“Never Forget”

“Lenin is the first of the twentieth century’s ideological monsters.”

—Daniel J. Mahoney

Before the Jews entered the land of Israel, their God laid down the commandments that would mark them as his own. There was one warning that could fairly be said to sum up all the rest, an urgent word from Moses as he approached the threshold of death. The people would carry it with them as they went on without him across the Jordan: Z’kor. Al tish’kach. “Remember. Do not forget.”

Never forget the 40 years of thirst and confusion when you stumbled toward Jerusalem, the long desert days of bitterness when you doubted God. After you cross that river and you eat the good things there, as the promised land starts to pour forth vines and music and children, remember how your fathers were slaves and who rescued them from Egypt. Remember. Do not forget.

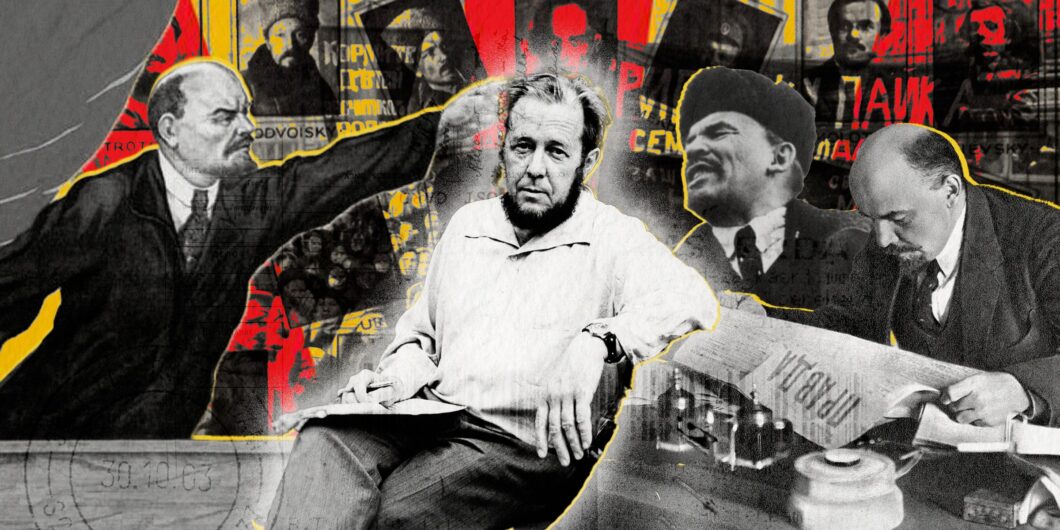

They did forget, of course. We always do. And forgetting brought exile—more wandering, more pain. It always does. Over 30 centuries later, when his own nation had knelt to its own false gods, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn watched it all happen again. For though Soviet Russia was a world away from Biblical Israel, and though the ruthless Party of Stalin sculpted its idols in steel instead of stone, Solzhenitsyn could not improve upon the ancient diagnosis. “Men have forgotten God,” he said in his 1983 Templeton Lecture, quoting the old men he knew as a boy. “That’s why all this has happened.”

In his magisterial tribute to Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, Daniel J. Mahoney expands on a remarkable observation by the great man’s widow, Natalia. The thousands of pages that Solzhenitsyn piled up frantically in secret have been categorized as prison memoir, as polemic, as political philosophy, and as countless other things besides—but The Gulag Archipelago is more than all that, writes Natalia. It is an epic poem. And what is an epic poem if not a memorial? The Iliad’s Greek general Agamemnon, trying to force his war with Troy to its conclusion, demands a tribute from his enemies “which will persist even among men yet to come.” The grueling sorrows of war, the glory of its heroes: Homer sang so that they would be remembered.

Solzhenitsyn wrote so that the victims of a godless dictatorship would never be forgotten. He dedicates his whole account “to all those who did not live / to tell it. / And may they please forgive me / for not having seen it all / nor remembered it all[.]” The three volumes that follow are teeming with the voices of the uncountable dead. Indignation at their slaughter gives Solzhenitsyn’s prose its biting clarity; amazement at the dignity of the best among them gives his words their nobility and grace.

From his fellow survivors, he learned more stories of torture and barbarism than his typewriter could keep up with. From his own imprisonment, after a few unguarded criticisms of Stalin sent him headlong into the Gulag’s twisted system, he learned how remorselessly dedicated the Soviet machine was to oppression and death. But Solzhenitsyn also learned, and this is what makes the Archipelago a masterwork, that there is an unseen axis along which the prisoner can tower high above his captors. However broken your body becomes, “your soul, which formerly was dry, now ripens from suffering,” he wrote.

That’s if you haven’t forgotten God. You stood a chance of surviving the camps with your humanity intact only if you had the one thing your tormentors did not: a commitment to something beyond raw power. Something pure that you could cling to, something from a realm untouched by the raging fiends of this world. That realm is what the twentieth century, with its obsession over machinery and the brute laws of physical nature, had forgotten how to see.

Two Powers, One Spirit

Can we remember? After the other great atrocity of the 1900s, the West adopted a new motto: “never forget.” That’s what we said when we discovered the charred and emaciated bodies of Chelmno and Treblinka, when the hellish carnage of Hitler’s war machine appeared in full view. In 1971, Rabbi Meir Kahane echoed a phrase from another epic poem, Yitzhak Lamdan’s Masada: “never again.” Now, on Holocaust Remembrance Day, US embassies repeat the incantations: “Never Forget. Never Again.” Like Job, we wish the memory of suffering and the insights gained from it could be emblazoned forever on our hearts. “Oh that my words were written in a book—that they were chiseled in stone!”

But the human heart is made of flesh, not stone. We have remembered in a superficial sense: the stories of the dead and the records of their names are there still for anyone who cares to look. But the weeks since October 7th have made it all too dreadfully clear that in a deeper sense, we are forgetting. After Hamas massacred almost a thousand Jewish civilians in modern-day Israel, throngs of gibbering supporters took to the streets of Europe to chant things like “gas the Jews.” Professors at American universities hailed the slaughter as “exhilarating” and “extraordinary.” It’s been less than a hundred years since the Holocaust. How can we possibly have forgotten?

Fifty years on from the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, a new vanguard has slipped a different uniform onto the old nihilism, dressing up blood guilt as “equity” and genocide as “decolonization.”

It may be that for all our memorials and all our slogans, there is a deeper truth about the bloodletting of the 1900s that we do not want to remember. It’s the truth Solzhenitsyn dragged out of the depths of his prison cell: the truth that though Hitler was unspeakably evil, he was not uniquely evil. At the opening of volume 2, Solzhenitsyn insists it was the Bolsheviks who invented the grisly theory and practice of the concentration camp in 1918. He quotes instructions passed among Vladimir Lenin and his henchmen to “carry out merciless mass terror” and “secure the Soviet Republic against its class enemies by isolating them in concentration camps.” With characteristically mordant irony, Solzhenitsyn writes: “So that is where this term—concentration camps—was discovered and immediately seized upon and confirmed … and it was to have a big international future!”

Observations like this make it impossible to limit the awful corruption of the age to one madman or one national psychosis. The disease went deeper and spread wider than that. Hitler represented not some fleeting aberration but a shadow that is always lurking in the heart of man, a feral rage that thrashes against the chains of God and the moral law. The materialist philosophies of the industrial age tore those chains away, right at the moment when human hands were laying hold on unprecedented technological power. Without God to restrain our use of that power, we were bound to wield it in service of grim demons and their dark designs. “As for us, we were never concerned with the Kantian-priestly and vegetarian-Quaker prattle about the ‘sanctity of human life,’” seethed the Marxist firebrand Leon Trotsky in 1920. There is the face of Soviet cruelty laid bare. It is the same face that lurked behind the Nazi mask as well.

Changing Clothes

Small wonder that, as Mahoney writes, “neither Hitler nor Stalin surpassed Lenin” in bloodlust. As a gory matter of sheer numbers, the millions dead in Hitler’s Holocaust are matched almost soul for soul by the millions dead in Stalin’s man-made famine. Under the surface differences in their ideological programs, and despite the circumstances of war that would pit Russia against Germany, the driving spirit of totalitarianism remained the same in both nations. It was the spirit of mankind’s enemy, the hateful and mindless savagery of those who have forgotten God. At the “House of Terror” museum in Hungary, where Nazis and Soviets ruled by turns, there is an exhibit called “changing clothes.” It documents the ease with which craven power brokers shed one regime and slipped into another: “They simply exchanged racist theory for the theory of Marxist class struggle; it was a simple matter of changing uniforms.”

In Dominion, his history of how Christianity remade the world, Tom Holland writes that Hitler is now remembered as a kind of secular Satan, a preternaturally deranged freak beyond all comparison. “Communist dictators may have been no less murderous than fascist ones,” Holland writes, but the Nazis “retain their starring role” in modern demonology. Perhaps we have set Hitler apart this way because we can hardly bear to contemplate what it might mean that the soaring rhetoric of Soviet idealism ended in the exact same devastated wasteland as the triumphalist ravings of Nazi anti-Semitism.

As late as 1932, Walter Duranty could win a Pulitzer Prize for writing in to the New York Times from Stalin’s Russia to praise the mild and sensible Soviet regime—despite readily available testimony to the contrary. That’s how desperate we were to look away. Because if evil cannot be safely restricted to one nation or one appalling moment in history, then the sin that raised its disfigured face over Europe lives in us, too. That is what Solzhenitsyn reminded us of, what we cannot bear to remember: “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

Fifty years on from the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, a new vanguard has slipped a different uniform onto the old nihilism, dressing up blood guilt as “equity” and genocide as “decolonization.” These are the people who are leading the manic effort to forget what Solzhenitsyn had to teach. This year, school librarians in Ontario stripped their shelves of books written before 2008 as part of an “equitable curation cycle,” to make room for titles that are more “inclusive and culturally responsive.” They might have recalled that revolutions which begin with a year zero tend to end disreputably. But a lot of the best books about Pol Pot and Robespierre were written before 2008, and learning from the Red Terror would require remembering what it was.

Being children of darkness, the new revolutionaries shun the light of memory. They deface old statues and melt them down into scrap metal. They constantly revise their explanations of events without acknowledging it. They crave the power to criminalize speech “for the common good.” They do all this for the same reason that so many people are now rushing shamefully to defend the cold-blooded execution of still more Jews: they have already forgotten. They wanted to.

In his Templeton Lecture, Solzhenitsyn paused to chastise the celebrity pastor Billy Graham for minimizing religious persecution in the USSR. “Before the multitude of those who have perished and who are oppressed today,” said Solzhenitsyn “may God be his judge.” Solzhenitsyn had the necessity of God graven into his memory by suffering, like those wandering Israelites who made their painful way through the desert to the promised land. But like their wayward descendants, we Americans are so besotted with our material comforts that we can barely look upon sorrow, can barely bring ourselves to remember the wages of sin. Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece endures to remind us—and may God have mercy if we succeed in our efforts to forget.