Requiem and Renewal After 9/11

Rebirth has its rhythms the same as decline. After great tragedy, both are possible; neither is inevitable. Perhaps they are even simultaneous, the one cloaking the germinating seed of the other.

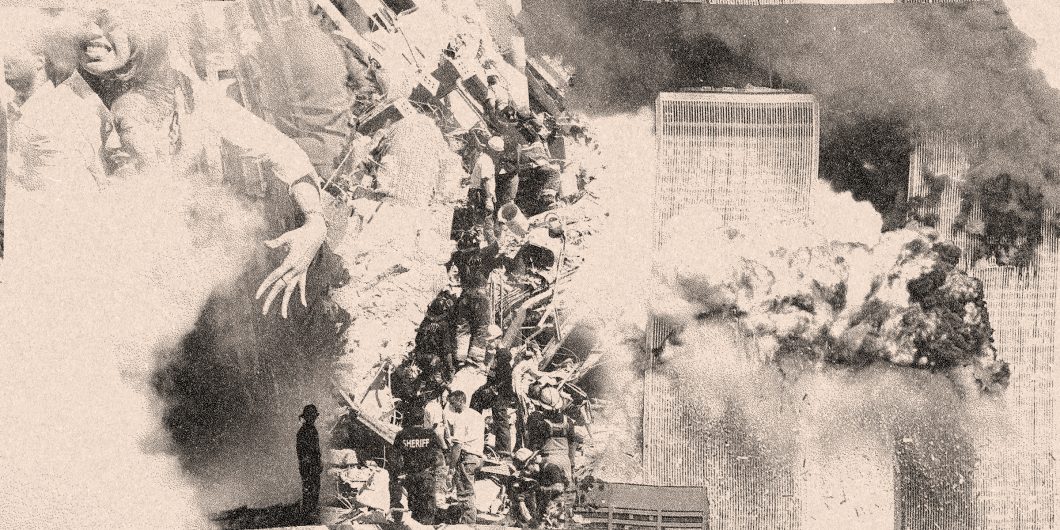

Few would have predicted as morning dawned on Monday, September 10, 2001, that it would be impossible to buy an American flag by the end of that week, because more than four-fifths of Americans would be flying one from their homes, cars, and trucks. Fewer still would have predicted that by week’s end, Americans would be displaying a unity of will and purpose in an avalanche of civic-mindedness. On September 10, the world was too much with us, William Wordsworth might have intoned, “getting and spending, we [were] lay[ing] waste our powers.” Economics and a globalizing commercialism seemed to be the only order of the day, with the harsher side of politics a kind of antiquated afterthought. But on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, as some were being born, and others were starting off their school years or embarking on the first jobs of their careers, nineteen terrorists hijacked four American airplanes, using them as missiles to kill Americans on American soil. And thousands died.

Kyrie Eleison

Afterward, some became teachers and some became soldiers.

Thousands gave of their heart’s blood at Red Cross stations, desperate how else to help. Hundreds of firefighters and police gave their life, rushing to rescue their injured neighbors at Ground Zero. In New York’s Harbor, over six hundred mariners gave their naval assistance to half a million strangers fleeing the sudden destruction of Lower Manhattan. In Canada, thousands of individuals besieged dozens of airports, eager to assist the nearly 60,000 travellers stranded outside the United States.

The ruins of that day’s events smoldered for a long time. The globalized networks of trade, business, labor, finance, and media already in place at the turn of the millennium meant that 9/11 inevitably would have a global impact with repercussions throughout the succeeding years. It also meant that these repercussions would be felt at the level of nations and national governments, as well as at the level of civil society and the individual. War after all, as Heraclitus reminds us, is the universal fire. It enlivens as much as destroys what comes in contact with it. It is a fuelling force.

Afterward, in America as abroad, millions of individuals over the next two decades would give of their treasure—their time, talents, and money—through their donations and creativity; through increased political awareness; by founding new businesses and nonprofits; as well as through paying taxes; to fund an array of national and civil responses to the devastation suffered on that day of infamy, 9/11.

Dies Irae

The four airplanes had torn through the steel of the Twin Towers, the concrete of the Pentagon, and the earth of the Pennsylvanian countryside and instantaneously into the American psyche. Despite its post-Cold War economic, military, and cultural might, America was not untouchable. Far from being universally admired, America was loathed by peoples in countries most Americans could not place on a map, who were unapologetically pursuing political goals antithetical to America’s peace, guided by a concrete desire to harm.

Commentators on both sides of the Atlantic immediately remarked on America’s loss of innocence that September day. What took longer to materialize was a new national intolerance to risk. The federal government quickly created the Department of Homeland Security and the Transportation Security Administration; instituted a color-coded threat level warning system; and passed surveillance legislation through the Patriot Act, which all together completely altered how Americans interacted with their government, travelled, enjoyed their sports and public entertainments, did business, and thought about personal data and privacy—and all before social media took hold.

The heightened focus on security and security measures and the downplaying of the always-existent tensions between these and individual liberties metastasized over the years in favor of the former, all while individuals were blithely removing traditional barriers to their private lives via social media. In April 2013, authorities demanded Bostonians forego their daily lives and remain at home while police conducted a manhunt for Boston Marathon bombers Tamerlan Tsarnaev and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, even searching door-to-door through the streets of Watertown sans warrants and heavily armed; in March 2020, authorities demanded all Americans to forgo their daily lives and remain at home, in order to “flatten the curve” of the COVID-19 virus. And in 2021, authorities are demanding vaccination passports for those wanting to engage in the simple activities of living.

Most all have readily complied—the Nuremberg Code, HIPPA, usual Conservative Big Government skepticism, the “right to privacy” and “my body my choice,” notwithstanding.

Fitting then, for the New York Metropolitan Opera to host their first in-person performance (for the vaccinated) since the COVID lockdowns commenced, on September 11, 2021, the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. Verdi’s dramatic Requiem will be their song.

We know what we mourn. But do we remember what we can honor?

Confutatis Maledictis

Were we at war? Osama bin Laden had declared in 1996 that al-Qaida, anyway, was at war with America. Al-Qaida’s warfare of choice manifested as intermittent hostilities publicized through spectacular targeting: the 1998 bombing of the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam; the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole; numerous other half-baked or thwarted attempts such as the Bojinka plot. Only after these came 9/11.

That war is a state of being as much as a political activity or a set of formulized pronouncements is a classic tenet of political theory, reaching at least to the Enlightenment era if not to Homer. But historian William Anthony Hay seems to divorce war from politics: In his Law & Liberty essay on the twenty-year aftermath of 9/11, he writes of an American overreaction—war—to the 9/11 attacks, “that did more harm than the attacks themselves,” because of the attention it diverted away from other domestic and global issues, as well as because of some resulting international criticism levied at America. But is not demarking one’s friends, from one’s enemies, from oneself, the most elementary political task of all, in order to fulfill this principal political duty—to preserve the way of life of one’s particular political community, the regime, by defending it from adverse pressures and attacks both from within and without? To put it in Shakespearean terms: “To thine own self be true.”

In America, we’ve made this duty explicit. Presidents, elected and appointed government officials, and every member of the US Armed Forces must swear an oath to defend and protect the Constitution and the United States of America against attack. The basic principle is acknowledged even among those international actors Hay mentions—for instance, by NATO, who invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty within twenty-four hours of the 9/11 attacks, its first since its inception.

Both President George W. Bush and Congress had a constitutional duty to defend and protect America—the country, the people, the institutions, its way of life—against destruction. These were repeatedly attacked before 2001, eliciting legal sanctions and limited airstrikes against targeted terrorist training camps. And so 9/11 came. To speak of America’s decision to commit to a muscular military response following 9/11 as an overreaction to a worse loss of life than the Pearl Harbor attack, as Hay does, might be a straightforward pronouncement, but it seems terribly simplistic. It arguably distorts the complex swirl of honor, duty, fear, and competing interests that always defines political activity and international relations, rendering the practice of politics an art and no exact science.

Rex Tremendae Majestatis

Hay writes of “September 11’s long shadow,” in illustration of how the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the ever-enlarging umbrella of the Global War on Terror was overcompensation for the supposedly isolated incident of 9/11. But a shadow can be of many kinds, distorting as much as revealing whole aspects and dimensions.

True, there have been no hijacked planes successfully turned into missiles against American cities since 9/11—but certainly not for a lack of trying. There was the December 2001 shoe bomb attempt by al-Qaeda operative Richard Reid on American Airlines Flight 63 to Miami; the August 2006 al-Qaeda plot to detonate liquid explosives on transatlantic aircraft; the infamous December 2009 attempt by al-Qaeda “panty bomber” Umar Farouk Abdulmatallab to blow up Northwest Airlines Flight 253 to Detroit; and the October 2010 al-Qaeda plastic-explosives bombing attempt on US-and Canada-bound UPS and FedEx cargo planes. Then there have been al-Qaeda -affiliated, -inspired, -imitated, -encouraged, or -aided terrorist events involving mass shootings, stabbings, and attempted truck bombings: the November 2009 Fort Hood shooting; the July 2015 Chattanooga recruiting center shootings; the June 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting; the October 2017 New York City truck attack; the December 2019 Naval Air Station Pensacola shooting. Nor should we forget the tragically successful 2004 Madrid train bombings or the July 2005 London bombings, which, while not directed to American soil, aimed at harming America in her military and other alliances. To the extent that these attempts were minimized in comparison with 9/11 was no sure thing, especially given what we’ve repeatedly heard of the often-laughable effectiveness of our security apparatus.

The absence of “another 9/11” since 9/11 we now know is greatly due to one thing: America going to war in Afghanistan. Having combed through nearly a hundred thousand of the 470,000 files the CIA declassified in 2017 from bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound, Nelly Lahoud recently summed this up in Foreign Affairs, showing how bin Laden’s 9/11 strategy was based on his calculation that America was no more than a paper tiger—he “never anticipated that the United States would go to war in response to the assault.” In fact, bin Laden had counted on Americans replicating the Vietnam War protests and demanding the government to withdraw from Muslim-majority countries. And thus bin Laden had no contingency plans for how to secure his organization, its operations, or even his own leadership of them on 9/12. Analyzing communications between al Qaeda members after America’s Afghanistan invasion, Lahoud writes that “for the rest of bin Laden’s life, the al Qaeda organization never recovered the ability to launch attacks abroad,” even though “its brand lived on through the deeds of groups that acted in its name.” But neither could these various groups organize effectively into one entity—their factionalism remains too severe.

It’s difficult to prove a negative, but it is surely important to consider along with the fact that there hasn’t yet been another 9/11 the political reasons why that might be so. America showed a political will to defend itself and to preserve itself after it was directly attacked. This resonated, and not just with America’s adversaries. And it introduced a certain sobriety into America’s post-Cold War fanciful political thinking, which, while certainly still deficient of seriousness (as events in Kabul most recently testify to), can now acknowledge that China is, for instance, more than a paper threat conjured up by conspiratorial war-loving Right Wingers.

Lacrimosa

At home, America’s response to the 9/11 attacks resonated within the generation of Americans then on the threshold of adulthood—the much-analyzed mysterious Millennials. Americans tend toward ritualistic displays of patriotism, but the Millennial Generation’s was no mere display: Millions of young men and women who’d previously never thought of national service volunteered to fight America’s post-9/11 wars, whether liberal or conservative, Democrat or Republican, or politically agnostic.

Since 9/11, 4.59 million men and women have served in the US military and have been discharged as veterans. Between 1.9 and 3.0 million have served directly “in theater” or indirectly “in-theater support” operations related to the post-9/11 wars. Over 7,000 US troops and over 8,000 US-affiliated military contractors have been killed. More than 53,000 troops have been wounded in action according to the Department of Defense, while the Department of Veteran Affairs has given official recognition of some degree of service-related disability to over 1.8 million post-9/11 veterans. Whether related to their service or not—the research is quite tricky here—there have been an additional 30,177 suicides among post-9/11 US service members and veterans since at least 2008. Globally, Brown University’s Costs of War project calculates that there have been between 173,000 and 177,000 National Military and Police, 12,468 Allied troops, and over 335,000 civilian direct war deaths since October 2001, with a total estimated 801,000 deaths related to the post-9/11 wars.

These are steep costs, and not just in terms of the lives lost, the millions of family members and friends affected, and the trillions of dollars in revenue that have been and will be paid out in benefits and care by the US (and other) government(s). Without in any way meaning to diminish the devastation these stark numbers represent, I believe it is no less important to honor the positive repercussions of these payments of sacrifice.

Two decades later, to no small degree, what this [9/11] has shown is how a free and equal people, even with a depressing lack of knowledge about the ways of freedom, equality, and democratic citizenship, still rose up to defend themselves, their compatriots, and their way of life.

Recordare

Nearly five million young Americans voluntarily signed up to give their life away for their country in the wake of 9/11, despite a widespread cultural and academic shaming of anything to do with the military since the days of the Vietnam War. They signed up, despite President Bush repeatedly admonishing the American people to keep on living life as though 9/11 hadn’t happened, to go to the mall and buy stuff and take lots of airplane trips. They signed up, despite America’s increasing boondoggling in the Middle East. They signed up, despite the rising numbers of deaths and injuries. They signed up, despite a public education system that increasingly portrayed patriotism as a problem, and decreasingly taught any type of civic education at all.

Much has been made of the trope that “America went to the mall while the military went to war”—that out of a nation of three hundred million-plus souls, less than one percent actually has served in the All Volunteer Force in a time of war. But is it really a surprise that Americans heeded official advice and haven’t paid much attention to America’s foreign wars over the past twenty years, given they were told not to? What is more remarkable, astounding even, is that despite all of these negative pressures, nearly five million young Americans still decided that serving their country was worth the possibility of their future. And their service has forced the country, and especially academic institutions, and even the Democratic Party, to question some of their prejudiced Vietnam-era holdovers.

It was because of 9/11 and post-9/11 veterans that the Ivy League—which famously banned them from campus in the ruckus surrounding the Vietnam War—finally started re-allowing ROTC to operate on their campuses. It was because of 9/11 and post-9/11 veterans that the Democratic Party began to think seriously again about issues of national security and war, after abandoning them to the Republican Party with their shutdown of Henry “Scoop” Jackson’s presidential bids in 1972 and 1976. And it was because of 9/11 and post-9/11 veterans that society at large has had to re-examine its prejudiced clichés about who serves in the military, when, and why; as well as about who the modern veteran is. It’s this cohort of military veterans who are forcing a reconsideration of veterans as social assets, rather than as just social deficits. To serve these new veterans, over 40,000 nonprofit civic organizations and associations have been formed since 2001. And among veterans themselves, their military service has contributed to their sustained civic and public engagement—research consistently shows that they are more likely to vote, volunteer, and assist their neighbors, than their civilian peers. They are also more likely to run for political office. Indeed, post-9/11 veterans have been running for Congress at relatively higher rates than did their Vietnam-era veteran peers, in closer imitation of the World War II generation.

All of these things contribute to the health of American democracy. In no small measure, because they force a reckoning with our national character, and with the deepest moral and political question of any polity: What makes it worth killing and dying for?

Liber Me

While we can know with some certainty the numbers of Americans who’ve joined the military in the wake of 9/11, we cannot know the exact numbers of the untold others who’ve chosen to pursue studies in politics, foreign affairs, history, and national security, or who’ve pursued careers as public servants, because of 9/11. We cannot know the exact numbers of further others, newly awakened to deep questions of national meaning and civic purpose, who explicitly became teachers after 9/11—hoping to strengthen and preserve the democratic spirit for another generation; to prevent such attacks and warfare in the future; to enable peace to flourish. But all this we know happened. I am one of these individuals; so too are at least two of my siblings; and so also are many of my professional peers.

Hostile attacks from a foreign enemy—war—necessitate some national self-evaluation and reflection. I believe that this in fact is one of the more powerful dynamics underneath the current acrimonious public campaigns about American history, civics, and identity. Well before 9/11, civic education advocates were worried about the hollowing out and diminishing of social studies and civic education in American classrooms, but by the turn of the millennium, as Chester E. Finn, Jr. relates in Where Did Social Studies Go Wrong?, many had turned to broader avenues of education reform, in despair at their lack of progress. The events of 9/11 changed that. The need for a robust civics education that could provide explanations for why some people abhor freedom and seek to obliterate democracy; why the United States is worth preserving and defending; and how our forebears responded to previous attacks upon their country in particular and freedom in general, convinced advocates at various institutions to reinvest in civic education reform.

As these efforts often have, there was a multiplying effect throughout the next two decades, which saw national institutions like the National Endowment for the Humanities and private outfits ranging from the Bill of Rights Institute to the Albert Shanker Institute embark on projects meant to reinvigorate civics teaching and learning. The Civics Renewal Network, the Leon and Amy Kass What So Proudly We Hail project, the American Enterprise Institute’s Program on American Citizenship (at which I formerly worked), iCivics, and Eric Liu’s Citizen University, among numerous others, all came after 9/11, fuelled by an awareness of the need to foster an engaged, attached, and responsible citizenry who understand who and what they are as a people and a nation. The latest, largest expression of this cross-partisan awareness is the NEH funded Education for American Democracy Initiative, which brought together a national network of more than 300 scholars, educators, practitioners, and students (myself included) to create a “roadmap” for history and civics studies, newly published earlier this year.

Few of these efforts are as profound, unanimous, flawless, or as widespread as many of their advocates would like them to be. Troubling trends persist, including the inability of the civic education community to define what, exactly, civic education is and ought to be. But surely their very existence speaks to an awareness of the vital importance of teaching civic virtue, responsibilities, and rights, for the health and preservation of the American regime.

Ingemisco

How ought a liberal nation-state to preserve its soul, and enable peace to flourish within its borders? And what enables a country to prosecute a war without losing its soul? Consigning political principles to memory and memorializing past events has never been enough to sustain civic unity, let alone a national unity of will and purpose, across an extended republic of fifty states harboring over three hundred million souls. What’s needed is a firm foundation of civic knowledge, civic attachment, and civic participation—what earlier generations called patriotism—to perpetuate the acknowledgement of a shared national identity.

Today, we lament the fleetingness of that acknowledgement so remarkably manifest after the 9/11 attacks, with few willing to excavate among its ruins to uncover the causes of its frailty. But even within that “civic moment,” Theda Skocpol was casting doubt in PS: Political Science and Politics on the ability of 9/11 and the War on Terror to “revitalize American civic democracy” as previous wars had done, because of the already crumbled infrastructure of civil society. This already existent civic weakness, she argued in 2002, was being further exasperated by a governing class who couldn’t or wouldn’t understand how to channel popular participation in a war effort, as previous generations had done.

For at least three decades before 9/11, the culture wars about America within America had been going strong, influenced by everything from LBJ’s Great Society programs and the Vietnam War to the sexual revolution, to the Clinton impeachment hearings, to the American flag. National identity and patriotism were key intertwined themes of these skirmishes, and the official tally was stark for traditional supporters: in 1990, forty-nine percent of respondents told Gallup that war was “outdated;” also by 1990, the Supreme Court had already struck down criminal laws against burning or defacing the American flag; by 2000 three Congresses had been too divided four times over to vote for a flag protection bill; an equally high amount of Americans believed the media “were too critical of America” as believed the media supported America; school boards around the country were having nationally-profiled fights about whether schools should be teaching that American culture, values, and opinions were good or preferable to other regimes, with many rescinding any such policies. Even though over seventy percent of Americans believed that patriotism was “very important” in 1998 (compared to only forty-three percent in the 1970s), the majority of the public believed that fewer and fewer of their fellow Americans were patriotic enough. But the problem seemed to be more about a lack of knowledge: No one seemed really to know what patriotism was, or whether different generations might express it differently.

This had its own effect on the vitality of civic associations and organizations. From the early 1800s until the 1960s, membership-based voluntary associations were at the center of American public life. “Leaders established civic reputations by helping to organize fellow citizens into membership groups,” Skocpol wrote in her PS article, and thus when national crises struck, “leaders knew how to mobilize fellow citizens, and there were well-worn institutional channels through which people could work together and pool resources.” But the Civil Rights and feminist movements radically changed the chapter-based membership federations that made up the muscle of US civic life, while the Vietnam War “rendered traditional patriotic associations less appealing to many Americans.” Furthermore, all of these civic associations were challenged by a new entrant to the scene in the 1970s and 1980s: professionally run and managed advocacy associations, which did not have individual members so much as lists of monetary contributors. Meanwhile, at the state and local level, nonprofit social agencies were also proliferating, which like advocacy groups, were professionally managed and raised money “from donors, government agencies, or mailing-list adherents, rather than from members who attend meetings and pay regular dues.”

What this meant is that on 9/11, there were few well-established channels through which individuals could volunteer together, and “fewer ways to link face-to-face activities in local communities to state and national projects.” Where historically in times of war and peace voluntary membership federations would join with local, state, and national public officials to pursue important public projects, in 2001 as in 2021, “partnerships between civic organizations and government are primarily a matter of collaborations among professionals.” And in fact, as Skocpol noted, after 9/11 and in the wake of the anthrax attacks later that month, officials “stressed managerial coordination and professional expertise.”

This reality helps makes sense of why after 9/11 American civic attitudes changed but American civic behavior barely did, outside of a huge jump in mass TV viewing. In the months after 9/11, the Christian Science Monitor asked: the American “public feels urge[d] to act—but how?”; the New York Times wondered: “Asking for Volunteers, Government Tries to Determine What They Will Do;” while the Wall Street Journal fully acknowledged a conundrum in “Waiting for the Call.” The hundreds of thousands of Americans who wanted to do something civically meaningful were essentially hung out to dry, with an excess of emotion and motivation and goodwill for them to somehow make sense of and expend. Is it any wonder, then, that in the ensuing two decades, these have developed even higher levels of government skepticism?

Lux Aeterna

After the 9/11 attacks on Americans on American soil, some gave their blood, some gave their life, and some gave of their talents to protect and preserve America for another generation. Some became teachers, and tended to preserving the soul of the nation through education; others became soldiers, and focused on defending the whole of the nation against hostile outside forces.

Two decades later, to no small degree, what this has shown is how a free and equal people, even with a depressing lack of knowledge about the ways of freedom, equality, and democratic citizenship, still rose up to defend themselves, their compatriots, and their way of life.

Twenty years later, America has endured, battered but like the flag on that revolutionary night, still there. This, we can honor, not mourn.