Getting Played by Venezuela

On January 26, the Venezuelan judiciary made an unsurprising announcement. Despite the agreements signed in October with the US government and the Venezuela opposition, the presidential opposition candidate, María Corina Machado, would not be allowed to run for the presidency. Machado, a center-right former legislator, won the primary election in October, taking 90% of the vote over other opposition candidates. However, the government had imposed an administrative ban on Machado for 15 years, preventing her from running for political office.

The result was predictable, but the US government insisted that the October agreement signed in Barbados (widely referred to as “the Barbados agreement”) would allow Machado to run and be a positive step toward free and fair elections in the country. They also insisted sanctions would return if Venezuela did not do its part.

Hope, of course, was unfounded.

Said agreements between the government and the opposition, with the support of the US, signaled a potential revision of the ban against Machado and other opposition politicians, while the US eased sanctions against the Venezuelan government, especially against the oil and mining sectors. The US did its part, going so far as to free Alex Saab, a Colombian-Venezuelan, who was jailed, first in Cabo Verde in 2020, and then in the US after his extradition in 2021. Saab had been accused of leading a multinational money-laundering operation on behalf of the Venezuelan government for its drug trafficking operations.

The US lifted significant sanctions on the Venezuelan oil, gas, and mining industries. OFAC authorized all transactions related to the Venezuelan oil and gas industries, including production, extraction, sale, and exportation of Venezuelan oil and gas, all kinds of payments for goods and services related to the oil and gas industries in Venezuela, new investments in the sector, and payment in form of oil and gas to creditors of the Venezuelan government.

Therefore, the lifting of sanctions made a significant difference to foreign companies in the oil industry in Venezuela such as Repsol, ENI, and Chevron, who had a hard time continuing their operations in the country with the sanctions. It also promised to increase oil production in Venezuela and thus improve the economic situation in a country highly dependent on oil exports.

The Fall of Barbados

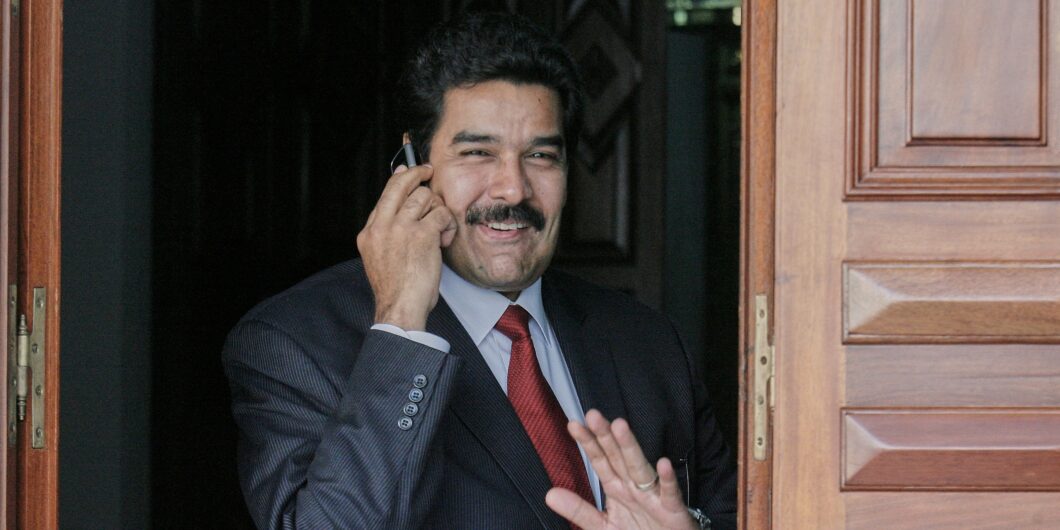

Three months after the agreement, President Nicolás Maduro has shown his true colors for the umpteenth time.

Since the agreement was signed, the government detained an organizer of the opposition primary, while others had their passports suspended while they were under investigation. Maduro also tried to provoke a conflict with the Guyanese government over the hotly-disputed region of the Esequibo, which covers 2/3 of the Guyanese territory, and has significant oil reserves. Now, the regime gave the Barbados agreement a Christian burial by confirming that Machado is still banned from running for office.

The US government responded by giving Venezuela an ultimatum. Maduro’s government will have until April to change its policy and allow Machado to run. If this does not happen, they will reimpose sanctions. Meanwhile, the US immediately reimposed sanctions against the Venezuelan mining sector, banning US companies from dealing with Venezuelan state mining company, Minerven.

Jorge Rodríguez, president of the National Assembly, said that the Venezuelan government would return to the negotiating table in Barbados per Norway’s request. Norway is one of the facilitators of the dialogue between the Venezuelan regime and the opposition. At first glance, this might seem like a sign of weakness from the Venezuelan regime—at the first threat from the US of reimposing sanctions, they’re returning to the negotiation table. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, this development reveals some fundamental flaws in the US strategy towards Venezuela.

First, Biden’s Administration has unclear goals. And, second, the moves they have made seem to be based on a misunderstanding of the nature of the Venezuelan regime.

Biden’s Goals for Venezuela

The first issue is clear. No one really knows what the Biden Administration wants to attain with its policy in Venezuela. Do they want a regime change? Do they want free and fair elections? Do they want an oil partner? Do they want a new ally?

The first option was something the Trump administration flirted with. Here and there, the possibility of a military intervention or support for a coup was mentioned, but the Biden administration seems to have discarded this possibility.

The second seems to be their public position. But it is unclear if they are actually interested in getting free and fair elections in Venezuela. The easing of sanctions and the rhetoric justifying it has been too naïve, and pressure too soft and slow. Thus, “free and fair elections” is just a narrative—or else the people in charge of Venezuela in the State Department are first-year students of international relations. Or both.

Venezuela is a dictatorship, and the Maduro regime has no interest whatsoever in free and fair elections. This should be obvious.

Maduro refused to allow free and fair elections even when his leadership led the country to hyperinflation, a humanitarian crisis, sanctions, power cuts, the US threatening an intervention, and protests throughout the country. He won’t allow them now, when the economic situation is timidly improving and there are no massive protests.

The third is, perhaps, the private position of many in the State Department. Easing some sanctions in the exchange of oil might certainly benefit some American companies, considering that Russian oil is toxic internationally and Caracas is way closer than Siberia. Improving relations could also make way for deportation flights to Venezuela, considering the increasing number of Venezuelans illegally crossing the southern border.

But there are complications to this position. First, Venezuelan oil is classified as heavy or extra heavy, meaning it is harder to process and typically has to be mixed with lighter oil to be refined. Only some very specific refineries can do the work.

Second, if the US simply wants Venezuelan oil, it makes no sense to keep issuing threats to reimpose sanctions, which obviously can’t be taken seriously. Meanwhile, Maduro has already threatened to stop accepting deportation flights from the US, which was part of the Barbados agreement.

The fourth position, that Biden is trying to court Maduro against China and Russia, seems to be even wilder and more naïve than believing he will allow free and fair elections. The ties with China and Russia are too large to ignore. They are economic, geopolitical, and ideological. That won’t change because the US is buying some oil and eliminating sanctions. The Venezuelan regime needs an enemy, and the US is perfect for that part.

The likeliest possibility is that the Biden administration seems to be caught up between these three positions. So, it is unclear what they actually want to achieve.

Time for a Reality Check

The Biden administration is negotiating with Venezuela as if it were a good-faith actor. They think they can quid pro quo their way out of the issue. They can’t. Venezuela is a dictatorship, and the Maduro regime has no interest whatsoever in free and fair elections. This should be obvious.

The US can’t simply eliminate sanctions and get free elections in return. If that were a real possibility, the problem would have been solved many years ago. In fact, Venezuela’s will to return to the negotiation table does not signal weakness. It simply shows that they want to gain more time.

Venezuela did not give anything in Barbados. The only tangible sign of a willingness to cooperate was the release of some political prisoners, and lifting the ban to run for office of a few minor politicians. In return, the US released an essential figure in Saab and lifted sanctions. It’s true they threatened to reimpose sanctions. They did the same a year ago. The sanctions never came back. Presumably, Venezuelan officials think it likely that if they return to the negotiations and play nice, the sanctions might never return.

In fact, they may even allow Machado to run, only to ban her again in the future or commit fraud at the election. It would be nothing new.

While Rodríguez said the government was ready to return to negotiations in Barbados, he also said they would approve an election calendar soon. Presidential elections are to be held in 2024 but the calendar has not been defined. It seems that the Maduro government is looking to announce the calendar soon. The calendar includes, for example, the dates to register candidates, the start and end of the campaign, and the day of the election itself.

By pushing for an early date, Maduro is trying to create trouble in the opposition. Despite winning the primary overwhelmingly, the biggest opposition parties don’t like Machado. They believe she’s too radical, inflexible, and smug. They don’t like that they were humiliated in the primary.

By pushing for an early deadline to register a candidate, even while Machado was still banned from running, the government created a dilemma: Should the opposition stand by Machado’s candidacy? Should Machado appoint a substitute candidate? Should the opposition choose a new candidate by consensus?

The Venezuelan government doesn’t play by the rules. The April ultimatum might end up being moot if the deadline to register a candidate is set for March.

It is true of course that Maduro would like the US to ease sanctions but he has also learned to live with them. Moreover, he knows that small shows of strength can put enough pressure on the US to do what he wants. He can always jail some American executives or opposition politicians, move troops to the Esequibo border, and make Biden ease sanctions. It’s what he’s done in the past.

Meanwhile, Biden has not achieved anything with Venezuela. Venezuela is not closer to democracy. It’s not closer to being a commercial partner, much less an ally. It’s even closer to China and Russia than it was before.

It’s a foreign policy disaster, no matter how you see it.