Terrorism Remains a Real Problem

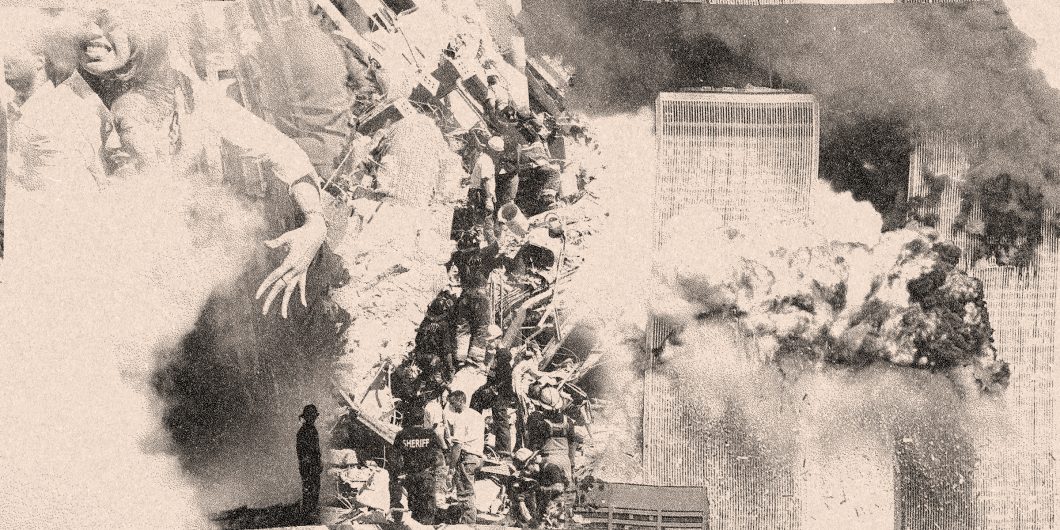

Will Hay argues that the United States overreacted to the terrorist attacks of 2001 and that the government’s policy choices made the world worse, not better. Hay blithely takes for granted that 9/11 was an aberration unlikely to recur—in part because the terrorists could only use the element of surprise once. In his view, the US can be faulted for “failing to recognize 9/11 as [a] uniquely horrible episode rather than the start of a new struggle.”

But 9/11 was not the only jihadist terrorist attack on the United States. In fact, there have been several attempted and near-successful jihadist attacks on the United States since 2001, including the shoe bomber in December 2001; a plot to detonate a dirty bomb in May 2002; a 2006 truck attack at UNC-Chapel Hill; the 2009 Fort Hood shooting; the underwear bomber in December 2009; the 2010 Times Square bomber; a conspiracy to bomb Arlington National Cemetery and the Pentagon in 2010; an attempt to bomb a pair of cargo planes in 2010; another 2010 car bomb attempt; the Boston Marathon Bombing in 2013; a beheading in Oklahoma in 2014; a hatchet attack in New York in 2014; a shooting in Texas in 2015; a shooting at military facilities in Tennessee in 2015; a stabbing at UC-Merced in 2015; the 2015 San Bernardino attack; the 2016 nightclub attack in Orlando; a series of bombings in New York and New Jersey in 2016; a car ramming in Ohio in 2016; a 2017 truck attack in Manhattan; and a shooting at a navy facility in Pensacola in 2019.

Hay might respond that these were all small compared to 9/11; that 9/11 was unique in its scale and ambition. But again, that is false. Jihadists have launched other large-scale or highly-visible terrorist attacks since 9/11, including a suicide attack on the Indian parliament in 2002; the Madrid train bombings in 2004; the 2005 bombings in London, Egypt, Indonesia, and Jordan; the 2008 three-day siege in Mumbai; 2010 bombings in Moscow and Lahore; the Christmas Day bombings in Nigeria in 2011; the shopping mall attack in Kenya in 2013; the Kano bombing in Nigeria in 2014; ISIS’s attack on Paris in 2015; the Palm Sunday attack in Egypt in 2017; a suicide bombing at a concert in Manchester in 2017; and a series of coordinated attacks in Barcelona in 2017.

I do not apologize for belaboring the point with these long lists: chances are most readers, probably including Hay, have forgotten or were never aware of all these attacks and thus have not seen the continuing narrative they imply. Fortunately, some scholars and analysts continue to track terrorism and jihadism and provide resources for the rest of us to understand the threat.

Hay can only argue that 9/11 is unique if he is looking at “successful, mass-casualty highly-visible, jihadist-inspired attacks inside the United States” and discounts attacks elsewhere in the world and smaller scale attacks. When you narrow the filtering criteria so restrictively, it is easy to winnow down the cases and present 9/11 as an aberration rather than what it truly was: the most successful attack in a decades-long decentralized transnational terrorist campaign that is still ongoing. Jihadist groups are thriving across the world. Seth Jones of the Center for Strategic and International Studies estimated in 2018 that there were up to 270 percent more jihadist fighters around the world than in 2001—at or near an all-time high at least since 1980, when the dataset begins. Jihadist groups are more popular, more widespread, and more powerful today than at any point since 2001, as demonstrated by how tenaciously the Islamic State, al-Qaida, and the Taliban have continued fighting.

A critic may argue that jihadists are so prevalent precisely because of US foreign policy choices; that we are creating our own enemy. That line of argument denies the agency of terrorists, who make their own choices regardless of what the US does, and it exaggerates the importance of the United States, as if we are responsible for everything that happens in the world. As illustrated above, much of the jihadist campaign is not directed at the US, and it has happened before, during, and after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

That the jihadist campaign is ongoing means that the funding increases and new authorities given to the intelligence and homeland security bureaucracies since 2001 is at least partly justified. But Hay gives them no credit. Hay complains about the supposed overreach of US intelligence and homeland security activity since 9/11. But Hay is trying to have his cake and eat it too: he celebrates the absence of further large-scale attacks within the United States, then damns the homeland security and intelligence apparatus that helped ensure their absence. The absence of successful large-scale follow-up attacks was not a foregone conclusion, and Hay overlooks how US policy choices after 9/11 helped forestall them.

Hay might at least consider the counterfactual: if the United States had not responded the way it did, more 9/11s would have been more likely to happen. That does not justify every choice and every policy since 2001, but neither does the absence of another 9/11 in the United States mean every policy was worthless. Instead, Hay cynically implies, with no evidence, that people whose careers and contracts depended on fighting terrorism hyped the risk to keep the money flowing, thus denigrating the patriotism, honesty, and service of those who gave years of their lives to fight a war he now thinks was unnecessary. I would not begrudge public servants if, in response to Hay’s libel, they channeled Col. Jessup in A Few Good Men: “I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very freedom that I provide and then questions the manner in which I provide it.”

Hay goes on to criticize the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which is de rigueur now that both wars are over and most people consider them failures. He doesn’t make much of an effort to analyze the cause of either war’s failings other than to say that, “The problem involved being drawn too deeply into open ended commitments with an ill-defined war on terrorism,” and, regarding Afghanistan, that “Mission creep… squandered early success and turned nation building into a counterinsurgency that became America’s longest war.”

The problem in Iraq and Afghanistan was not mission creep, or open-endedness, or state building. One of the chief problems was choosing to fight a second war before finishing the first, which few now dispute. Another is simply that the US never gave either war the sort of resources required to achieve its ambitious aims.

I’m not convinced this is the best way to understand our failures in those wars. He says they were “open-ended,” but what war isn’t? World War II was open-ended in that we did not know how long it would last or when or how it would end. To stay with the analogy, the postwar occupation of Germany was certainly open-ended in that it was hard to define the end-state we were aiming for or describe exactly when we would transfer sovereignty back to the Germans (which took four years) or when US forces would leave (they never have). World War II looms large in the American understanding of war because it feels so clear-cut and simple, with demands for unconditional surrender and V-E and V-J dates to celebrate the war’s end. That clarity is an illusion; most military operations do not start or stop that way, in part because we strive to avoid World War II’s levels of indiscriminate violence that were apparently necessary to bring about that war’s abrupt end.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had clear goals which necessarily included some measure of state building. What Hay characterizes as “mission creep” and “ill-defined” missions were essential from the beginning. In Iraq, the US aimed to depose Saddam Hussein because of his refusal to abide by his disarmament commitments; in Afghanistan, to deny safe haven to al-Qaida in Afghanistan. Neither could be accomplished without stability operations and reconstruction and development. The rapid collapse of the Taliban and al-Qaeda’s apparent loss of safe haven were important successes, but it was obvious that these gains would be quickly reversed if the United States left without helping reconstitute an Afghan state and Afghan security forces capable of operating independently (as recent weeks sadly demonstrate). Helping Afghanistan was not charity; it was strategy. Similarly, the United States was obligated under international law to help reconstitute some kind of authority in Iraq after deposing its government. To topple a regime and leave would have been both immoral and strategically idiotic (as later demonstrated by NATO’s operation in Libya in 2011).

The problem in Iraq and Afghanistan was not mission creep, or open-endedness, or state building. One of the chief problems was choosing to fight a second war before finishing the first, which few now dispute. Another is simply that the US never gave either war the sort of resources required to achieve its ambitious aims, whether by underfunding reconstructing, preferring a “light footprint” in military deployments, or undercutting those deployments with preset, publicly-announced withdrawal deadlines. Those were not the only problems, and shelves will be filled with later retrospectives, but acknowledging those realities would be a helpful starting point.

Hay will doubtless disagree with my argument that the wars needed more time, money, and troops because, in his view, the wars already took up too much time and resources, distracting the United States away from other priorities. He manages to blame everything from the rise of China, the opioid crisis, deindustrialization, and the 2008 financial crisis on the wars because, he says, they distracted the US and crowded out the budget. Reading Hay’s litany of woes, one gets the sense that, for him, “Everything I don’t like is post-9/11 foreign policy.” There is much to criticize in the US’s response to 9/11, but Hay undercuts his case by overstating it so crudely.