Is James Bond now part of today's culture of toxic masculinity?

Free Trade Lessons from the British Empire

Market liberalism is taking a battering these days. Across the world, intellectual critiques and political condemnations of free trade are surging. This is having an effect: Some surveys of American opinion suggest that free trade’s popularity underwent a sharp decline over the past year, especially on the right and among self-described independents.

While there are many reasons for resurgent skepticism about free trade, it’s worth noting that, from a long-term historical standpoint, free trade has generally struggled to win hearts and minds. Following World War II, there was a certain consensus among Western policymakers about the desirability of trade liberalization, even if it was pursued haphazardly and inconsistently. Since the late-15th century, however, mercantilist and protectionist policies have been the norm rather than the exception.

One reason for this is that while protectionism makes consumers pay more for lower quality goods, tariffs and import quotas directly benefit those companies who resent the disciplines of competition, whether domestic or foreign. Moreover, unlike consumers, such businesses have the resources, political contacts, and incentives to lobby legislators and governments for preferential treatment. Ergo, special interests tend to prevail in trade policy debates, even if most people happen to favor greater trade liberalization.

There are, however, some instances in which those intent on protecting their privileges (invariably dressed up in the garb of common good rhetoric) have found themselves on the losing side. Nineteenth-century Britain is such a case. The remarkable success of free traders in advancing their agenda in Britain from the 1840s onwards still provides today’s market liberals with valuable lessons about how to overcome protectionism and extend the reach of economic liberty.

Liberating Trade in an Age of Reform

The middle decades of 19th-century Britain are often portrayed as an age of liberal reform. Slavery’s abolition in 1833, the Reform Acts of 1832 and 1867 which widened the electoral franchise, as well as Catholic and Jewish emancipation in 1829 and 1858 all transformed Britain’s constitutional, political, and legal landscape. Likewise, the 1846 repeal of the tariffs and other measures which restricted food imports into Britain and kept food prices high—colloquially known as the Corn Laws—is often portrayed as a decisive blow to the mercantilist practices which had dominated the British economy since the 17th century.

Mercantilism’s intellectual respectability had been badly hurt by Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations in the late-18th century. The 1786 Anglo-French Commercial Treaty, spurred on by Prime Minister William Pitt, a great admirer of Smith’s work, also provided a blueprint for future trade liberalization. Protectionist policies, however, returned with a vengeance in the wake of the post-Napoleonic war depression which roughly lasted from 1815 to 1821.

Successive Tory and Whig governments sought to wind back protectionist measures here and there, but were handicapped by the fact that many of their supporters—especially large landowners from all parties—were dead-set against anything that threatened their grip on the lucrative food supply. In the end, the Tory Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel was only able to get his Bill of Repeal (Importation Act 1846) through Parliament by relying on a coalition of the Whig opposition and a minority of Tory free trade MPs.

Considerable mythology surrounds the repeal of the Corn Laws. It didn’t, for example, lead to Britain embracing unilateral free trade. A small number of tariffs continued to be levied on important consumables such as wine. Nor did Britain hesitate to use remaining tariffs as bargaining chips during trade negotiations. That includes the 1860 Treaty of Commerce between Britain and Napoleon III’s France which has good claim to being the key event that ignited wider trade liberalizations throughout Europe like the Franco-Prussian Treaty (1862), the Italo-French Treaty (1862), the Anglo-Italian Treaty (1863), the Anglo-Zollverein Treaty (1865), and the Sweden-Norway-Zollverein Treaty (1865).

What’s not in question is the decisive shift in the climate of opinion in Britain about trade that occurred during these decades. Leading Whig, Radical, Tory, and Liberal politicians, important members of the Royal Family like Prince Albert, prominent aristocrats, key civil servants (especially in powerful departments like the Treasury), university economists, religious leaders (particularly low-church evangelicals), influential journalists, and many ordinary Britons—including the growing industrial working-class—rallied behind the free trade cause.

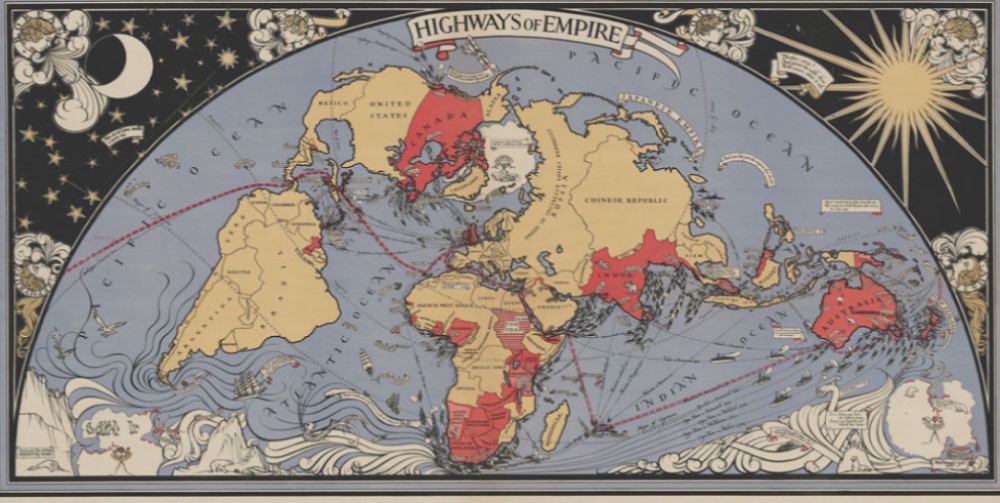

To be sure, internal opposition never completely disappeared. Several self-governing British colonies throughout the Empire, particularly in Canada and Australia, also maintained protectionist policies, despite London’s efforts to persuade them to the contrary. Yet not even the Long Depression of 1873-1896 which saw countries like Germany and France swing back towards protectionism could overturn the widespread free trade consensus in Britain. It wasn’t until the 1919-1926 postwar slump and then the Great Depression that political support for free trade broke down and “Imperial Preference” policies, based on the principle “home producers first, empire producers second, and foreign producers last,” were introduced by the National Government in 1932.

Forging the Free Trade Consensus

It may surprise some to learn that all of Britain’s Labour Party MPs voted against Neville Chamberlain’s protectionist Import Duties Act of 1932. Though Clement Attlee insisted that Britain needed to embrace economic planning, the future Labour Prime Minister was especially vocal in denouncing the Act. Echoing Adam Smith, Attlee maintained that tariffs are “a very ineffective weapon” which “should be utilized only if . . . used in pursuit of some definite and clear policy,” like trying to get others to open their markets. Chamberlain’s whole scheme, Attlee added, amounted to “a very large dole to separate industries.” It would also, he said, “corrupt political life” and “raise up a host of vested interests.”

One reason why free traders were so effective in rallying different constituencies to their cause was their careful tailoring of particular messages for specific audiences.

That’s quite an indictment. But the fact that a committed socialist like Attlee had so thoroughly absorbed these anti-protectionist arguments testifies to the long-term imprint left by Britain’s 19th-century free traders upon British economic culture. Free traders managed to make their position intellectually compelling, politically attractive, and, perhaps above all, popular among the wider population who weren’t likely ever to read Adam Smith’s or David Ricardo’s ruminations on the topic.

On the academic front, the teaching of political economy in Victorian Oxbridge, Scotland’s ancient four universities, and the new colleges that began opening throughout Britain from the 1830s onwards reflected a deep commitment to free trade. Instruction in economics—whether through newly-established chairs of political economy, through faculties of law and history, or through the Oxbridge classical “Greats” degree taken by many aspiring future civil servants, diplomats, and MPs—was invariably critical of mercantilism’s political and economic effects.

The intellectual case for free trade was also taken beyond the universities to those who held important political and economic positions. Since 1821, the highly influential Political Economy Club had brought prominent civil servants, industrialists, and City of London bankers into regular contact with scholars who favored free trade. Many of these academics also sought to shape working-class opinion through the university extension movement and by promoting publications like the trade unionist George Potter’s The Working Man’s View of Free Trade (1881). By the 19th century’s last quarter, trade unions had become bastions of free trade opinion.

Strategy Matters

One reason why free traders were so effective in rallying these different constituencies to their cause was their careful tailoring of particular messages for specific audiences. While they emphasized to working-class leaders how free trade lowered the price of staples like food and clothing, the same free trade advocates stressed to reform-minded Tories, Whigs, and Liberals that free trade would help liberate Parliament and the Government from the influence of special interests. Judging from his diaries, Sir Robert Peel was eventually persuaded to support repeal of the Corn Laws because he concluded that free trade would make the state less susceptible to “Old Corruption” (the selling of offices, sinecures, and pensions), less subservient to particular economic sectors, less beholden to specific lobbies, and therefore stronger and freer to focus on what governments should do.

It’s impossible, however, to understand free trade’s ascendency in Britain without referencing the figure of Richard Cobden (1804-1865). A successful merchant who was elected to Parliament as a Radical and then Liberal MP, Cobden was an especially effective proselytizer for free trade, whether speaking in Parliament, negotiating a commercial treaty with French officials, or addressing mass audiences in Russia, Spain, Italy, France, and Germany. He possessed the rare gift of being able to translate complex economic logic into language that non-specialists could grasp.

But Cobden’s rhetorical talents were surpassed by his other great skill: strategy. Having helped build the Anti-Corn Law League into Britain’s most widespread anti-protectionist movement, Cobden thought carefully about how the League might sway both elite and public opinion. He considered it just as important to arrange for the printing and distribution of thousands of pro-free trade pamphlets, articles, and speeches to broad audiences (especially before elections!) as it was to engage directly cabinet ministers, MPs, and Treasury officials.

Cobden’s strategy also involved persuading the League to adopt tactics and rhetoric used by the anti-slavery movement. Like the abolitionists, Cobden cleverly associated free trade with two causes very popular in mid-19th century Victorian England: moral reform and evangelical religion. That helps to explain why free trade acquired such a strong following among Liberals, Whigs, reformist Tories, those working in the City of London, the professions, and the growing service sector. In all these circles, low-church evangelicalism was a force to be reckoned with. They responded well to images of free trade cleansing the economy of privileges, reforming public finances, and diminishing poverty through economic growth.

Overcoming the Diffusion Problem

But what might this history mean for the free trade cause in our time? Perhaps the greatest lesson is that by educating but also rallying and organizing elite and popular opinion at every level of society, Britain’s free traders overcame the problem that those who favor free trade are usually dispersed and disorganized. They thereby cancelled out the normal political advantages enjoyed by protectionism’s proponents.

There’s no shortage of free traders in America today. While over a third of the U.S. population now regards foreign trade as an outright threat to the U.S. economy, the same surveys indicate that a majority of Americans continue to lean toward free trade rather than protectionism. The fact, however, that American trade policy has shifted in more protectionist directions since 2016 indicates that free traders have failed to mobilize pro-free trade sentiments among Americans.

American free traders should recognize that it is not enough to win the intellectual argument and persuade policymakers. Legislators and governments may well understand and lament all the problems of protectionism. That, however, has not dented the remarkable effectiveness of economic sectors such as the American steel and sugar industries at maintaining and even extending their protectionist privileges at the expense of the thousands of Americans businesses who use steel and the millions of Americans who consume sugar.

Unless free traders find ways to marshal and then concentrate the political clout of Americans who claim to favor further liberalizations of trade, I suspect that such industries will continue to get their way. That is bad news for those American businesses who benefit from cheap imports as well as American consumers forced to pay higher prices. The good news from 19th-century Britain is that it doesn’t have to be this way at all.