially not knowing ahead of time what would happen? His dedication offers us a key to reading this book rightly. If we are to avoid a similar guilt, we must read this book. “Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everyone on earth. Yet, I have not given up all hope that human beings and nations may be able, in spite of all, to learn from the experience of other people without having to go through it personally.” Solzhenitsyn hopes we may learn from others’ history rather than repeat it ourselves. Just as Elie Wiesel’s Night demands that others, in imitation of the author, “Never forget,” so does The Gulag Archipelago implore readers to write these stories on their hearts.

Mahoney cites the most famous line from The Gulag Archipelago that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through every human being.” Not between states, nor classes, nor political parties, Solzhenitsyn writes, “but right through every human heart … even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains … an uprooted small corner of evil.” In other words, Darth Vader may kill the emperor in the end and save his son, but so too might Frodo turn on Mount Doom and clutch the ring for himself. The fantasy stories sometimes tell the truth better than history. Unless the history is retold by Solzhenitsyn, in which case, the rebels at Kengir, the portraits of Stalin, or the poets behind barbed wire have much to teach us. We read their stories not only as a caution for ourselves but also as a way to remember others’ sufferings and heroics.

Solzhenitsyn condemned lies that seem decades and countries removed from us, yet ideology is as contagious in America as it is in Russia. We cannot be so credulous as to think the horrors of the gulag would never happen here. Nor can we allow Solzhenitsyn to be censored because he is Russian or to only be exalted by conservative voices; he does not align with American politics and does not belong to the Hall of Fame for one party. He is our universal literary inheritance, alongside Dostoevsky, Akhmatova, and Berdyaev. Mahoney highlights that Solzhenitsyn wrote with “his back against the wall.” That is how we should see Solzhenitsyn: the poet who sacrificed bread to use as rosary beads for memorizing verse, the father arrested before his wife and three sons because he would not live by lies, the man willing to keep his back against the wall if it meant retaining his humanity. It is that man who gave us The Gulag Archipelago, and we show our gratitude by continuing to celebrate the book fifty years later.