The editors present the five most-read Law & Liberty forum discussions of 2020.

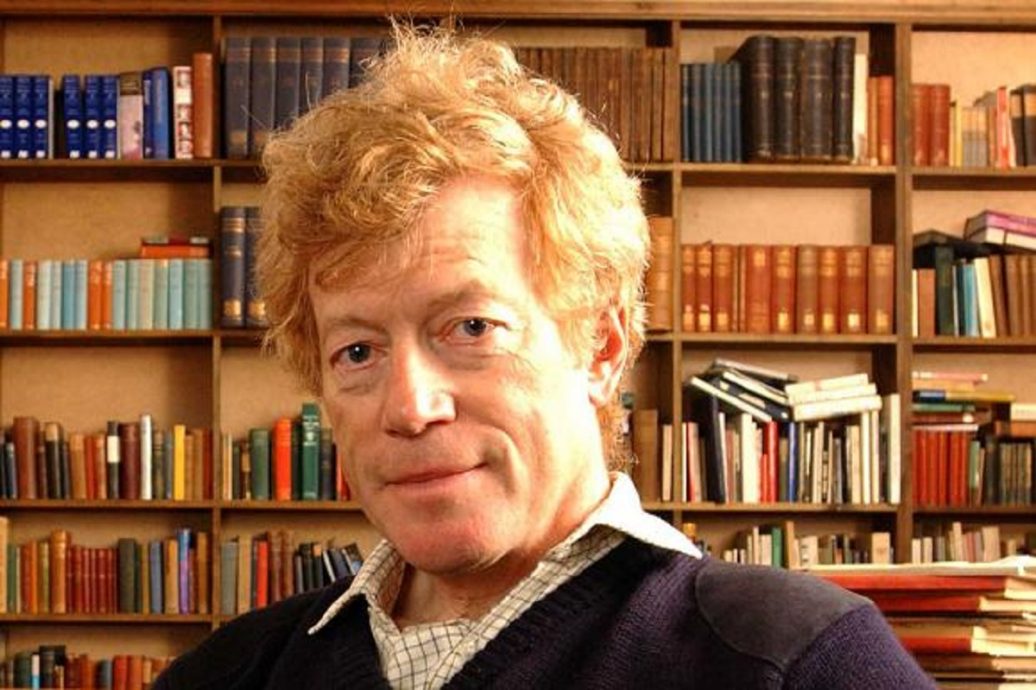

Learning from Roger Scruton

I encountered Roger Scruton (long before he was knighted) for the first time at Oxford, where he delivered guest seminars for BCL, MPhil, and DPhil students reading jurisprudence. He was there at the invitation of Professor Tony Honoré, a Roman law specialist, and Professor John Gardner, a scholar of legal philosophy. The two Dons ran the course jointly; Sir Roger was a “ring-in.”

People are often surprised when I tell them Scruton taught me as part of a law degree, but he was a qualified barrister — what Americans call a “trial attorney” — among his many other accomplishments. Notably, he never practiced: he couldn’t afford to take a year off work to complete a pupillage. In 1978, paid pupillages (something I had the good fortune to experience) were still in the future. This small detail of Scruton’s employment history is a reminder that although his name was associated with High Toryism, his origins were humble and his early progress as an intellectual came about through scholarships.

The seminars in question were delivered at All Souls, Oxford. They were very good seminars, too. Our classes were held in part of the college called the “Old Library.” I suspect we broke every health-and-safety rule known to man. Students finished up sitting in window ledges and on the floor. Possessed of a resonant, sonorous voice and an extraordinary head of what I came to call “Mad Professor Hair,” Scruton had an uncanny ability to speak in complete sentences, something I had not seen before and have only rarely seen since. Everything he said was extraordinarily thoughtful even when one disagreed with it with every fibre of one’s being.

See, I’m as gay as a handbag full of rainbows and was once juvenile enough to wear a Pride pin to one of Scruton’s seminars. If he gave a toss there was no sign. He continued to teach in that remarkable voice and succeeded in piercing the carapace of my half-smart provocation by sheer force of intellect. Even then (I now have a goodly collection of white hairs), most students were left-leaning or, occasionally, classical liberal. There were few genuine conservatives. Those of us who considered ourselves classical liberals would go along to Oxford University Conservative Association “Port & Policy” events because they were more generous with alcohol, cheese, and chocolates than Labour, not out of any loyalty to Scruton-style conservatism.

Scruton, however, forced one to think. He persuaded me that urban planning since the Second World War did more damage to the country’s architectural fabric than the Luftwaffe. He really had forgotten more about what’s now called “the built environment” than most people will ever know. The fact that among the offendotrons routinely accusing him of Islamophobia and anti-Semitism and homophobia and God knows what else were a lot of moaning architects was a sure sign he had landed on an intellectual pinch-point that simply hadn’t been worked through. He did this rather a lot.

Years ago, he argued that “once identified as right-wing you are beyond the pale of argument; your views are irrelevant, your character discredited, your presence in the world a mistake. You are not an opponent to be argued with, but a disease to be shunned.” At the time it struck me as hyperbole. However, what happened to him in the year-and-a-half before his death — when there was a concerted attempt to destroy him as a human being in addition to getting him sacked from his job — made it come true. What American sociologist Freddie deBoer calls “offence archaeologists” — people determined to “sniff out baddies doing bad things” by going through everything he’d ever said or written — seemed destined to bring about an intellectual climate where it would be impossible to be publicly conservative about anything. And not just in Scruton’s signature fields of aesthetics and architecture, but on immigration, sexual morality, foreign policy, or public displays of patriotism.

This development has not been without negative consequences: the frenzied response to anyone even remotely controversial means that — among the Great British Public — when an individual pitches up and accuses someone else of racism or anti-Semitism or sexism or homophobia or [x], the default reaction outside the Westminster Village is now disbelief. It took years for anti-Semitism in the Labour Party to be taken seriously (despite desultory Conservative Party attempts to use it for shallow electoral advantage) for precisely this reason.

To my mind, the only thing that cut through during the election campaign itself was the intercession of Britain’s Chief Rabbi, who stated bluntly that Jeremy Corbyn “was unfit for high office.” Unlike Christian and Muslim clerics — who tend to be rent-a-gobs — Jewish clerics seldom make public interventions. That the poor man was clearly deeply uncomfortable at the dreadful position in which he found himself only made the problem more tangible. Relatedly, few people remember that the Archbishop of Canterbury backed Rabbi Mirvis at the time, simply because we’ve come to expect leaders from the other two monotheisms to hold forth on, well, everything.

Then, of course — precisely a month before Sir Roger died — the Conservatives won a thumping electoral majority as voters put both Labour and its horrid mislabelling of all and sundry to the sword. All at once, the stultifying atmosphere lifted. And both before and since Scruton’s death, the new regime has made it clear it is going to “push back” on culture.

Among other things, the BBC is being threatened with decriminalising non-payment of the licence fee, which would not only remove the leading cause of female imprisonment in these Islands but also force it to speak with the country, not at it. Dominic Cummings, Boris’s Svengali in Number 10, has been permitted to execute what Americans would call “an end run” around the civil service, recruiting new staff based not on mindless “diversity metrics” but on numeracy and intellectual inventiveness. The House of Lords — so obstructionist during the Brexit process last year — is being menaced with removal to York. This latter, in my view, is not such a good idea (the UK’s Constitution is already in a delicate state) but the intent is nonetheless clear.

Here, then — in a spirit of both reflection and in response to dipping in and out of my Scruton library over the past fortnight — are views I hold because he was once my teacher. They are not his views, but mine (although they may sometimes be adjacent). They are more or less conservative, and the 12 December election result has made it possible to say them in public without peremptory cancellation.

I

A lot of people from minorities (I’ve detected it in my own character) want to be liked and accepted. Unfortunately, a hectoring demand for sackings and public obloquy is often an attempt to mandate respect and affection when the best one can hope for is non-interference. Anyone who has been in a schoolyard and seen a teacher tell two warring children to “shake hands and be friends” knows how fake it is. You can’t make people like each other. You can only stop them hitting each other. If there is something about you that places you outside the norm — whether it is diet, sexuality, personal habits, or religion, the best you can hope for is tolerance. If you attempt to mandate acceptance, you will find yourself roundly disliked.

II

There are Burkean and Scrutonesque cases both for and against Brexit, something worth remembering now we know it will definitely occur. The argument in favour is essentially a riff on Churchill’s “if Britain must choose between Europe and the open sea, she must always choose the open sea.” The argument against is the simple one (articulated by many people, including me), that it is difficult to leave a club when you have been a member for nearly 50 years, especially when membership means one has voluntarily taken on many club rules. As trade negotiations progress, we need to keep this in mind.

III

For many years, I was opposed to Middle Eastern wars in a diffuse way, because they always seemed to make the situation worse and cost an absolute fortune. My current argument against military adventurism, however, does not concern itself with the hopes and aspirations of people “over there,” but war over there leading to unwanted refugees “over here.” I do not think either people or cultures are equal, and it has to be possible to note that refugees — no matter how benighted their circumstances — are sometimes the authors of their own misfortune. Nation-states should therefore be allowed — where there is an electoral mandate — to abrogate the Refugee Convention, or at least legislate around it, as Australia has done.

IV

The desire for ideological consistency is noble but misplaced. I used to suffer from it, until it shattered on contact with political reality (two years working for a Senate crossbencher in Australia). Before 2014, people used to ask my views on things to see if they could forecast them, I was so predictable. My job meant I developed (under intense real-world political pressure) a resonant respect for the collective wisdom of the electorate at the ballot box, and also came to realise that rights are not pre-existing but held against our fellow-creatures, and so require a measure of their consent. This means accepting that it is almost always improper to put policy out of the electorate’s reach, while understanding that ideological consistency applied to practical politics struggles to course-correct, often with dreadful consequences.

Vale, Sir Roger Scruton. I shall miss you terribly.