Current interpretations of the First Amendment may sometimes serve as a bulwark for cancel culture, not a remedy.

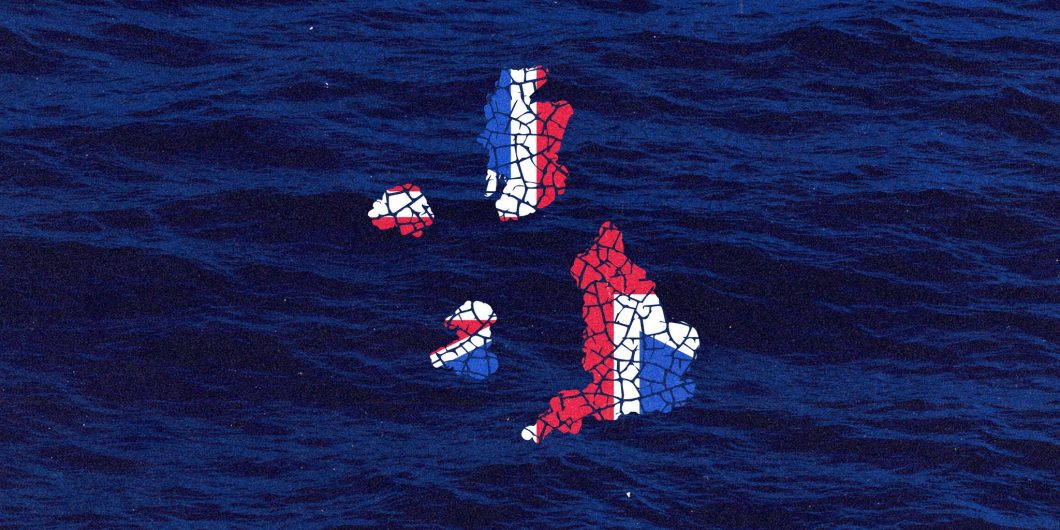

The Divided Kingdom?

“The difference between Americans and Britons,” my father always said, “is that Americans think 100 years is old, while we think 100 miles is far.”

This quip is true, in large part, because it’s quite easy to travel 100 miles in the UK and land in another country. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is a country of countries. All four “home nations” have storied pasts stretching back millennia; different cultures; distinctive religious traditions. And all four have experienced serious historical conflict against each other. In one case—Wales—there’s also a widely spoken language only distantly related to the tongue commonly used in the other three.

This makes the maintenance of unity and manifestations of civic nationalism genuinely fraught, something long known but grievously exposed first by 2014’s referendum on Scottish independence, then by Leave’s victory in the 2016 Brexit Referendum, and finally by a Conservative landslide in the December 2019 general election.

Of course, there were rumblings beforehand, made worse many times over thanks to Labour’s 1998 programme of devolution. This tinkering birthed a constitutional Frankenstein, neither flesh nor fowl nor good red herring: it only looks like the sort of governance arrangements familiar to Australians or Americans. It’s actually “NQF”: Not Quite Federalism.

As in true federal systems, devolution provides for different laws and legal systems in each home nation (see, famously, Scotland and Scots law). However, because it burst fully formed from a unitary state’s chest, the various home nation administrations discovered during the pandemic they could not close what are in fact national borders—unlike mere states in federal Australia, which did so repeatedly.

This gimcrack system of quasi-federalism nonetheless contained within it acorns that, if allowed to mature into mighty oaks, could fracture the union.

Scotland

That devolution was designed by people who, also in my father’s words, “hadn’t bothered to think their thoughts through to the end,” first became plain in May 2011, almost a year to the day after I moved to Edinburgh. The Scottish National Party (SNP) won a parliamentary majority in the Holyrood elections. This, of course, was supposed to be impossible. Scotland’s electoral system—which formed part of the devolution settlement set out in the Scotland Act 1998—was designed to prevent majorities.

The 2011 result meant a referendum on Scottish independence became inevitable, although it was clear that achieving a “yes” to independence was always going to be a struggle. Not only did many people vote SNP in 2011 because they were furious with Scotland’s other political parties (especially Labour), thanks to the country’s idiosyncratic electoral boundaries, the SNP won a majority of seats (53.49 percent) with a plurality of the popular vote (44.04 percent).

My first inkling that the debate over 2014’s “Indyref”—as it came to be called—had compromised Scotland’s historically benign civic nationalism was when, while working as a lawyer at a commercial law firm, the partners told the rest of us not to take a public stance on the vote. Potential clients were starting to choose their advisers based on which way the firm in question was perceived to lean on independence. At first, I thought it was just my firm, but word filtered back to me from friends in other firms: they’d received the same instruction, too.

Soon after, the polls began to narrow. Indyref debates around the country—once merely well attended—filled to overflowing. There was violence in Glasgow. The numbers registering to vote rose to unprecedented levels. People were warned of long lines at polling places. Turnout on 18 September 2014 was 85 percent, the highest recorded since 1910’s People’s Budget election, an earlier moment of constitutional crisis.

Yes, independence was defeated 55 to 45, although the defeat took a particular form: the “No” vote had its strongest roots in people who wanted to remain in both the European Union and the United Kingdom, while the bulk of the “Yes” vote turned on a vision of “an Independent Scotland in the European Union”.

Then, Leave won the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union. Perhaps out of sheer cussedness, the home nations went in different directions—England and Wales for Leave, England strongly so (53.41 per cent), while Scotland and Northern Ireland plumped for Remain, Scotland overwhelmingly so (62 per cent). Scotland’s huge support for Remain eclipsed even that in London. However, England’s population relative to the other three home nations meant Scotland’s vote, effectively, did not count.

Going back to 1998, this population gulf contributed to Blair’s choice of devolution as opposed to federalism. California and New South Wales are populous states relative to the total US and Australian populations, but neither dominates in the same way England dominates the United Kingdom. Giving tiny Scotland the same number of representatives as England in an elected upper chamber modelled on the Australian or American senate would put the famous West Lothian question on steroids.

The Leave-Remain gulf between England and Scotland became even more marked in the wake of December 2019’s Conservative landslide. Boris Johnson’s Tories turned all their opponents into mincemeat in England and Wales. Meanwhile, in Scotland, the SNP won 48 of 59 available Westminster constituencies, reducing Labour to a single seat and Conservatives and LibDems combined to less than a cricket team.

Continued electoral success for the SNP since 2019, including in May’s local elections, has elicited repeated calls for another independence referendum next year, something wholly in Westminster’s gift. During the pandemic, there was a lengthy period when support for independence enjoyed an extended poll lead over support for the union. Unsurprisingly, this is when calls for a second vote were loudest. Boris Johnson’s response, to be fair, has been simplicity itself: No.

That said—like many other world leaders—First Minister Nicola Sturgeon was enjoying a coronavirus-fuelled rally effect, and rally effects seldom last. Australia’s Scott Morrison, the US’s Donald Trump, and Boris himself all received similar electoral boosts. Morrison and Trump are no longer in office, while Boris is experiencing a combination of the usual mid-term polling doldrums with widespread public anger over his personal hypocrisy (“do as I say and not as I do”) when it comes to compliance with his own government’s coronavirus legislation.

The latter not only hit the government in the polls: MPs were deluged with complaints from constituents about a widespread culture of impunity among the great and good when it comes to the rule of law in Britain. Journalists (who are supposed to hold politicians to account) have also been implicated, as has the leader of the opposition.

In early June, the pressure built up such a head of steam Boris was subjected to an internal, Tory MPs’ confidence vote. He survived, 211 votes to 148. For reference, Theresa May’s equivalent figure in December 2018 (with fewer MPs, obviously) was 200 to 117. May only lasted another six months, finally resigning in the wake of the Tories collapsing to nine per cent in the 2019 European Parliament elections. More generally, the history of Conservative PMs who alienate their own MPs is not good. That said, Boris isn’t called “the greased piglet” for nothing.

On the wider question of Scottish independence, all the concerns from 2014 are still in play. They are, in no particular order: oil, EU membership, currency, and pensions.

The SNP campaigned over many years for a greater return of North Sea oil and gas revenues to Scotland (91 percent falls into Scottish territorial waters). Recent scaremongering about the North Sea running out of oil and gas fails to recognise that oil fields remain productive at the margins while oil prices remain high. That it is more difficult to recover the resource matters little when there is still money to be made.

That said, “It’s Scotland’s Oil” as a campaign slogan is harder to deploy for a government keen to burnish its green credentials. This remains true despite war in Ukraine putting the anti-fossil fuel wing of the global environment movement on the back foot. Relatedly, Sturgeon is in the process of discovering that the SNP’s hostility to Trident, the UK’s nuclear deterrent, does not play well with continued NATO membership.

When it comes to the EU, it seems that an independent Scotland could eventually accede, but eventually is the key word. Many EU member states require referendums in their own countries before the bloc can admit a new country, and no member state of the EU has previously broken up with the smaller bit then applying to join the bloc.

This leaves lawyers in Brussels short of precedents and burdened by Spain’s own serious separatist movements. Inspired in part by the Scots, the Catalans did try to make a run for it, holding an unauthorised “wildcat” referendum on 1 October 2017. The extent to which Madrid flattened Catalonia’s pro-independence leadership afterwards was notable; the SNP is unlikely to repeat Catalonia’s mistake.

Both Labour and Conservative Parties have rejected currency union with an independent Scotland, which means the SNP advocates sterlingisation as an alternative. This would mean Scotland—much as Panama does with the U.S. dollar—using the pound without England’s permission. Scotland would be without a central bank or a lender of last resort. Sterlingisation would undermine the SNP’s plans for a social-democratic (and debt-fuelled) nation. Austerity would be swift and severe, any socialism followed by an aggressive move to free markets and deregulation. This may be no bad thing, but it probably isn’t what most independence supporters have in mind.

Constitutions—even written ones—aren’t just words. They are conventions, and time, and interpretations, and practice. You don’t find out how they work until you have used them for a while.

While oil, EU membership, and currency have been central to the debate for decades, the sheer scale of the pension crisis, both as it applies to the UK as a whole and a putative independent Scotland, came to the fore in 2014 and stayed there. Americans often expectorate about their country’s social security black hole, but the UK’s is also impressively deep. The state pension is a genuine Ponzi scheme, for starters: current revenues are paying for current entitlements, combined with an ever-growing pool of recipients.

Within the UK, Scotland’s position is worse: its population is both older and sicker than that of England and Wales. The crisis would bite sooner, with public sector net borrowing (what needs to be borrowed over and above tax revenues) rising from 4 percent this decade to around 10 percent by mid-century. In short order, public debt would rise to 200 percent of GDP. That’s a larger hole than the one Greece is in. And if there is one thing that is certain, the EU does not want to admit a Tartan Greece as German military expenditure goes through the roof.

On the back of the 2014 and 2016 referendums and 2019 general election, UK unity debates have focussed on Scotland. This isn’t just because Scotland has a well-resourced independence movement with an entrenched political party able to make its case. It’s also because Scotland is closer to English hearts: large majorities in England want Scotland to stay in the UK. The country is probably helped by its fascinating (partly) shared history, beautiful countryside, and a landscape dotted with castles.

Unfortunately, this has had the effect of ensuring the home nation that really could blow up the United Kingdom—Northern Ireland—is reduced to bit player status. Meanwhile, Wales—the only home nation to make a success of devolution—has the lessons it offers ignored.

Northern Ireland

In the wake of 41 percent of his own MPs telling him they want him gone, Boris has said he will bring forward legislation abrogating the Northern Ireland Protocol agreed with the EU as part of Brexit. Let me explain.

Under the terms of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, power must be shared between the two largest political groups elected to the Northern Irish Assembly in Stormont, which has thus far been made up of blocs identifying as unionist and nationalist. Until those that declare themselves “other” finish in the top two, it doesn’t matter whether a nationalist or unionist party finishes first or second, because they must share power.

It’s for this reason that Sinn Féin’s emergence as the overall largest party in May’s elections was not the political earthquake many overseas observers thought. A sizable majority of the electorate is still in favour of staying part of the United Kingdom rather than joining the Republic of Ireland, and Northern Ireland works only when both its nationalist and unionist communities consent to the system governing it. In that sense, political and constitutional reality is unchanged.

The Good Friday Agreement was also drafted on the understanding that both Ireland and the UK were part of the EU, so it didn’t envisage what either country’s commitments would be in relation to the border they share in the event of either leaving. Relatedly, it also never envisaged the emergence of a party like the third-way Alliance, which argues that bread-and-butter issues matter more than unionism or nationalism. But after May’s elections, it is now a genuine force in Northern Irish politics. Despite these wrinkles, the Good Friday Agreement has become something of a foreign policy koala, which everyone claims to protect.

To quote Bernard Woolley of Yes, Minister fame: “Ireland doesn’t make it any better; Ireland doesn’t make anything any better.” In the days before devolution sought to confer power on Stormont, to be appointed Secretary of State for Northern Ireland was like spending a season in Purgatory. Posh pagan Romans sent to govern the restive monotheistic province of Judaea must have felt similarly, wondering who they’d offended in the Senate or Imperial Household. One of the most effective bits of British television in recent years cast Ballymena native James Nesbitt as Pontius Pilate in a BBC version of the last week in the life of Jesus. One of the reasons it worked so well was Nesbitt’s decision to speak the Roman’s lines in his distinctive accent.

Like ancient Judaea, Northern Ireland is a place of serious and barely repressed sectarian conflict. Keeping the peace there requires an artful blend of compromise and good faith. Now, you could argue that the colonisation of the Ulster Plantation and surrounding counties was a terrible and immoral mistake, and the Irish border problem is punishment for the sins of our ancestors. Northern Ireland became the UK’s cat-flap of doom, simply because the EU was (rightly) concerned that importers would use it as backdoor into the customs union. It was clear from at least the 2017 General Election (and probably before) the Europeans were wholly inflexible on this point. However, that very inflexibility means the EU has now bought shares in Stormont it will be unable to sell.

The Good Friday Agreement has its most direct effect on the future of the Northern Ireland Protocol agreed upon by the United Kingdom and the European Union in 2019 as part of Brexit. As a result, there is now a trade-and-customs border between Northern Ireland and mainland Great Britain (that is, within the same country), to avoid one being imposed between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (that is, between two different states that share the same island). Ever since, Northern Ireland’s unionist parties have fiercely resisted the Protocol, arguing it’s unfair because it prioritises the wishes of one community in Northern Ireland (nationalists) over the other (unionists).

They argue that a trade border in the Irish Sea not only subjects Northern Ireland to different regulations from the rest of the United Kingdom, but those regulations emanate from a political entity of which the UK is not a part. Unionists claim (with some justification) an arrangement like this is incompatible with Northern Ireland remaining a sovereign part of the UK.

And how did this come about? Because the EU has hard borders with what EU treaties call “third countries.” After Brexit, the UK became a third country, which means the logical consequence was a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Except a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland is not possible, a provision written into the Good Friday Agreement. Based on referendums in both Northern Ireland and Ireland, and partly an international treaty and partly a contractual agreement between the parties, it isn’t part of UK domestic law, but it binds us in so many areas it may as well be. It also guarantees Northern Ireland access to the European Court of Human Rights—a major reason David Cameron couldn’t repeal the Blair-era Human Rights Act.

From the EU’s perspective, Brexit was always more of an excommunication than a divorce: you can’t take the sacraments, but you’re still not allowed to sin. And once you’re sufficiently contrite, the process can be reversed, but only on European terms. It’s been as delusional as the most doctrinaire Brexiteer in its belief that Northern Ireland is an issue that can somehow be solved in law, codified, and fixed without the consent of the communities living there.

At the time of writing, unionists are refusing to share power with nationalists and so robbing Northern Ireland of a government until the Protocol is modified to their satisfaction. Meanwhile, as mentioned, Boris is threatening unilateral abrogation of bits of it. The EU response thus far has been to threaten to blow up the entire trade agreement negotiated in the wake of Brexit.

Both major parties on the British mainland—but especially the (allegedly) pro-union Tories—are also implicated in this mess. They were too busy looking at Scotland, with its clear post-2014 political realignment into Yes or No on the question of independence. I’ve lost count of the number of people I’ve told (often to considerable surprise) that Labour doesn’t stand candidates in Northern Ireland, for example, or that the various pro-union parties are all more conservative than the Conservatives, leaving left-leaning unionists nowhere to go other than the Alliance, which pointedly doesn’t have a view.

Northern Ireland also has fewer English friends than Scotland; its loyal unionists rightly fear being thrown over not only in favour of the storied kingdom in the North but in favour of England’s economic interests. Boris is not seeking to remove the internal border, only to mitigate its effects. A lot of English people would flick Northern Ireland off like a scab; after all, when you really hate Ireland, you give it Northern Ireland. If Northern Ireland as a functioning part of the UK while still in part subject to EU rules is the aim, then to adapt the old Irish joke, we wouldn’t be starting from here.

Wales

Wales is the least like England of the “other” three home nations, and yet like England, it voted Leave. It has been ruled from London the longest (since 1282) but retains its cultural distinctiveness. It has a nationalist party, Plaid Cymru—often dismissed as a poundshop SNP—whose very hybrid name is revealing. In Wales, people switch languages so rhythmically—especially outside Cardiff, the capital, where English dominates—your ears are lulled by sing-song waves of English and Welsh; Welsh is the only Celtic language UNESCO considers not endangered. The country’s most popular sporting code is not (round ball) football but (egg-shaped ball) rugby union. Its greatest modern politician, David Lloyd George, advocated federalism as long ago as 1895. One suspects Wales could copy Australia’s system and make a fair fist of it.

Of course, coronavirus made fools of governments everywhere. It was Wales’s Labour First Minister, Mark Drakeford, who realised devolution and federalism are not the same thing when he tried to close Welsh borders at the height of the pandemic and discovered the UK is still a unitary state. Drakeford’s silliness aside, however, Wales has functional politics. There is no nationalist monolith, as in Scotland; Welsh Labour voters who voted Leave have navigated their differences with Westminster Labour skilfully; there is no “natural party of government.” Labour, Tories, and Plaid Cymru duke it out in public and the electorate respects the results, whatever they may be. If Labour wanted to foreground a devolutionary success story, Wales would be it. One out of three is something, I suppose.

Constitutions—even written ones—aren’t just words. They are conventions, and time, and interpretations, and practice. You don’t find out how they work until you have used them for a while. Changing them is dangerous. The desire to modernise for its own sake (which Tony Blair had in spades) is always going to create all sorts of unintended consequences. Nicola Sturgeon is still angling for another independence referendum next year. Northern Ireland requires an almighty fudge, and if other entities (UK, Ireland, and the EU) try to crystallise that fudge, troubles may ensue. Bits of the various devolution settlements probably need to be unwound.

The kingdom is divided now, and its future is shrouded in mist.