In his famous cello concerto, Sir Edward Elgar voices compassion for human suffering.

Majesty, Mystery, and Malaise in Maestro

Downbeats are what initiate musical measures; upbeats are what end them. For the conductor and orchestra, the downbeat creates the sense of structure and provides stability, grounding the composition with a rhythmic anchor. The upbeat is what introduces anticipation and motion. Rhythm—the necessary pulse of any piece of music—has as its basis the symbiotic relationship between these, and yet it’s the downbeat that acts as the heartbeat within.

Intriguingly, a piece of music doesn’t have to start with a downbeat. There can be a few pickup notes of introduction (anacrusis, for the formal types keeping score) from a preceding measure to help create the atmospheric scene. For that matter, the initial downbeat of a musical composition doesn’t even have to be a note at all: it can be that space of musical silence signified by a rest. What does it mean to anchor an artistic piece whose medium is sound—in a beat of silence?

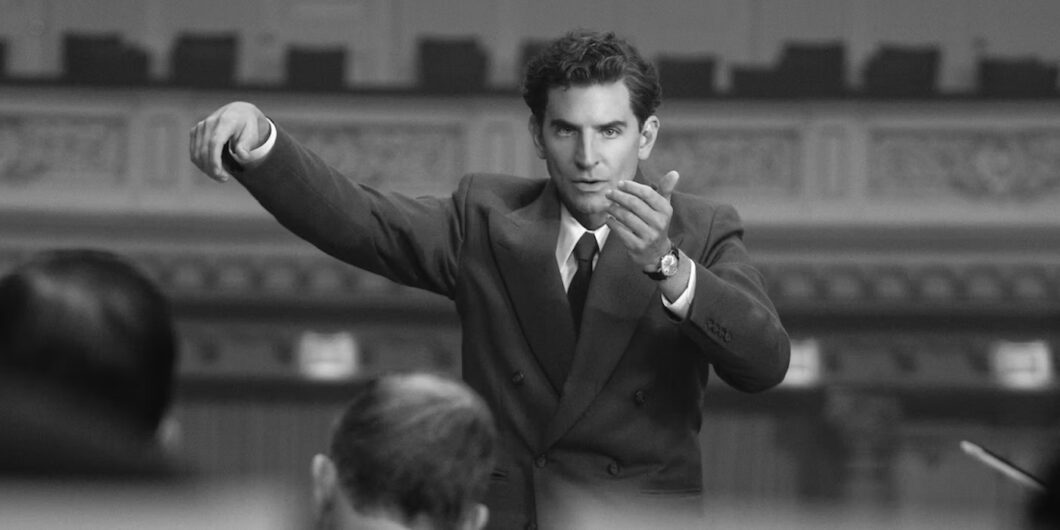

Bradley Cooper’s Leonard “Lenny” Bernstein bursts onto the primetime stage in his film Maestro conducting—at the last minute and unrehearsed—Robert Schumann’s Manfred Overture. But Manfred’s opening downbeat is a rest. If the orchestra doesn’t “get” that with the conductor, inescapable chaos will ensue. Maestro the film, however, begins with its own particular anacrusis. It’s scaffolded around a piano rendition of a sequence from Bernstein’s opera A Quiet Place. The meditative scene sounds a note of personified silence—about one particular absence. This frames the film, which ends as it begins, with the aged and widowed Bernstein at the piano, invoking an image of his deceased wife Felicia Montealegre. Can a cinematic anacrusis that involves both sound and sight function as a downbeat “rest”—a space of specialized but anchoring silence as it were?

If so, there are more wonderings to navigate here than those of mere biography.

Maestro, directed by Cooper and produced in part by veteran filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Stephen Spielberg, is Cooper’s second directorial outing. It is his second film about music and those musicians who are impelled to create music, not simply perform it. There are certainly many similarities to his first film, A Star is Born. Maestro is equally suffused with music—Bernstein’s own; Schumann, William Walton, Beethoven, Lincoln Chase, and pivotally, Gustav Mahler. It is similarly about artistic souls and the world they inhabit. And Maestro is also about the types of human relationships that can form around the nucleus of the artist-genius, and whether their human relationships are inevitably or necessarily less humane. Maestro, however, is a subtler affair about the mysteries of human creativity and the human soul.

Maestro is not your standard musical biopic. This doesn’t deny that familiar tropes are the building blocks of the story throughout—there’s the opening quote by the film’s real-life protagonist; the reflective scene by the older man cutting to the big pivotal night of his young career; the meeting of various loves; montages of artistic highlights interspersed with life events; the midcareer anxieties and family anguishes; reconciliations and a death; the return to that reflective opening scene. But Cooper and cinematographer Matthew Libatique frame and shoot these tropes in a woven rather than linear fashion. This makes their very composition a part of the specific story Cooper is telling.

The puzzlement of how a person whose entire artistic and professional persona flows from his extraordinary perceptive and communicative abilities, could fail to understand the sensitivities of actual human relationships, is not one that Maestro attempts to solve.

Viewers may start to suspect that the story is not really about the historical Leonard Bernstein at all. There are no chyrons or newspapers flashing headlines telling us the year or concurrent world events. Nothing is mentioned about the length (and true breadth) of Bernstein’s career, the date of his death, or the fate of his closest peers and proteges. There are no career stats, nor reminders of how Bernstein measured up to the anticipation that he would be “America’s first great conductor.” Very little is said about what it means to be a conductor—a musical Moses tasked with anticipating the way for his musicians. But art and creativity and human communication clearly are the substance of the film.

The cue lies in the film’s opening quote: “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.”

Perhaps for Cooper, the character Lenny Bernstein is the piece of art—or its analogy. In that case, his meaning must be in the tension between the musical artist’s dependency upon people to compose for and perform before, and the composer’s need for non-performative solitude and interior reflection in which to create (having “a grand inner life,” as Lenny puts it). Lenny is both conductor and composer; he desires to be both; he wavers between the two. Either persona leeches off of the ability to be fully the other. Composer, as a musical creator, seems to be the higher calling, and yet Lenny cannot bear to be alone: he has a near-pathological need not to be separated from people, such that he even leaves the door open when using the bathroom. More interestingly, that tension between the exhibitive and the creative aspects of music-making are mirrored in Cooper’s cinematic project: Film is disclosive, after all, and yet the core of what’s being disclosed in Maestro is a mystery that’s so deeply personal—and yet cosmic—that it’s not to be solved, only guarded.

Cooper emphasizes the veil concealing the human creative process rather than rending it with some performative “raw” vulnerability. This is precisely the opposite of what contemporary audiences have come to expect of a film about artistic figures. It’s daring of Cooper, given the nature of his art form. But as Cooper stands as guardian to the historical Bernstein’s wish to preserve the creative mystery, so does the character of Bernstein’s wife, Felicia Montealegre, stand as guardian to Lenny’s persona. She is the guardian of his creativity, not the source of it; hence, at certain points, her deep anger at Lenny’s “unfaithfulness” to his composing. Felicia is herself a musician, after all, and an artist, too.

Carey Mulligan’s wonderfully, sensitively espressivo Felicia does not fulfill the expected trope of muse to her unrestrainable husband. She makes Felicia Lenny’s forever anchor, the necessary structure countering the chosen chaos of his life—the downbeat to his upbeat. Despite his fondness and affection, Lenny largely fails to appreciate what Felicia is and does when she is in front of him and is even oblivious to the true why of her deep importance to his life; this forms the quiet tragedy of the tale. Though she is the heart of the story, Felicia is quite literally always in Lenny’s shadow—until her death, that is, when Lenny is in hers.

“I love two things, music and people. I don’t know which I like better, but I make music because I love people. I love to play for them and communicate with them on the deepest, which is the musical, level.” In the film, Lenny relays a version of this historical quote from a 1990 Bernstein interview, but as a middle-aged man chain-smoking cigarettes in the backyard of his own estate. It’s all of a piece of his professional success, and yet he’s restless and preoccupied, reflecting to art critic and biographer John Gruen that to its peril, the world has been losing its ability for creativity. “I feel the world is on the verge of collapse. … The diminution of creativity … which has come to a grinding halt. I mean, not scientifically. That has exploded. … But I know that Felicia—she senses it enormously.”

These two later quotes are the addenda to that first introductory one. Together they more properly reveal the framework for the real story Cooper has identified within or via the relationship of Bernstein and his wife alongside Bernstein’s string of male lovers. That story is the revelation of the cruel irony and casual cruelty, of the musical genius in love with artistic communication whose fixation on self-expression deafens him to what his most intimate audience needs to hear. Music without words may be the highest or deepest human expression, philosophically speaking, but enfleshed husbands and wives, parents and children, cannot subsist on such music alone. The physical reality of separate bodies forever prevents the “marriage of true minds.” Sometimes, words are what’s required.

To be a maestro, a conductor of Bernstein’s caliber, requires an extraordinary sensitivity to the minutest of factors—of tone, pitch, timing, phrasing, dynamics, potentialities of various instruments, individual players, sections of an orchestra, the whole human symphony cum audience along with the particular musical composition on the podium. It’s a stage drama, but an aural one, and the conductor is the stage director. How the conductor gets his musicians to play sequences of notes in a particular way, leading toward the next sequences of notes, and onward to an ending, fundamentally matters. And it requires reservoirs of thoughtfulness, and not just feeling, on the conductor’s part.

Perhaps Felicia’s adoring love for and guardianship of Lenny’s creativity mistook mere great talent for true genius. The latter was impossible given Lenny’s own unwillingness or inability to separate himself enough from his admirers to cultivate a grand enough interior silence.

In a penultimate sequence of Maestro, we’re privy to a minuscule clinic in the difference that mastering all of these aspects has on the music as actually performed and heard. A now widowed Lenny gives a coaching masterclass at Tanglewood. Student conductor William struggles through a particular sequence of the Allegro Vivace from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 8. The aspiring conductor doesn’t know how to “get out” from “retarding into the fermata” and into the next musical phrase—“Are you gonna bleed out of it; drip out of it … leak out of it, that’s what it sounds like.” Lenny challenges William with his inarticulateness. Eventually, he takes William’s baton and demonstrates how to do it. Lenny signals a cutoff and an upbeat, “… quarters. I think that’s what you really mean.” You can hear instantaneously the difference, how meandering notes suddenly become purposeful; how a defined moment was articulated with a few precise flicks of the conductor’s wrists.

But Lenny’s genius-level perceptions and sensitivity in musical matters do not seem to translate to his human relationships. When the breakup in their marriage comes, it is the result of Lenny “getting sloppy” in his extramarital homosexual affairs. But what Felicia means by “sloppy” is Lenny’s refusal to be sensitive enough about the modicum of public respect and dignity she had hoped and asked for in exchange for accepting his sexual behaviors. He is publicly flaunting his unconventional affairs. But her anger is deeper than some disappointed desire for conformity to social convention. The basic kindness of recognizing what deeply matters to a spouse and acting accordingly ultimately does not figure into Lenny’s calculation. It had always been Lenny’s world, with everyone else simply privileged to be in it.

Felicia ultimately recognizes that neither her own artist’s appreciation of Lenny’s gifts, nor her guardianship of his creative genius, nor her intellectual acceptance of the situation could ever cancel the very real heart-sting of that truth. In the poignant, deftly portrayed sequence of Felicia’s cancer diagnosis and death (almost too poignant for anyone who’s witnessed a loved one succumb to cancer), Felicia herself finally gives words to this most basic need not just of the marital and the familial relationship, but of the human heart: “You know, all you need, all anyone needs is to be sensitive to others,” she tells her daughter. “Kindness. Kindness. Kindness.” Kindness is the proof of their seeing the other person’s vulnerabilities, of acknowledging them for who they are as a distinct human being. But genius, while it may be a gift, is clearly not always a blessing in this regard.

The puzzlement of how a person whose entire artistic and professional persona flows from his extraordinary perceptive and communicative abilities, could fail to understand the sensitivities of actual human relationships, is not one that Maestro attempts to solve. But Cooper has said that this imbalanced relationship of a God-like Bernstein “coming down to us and for his destiny,” as though the modern musical god were being pulled by the hoi polloi into their darkened world, in order for it to be enlivened with his gifts, was precisely the thing that Cooper had wanted to explore. This certainly illuminates the main first sequence, which has a nearly-naked Lenny receiving the fateful phone call about the last-minute Carnegie debut in his apartment above Carnegie Hall. He rips open the curtains with a jubilant “You got it boy!”—only to play the drums on the exposed buttocks of his sleeping lover while bounding out the door for a tracked descent to the fabled stage. It’s the world as an instrument, cinematized.

That descent and what it means for us mere mortals—and for Lenny himself—seems cleverly echoed in the pacing, shots, and styles of Cooper’s film as it follows Lenny through some forty-odd years of his life. Our poor lives, at least, are enlivened by his: It’s exhilarating and heady and glorious at first, and Lenny and Felicia’s meeting and flirting and coupling is its own grand 1940s movie, complete with high-contrast black-and-white and Academy ratio frames. We move through fantasy sets and scenes of Bernstein’s own artistic creations, Fancy Free and On the Town, and on to real-life radio and TV interviews of the young couple’s married and professional lives. And as the decades succeed each other in Lenny and Felicia’s lives, so too do the film stock, the color palettes, and the aspect ratio change to match their historical era. The banter and bubbliness and soulful conversations become short and strained exchanges, marked more by what is not being said than what is. There’s contention and aloofness, distrust, and a certain malaise that has settled in by the time we reach the early 1970s, despite Lenny’s continued professional success. Creativity is in decline, right in front of us.

And yet it’s not that any artistic or creative energy has declined simply: the pinnacle of Maestro is arguably the six-minute live shot of the recreation of Bernstein’s famous 1973 performance of Mahler’s Symphony No.2, “Resurrection,” with the London Symphony Orchestra in Ely Cathedral. It is stunningly shot. Quite simply, it’s transportive.

Cooper did his homework well (spending six years studying conducting with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, music and artistic director of the Philadelphia Orchestra), conveying the essence of a Bernstein conducting event in all its sweaty, physical ecstaticness. (Bernstein was famous for conducting even just with his eyebrows.) Some have criticized Cooper’s performance as hammy overacting, but it’s worth remembering that audiences rarely see much more than the backside of the conductor, while the camera shows us what the orchestra sees—his face. But the Mahler moment is doubly significant for what the symphony itself represents—besides being a gigantic, superhuman, 90-minute musical effort that demands extraordinarily high technical skills alongside emotional depths from musicians—the symphony was also a working out of the composer’s idea of creating a world of its own.

Lenny, too, remains in his own self-referential yet performative world. But there is no “resurrection” for Lenny, just a specter of the deceased Felicia that’s now vividly present in his mind’s eye. He is with Felicia in her dying moments; but then he is back to being a too-old adult attempting to act like a college kid alongside some of his partying Tanglewood students; blasting R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” from his convertible; being filmed talking about himself, and how “summer sings less often” now. There’s nothing godlike in his presentation or behavior anymore, though there is something performative, and it’s now clear that those are not the same. Nor is this a “sad” scene about decline. But it is an embarrassing one.

The “diminution of creativity” of which Lenny had earlier complained turns out to be in his own case a diminution of dignity, which the cinematographers subtly capture. Perhaps the musical creator-god did not in the end so much descend from his heights to give technicolor to the people. Rather, technicolor revealed him to be rather pedestrianly human after all, because so perplexingly lacking in humane sensitivity in life outside of art. This thought leads to a less kind, but no less warranted thought: that perhaps Felicia’s adoring love for and guardianship of Lenny’s creativity mistook mere great talent for true genius. The latter was impossible given Lenny’s own unwillingness or inability to separate himself enough from his admirers to cultivate a grand enough interior silence. But for the film Maestro to have said this explicitly, its directors would have had to reduce any mystery of human creativity to a mere output of its creator’s behavior. This, thankfully, they did not do, allowing for the more pregnant silence.

Whether and how to separate the art from the artist is one of the most frequently revisited themes raised by another recent film about conducting and music, Todd Field’s Tár, the 2022 film about the world’s “most renowned” fictional interpreter of Mahler and a protege of Leonard Bernstein, Lydia Tár (played by Cate Blanchett). But from the perspective of Maestro, the richest themes of Tár are in its showing of exactly how high the cost is to conductors and musical artists of transmitting to their audiences the transcendent compositions of a universal human heritage, faithfully and well. Every conductor, but especially the greatest conductors, bear interiorly the immense responsibility of transmitting anew some of the most sophisticated artistic achievements of the human race. And the instrument they have to rely on to do this is not some passive wooden or brass one, but a human instrument, the orchestra. They must therefore control that instrument, and a veritable symphony of tangential factors, the most important of which is time itself—and silence.

“Keeping time—it’s no small thing,” Blanchett’s Tár says to the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik. “Time is the thing. It’s the essential piece of interpretation. You cannot start without me. I start the clock. My left hand shapes, but my right hand marks time, and moves it forward,” she continues. “The reality is, that right from the very beginning I know precisely what time it is, and the exact moment that you and I will arrive at our destination, together.” Of course, it turns out that like Lenny, the infinitely more artistically and intellectually disciplined Tár also does not know the moment or place of arrival of her destination, severely if not hideously miscalculating the rhythm of her own life choices and how different the tempi are between her interpretation of her art, job, profession, and artistic responsibilities as a transmitter of music, and that of the vocal critics of the world.

Tasked with being so godlike as to even control time within the confines of the concert hall, the enduring mystery is how, when it comes to the most human interactions of all, the best conductors so often miss the beat.