Jefferson's "Essay in Architecture"

Rebecca Burgess is joined by Frank Cogliano to discuss Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, and the Jeffersonian legacy.

Brian Smith:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. This podcast is a production of the online journal, Law & Liberty, and hosted by our staff. Please visit us at lawliberty.org, and thank you for listening.

Rebecca Burgess:

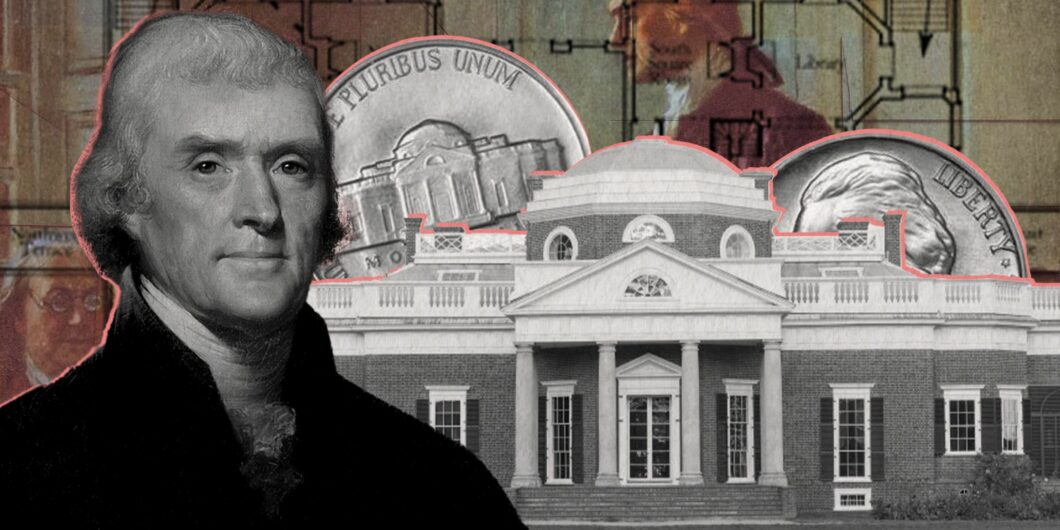

We know this outline from every nickel we’ve ever handled, it’s part and parcel of America’s iconography, the pillared domed home Thomas Jefferson built on his mountaintop outside Charlottesville, Virginia, and named Monticello. Jefferson called his self-designed creation his “essay in architecture,” but it is not just a thought-provoking essay in building materials and lines and perspectives, it’s an essay in American political and social thought, not to mention America’s political history. Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. My name is Rebecca Burgess. I’m a contributing editor at Law & Liberty, a senior fellow at the Yorktown Institute, and a visiting fellow with the Independent Women’s Forum.

For the next 30 to 40 or so minutes, discussing Jefferson’s Monticello on the 100th anniversary of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, is Frank Cogliano, Interim Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. Cogliano is a professor of American history at the University of Edinburgh, where he serves as the University Dean International from North America. He’s a specialist in the history of the American Revolution and the early United States and is the author or editor of nine books, including Thomas Jefferson: Reputation and Legacy and Emperor of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson’s Foreign Policy. Welcome, Professor Cogliano.

Frank Cogliano:

Thank you, Rebecca. I’m thrilled to be here.

Rebecca Burgess:

Wonderful. And I should have asked you if you’re coming from Scotland today or from Monticello, Charlottesville.

Frank Cogliano:

I’m coming to you from Charlottesville today, I’m pleased to say. I’m spending the current year here in Charlottesville at Monticello, directing the International Center for Jefferson Studies.

Rebecca Burgess:

Could you tell us just a quick little background about what the International Center for Jefferson Studies is? So many people know the building, Monticello, the home, but don’t know that there is this whole study center.

Frank Cogliano:

Yes, I’d be happy to. So Monticello is the home, as you say, that many people will be familiar with and hopefully they’ve visited. But Monticello is much more than the house; and it’s owned by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and run as a museum by the foundation. But the foundation has several other arms to it, if you will, one of which is the International Center for Jefferson Studies, which is located in another historic home, about a half mile or so beyond the main entrance to Monticello at a place called Kenwood. And the International Center for Jefferson Studies will celebrate its 30th anniversary next year in 2024. And it was set up to be a center for scholarship and research and to encourage scholarship and research into Jefferson and the world that Jefferson inhabited, not just on Jefferson himself, although we do a lot of research in that area, but also on the American Revolution, the era of the American Revolution, the history of plantation slavery. As I say, the world that Jefferson inhabited and helped to shape.

For 30 years, the center, through promoting scholarship, both internally within Monticello but also externally through fellowships for scholars from all over the world, promoting conferences, promoting publication, and helping new scholars publish but also senior scholars, has really helped to shape our understanding of Jefferson and his time. And in so doing, has led… I mean in the past 30 years, and I hope we’ll get to this, there’s been a real kind of efflorescence of studies about Jefferson in his time, and I think ICJS and, in particular, Monticello generally has played a part in that.

Rebecca Burgess:

Don’t worry, we will definitely get to the 30 years of efflorescence, as you call it. A wonderful word, wonderful image. So we’ll probably go a little bit chronologically here, but I did kind of want to for our listeners start out by just saying the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has two twin pillars of its mission: preservation and education. And I’m hoping that our conversation touches on both, but really on the education element because it has become so vital towards America’s understanding of Jefferson actually through the decades, through now a century as we are at the 100th anniversary this year. And it includes, as you mentioned, the other historic home, Kenwood. There’s a fascinating presidential history that extends beyond Jefferson through Lincoln to the Civil War, obviously, to FDR in World War II, and that’s a wonderful story as well.

But if we want to start maybe at the beginning of the kind of conceptual question here, the history of presidential homes and estates, including most especially those of American Founders, often are stories that are just as rich and complex and interesting as that of their original owners, and they often reflect the larger history of the American nation. This is especially true with Monticello. Many are not aware, of course, that unlike in Europe and America, the homes of the Founders or presidents are not owned by the federal government nor fully funded by taxpayer support. They don’t necessarily have continuing grants even from the NEA, the National Endowment of the Arts, or the National Endowment of Humanities. So it’s really been up to private individuals and foundations to protect and preserve them.

So Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello has a very rocky few years or decades or beyond decades after his death… His heirs had to sell his estate after his death to settle his debts with the infamous story of the public auction of enslaved individuals on the front lawn. And Monticello passes out of the hands of the Jefferson family. Can you give us just a little bit of that story of what happened after the death of Jefferson, happens before this American Jewish family, the Levy family, comes into the picture?

Frank Cogliano:

Sure, absolutely. And you’ve done a very good job of summing up the kind of big picture, so thank you for that, Rebecca. As you say, Jefferson died on, many people will know, on the 4th of July, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, as did John Adams. And Jefferson died in debt. He was in pretty extreme debt for a number of reasons, which we can discuss if you like. But that debt resulted in his heirs having to sell his estate, which was Monticello, but also, as you referenced, his human capital as well, the people he enslaved. And so more than a hundred people were auctioned on the west portico. So you mentioned the nickel. It’s the nickel view of the house, the house that one sees on the nickel today and has for decades. That view on those steps, more than a hundred people were auctioned in January of 1827, and the home fell into a state of disrepair.

It passed through the hands of several local people in the decade immediately after Jefferson’s death. And then, it was purchased in 1836 by a man named Uriah Levy, who was an officer in the United States Navy from New York. And Levy was unusual. He was one of the few Jewish officers in the Navy at that time, and he was a reformer. He was a sort of social reformer. He campaigned against flogging in the Navy, for example, as a punishment. And he bought Monticello because he admired Jefferson’s commitment to freedom of religion.

This is where I think Levy’s own religion, the fact that he was Jewish in a majority Christian country at that time, was really important. So he bought it as a home, and really he used it as a summer home, but he also bought it and sought to preserve it as a monument and as a tribute to Jefferson’s commitment to religious liberty, which was one of the things enshrined on Jefferson’s gravestone here on the mountain top. And the Levy family owned Monticello for longer than the Jeffersons did. They owned it for almost a century, for about 90 years, throughout most of the 19th century. It’s a complicated history because Commodore Levy, Uriah Levy, as he’s called, died in 1862, and he sought to leave the house for the United States at that point.

As many listeners will be aware, and undoubtedly you’re aware, there was a small matter of the Civil War going on in 1862, and Monticello was in Virginia. So, there was some debate about whether it was in the United States or not at that point. So, leaving it to the United States was a complicated question. And eventually, there was a series of lawsuits, and again, we don’t need to belabor this history, but the man who comes to own Monticello is one of Uriah Levy’s nephews, a man with the wonderful name of Jefferson Monroe Levy and Jefferson Monroe Levy owns the house basically after the Civil War down to the early 20th century, he served as a congressman at one point, but when he eventually sold it to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, then the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, which is the foundation established in 1923.

Rebecca Burgess:

If we could just maybe have a little tangent there about that whole Civil War moment and Levy trying to gift it to the United States and the United States refusing Monticello and why he wanted to offer it to the United States, to be a home for orphans of naval officers. I think this is very interesting. And, of course, just the bloody reality that the fields around Monticello, that area of Virginia, is the side of the bloodiest battlefields.

Frank Cogliano:

There was a lot of fighting, as you know, in central and northern Virginia during the Civil War. So you are right. Commodore Levy’s wish to create a kind of an orphanage basically at Monticello for the children of naval officers was again in fitting with his kind of reformist impulses, but it was completely impractical. And he knew that at the time, during the Civil War. That plan or that ambition or that aspiration, I should say, didn’t bear fruit. What’s interesting I think, and you made reference to this in your introductory comments a moment ago, is the fact that most presidential homes are not owned by the United States government. And although presidential libraries, which are often but not always at presidential homes, are homes run by the national archives, again, there’s often a kind of quasi-public-private dimension to this. But with the homes themselves, especially in the 19th century, the preservation of these homes was not seen as something that the government should do.

And the best example in the mid-19th century, so shortly before Uriah Levy died in 1862, is Mount Vernon, and of course, Mount Vernon is bought and preserved for the nation by the organization that owns and runs it to this day as a museum, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association. The Mount Vernon Ladies Association doesn’t take any money from the federal government and runs Mount Vernon as a preserved and maintains Mount Vernon as a museum. And that was the model that emerged in the 19th century. And that’s very much the model that the founders of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation have in mind when they buy the house from Jefferson Monroe Levy in 1923.

Rebecca Burgess:

And there was also an unfortunate note, if I’m remembering right, of antisemitism about the Levy family owning a Monticello, which in part prompted… Or maybe not prompted their sell of it, but it made it difficult. And there were public letters and op-eds basically saying, “How could a Jewish family own this thing that is American?” Various different attempts to get either the government or some other entity to own it. Could you give us a little bit of that story?

Frank Cogliano:

Yeah, that’s an unfortunate part of this story. And you’re right. And of course, between approximately 1890 and the early 1920s when this foundation is created, there is a period of mass immigration to the United States, mainly from Southern and Eastern Europe. And so whereas most immigration to the United States, voluntary immigration that is, prior to that period had been from Northern and Western Europe and the British Isles, this so-called New Immigration was mainly from, as I say, Southern and Eastern Europe. And many, many millions of those immigrants were non-Protestants. Many were Catholic, but a large number of them were Jews, and they were Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe. And there was, as we know, a kind of backlash against that so-called New Immigration that culminated in a rebirth of the so-called second KKK in the 1920s. So there’s a great deal of antisemitism kind of in the air in the United States in the early 20th century, especially in the early 1920s.

As you say, there was a good deal of criticism of the Levy family, despite the fact that they saved Monticello and were the caretakers of Monticello, basically saying, “They’re not really worthy of owning this iconic American site, this site that kind of represents what the United States is.” Sometimes it was explicitly said because they were Jewish. Other times it was left unsaid because frankly it didn’t need to be said. In our current vernacular, it was a dog whistle that everybody understood. And at one point, Jefferson Levy said that he would not sell the house under any circumstances because of this. He eventually acquiesced and sold it to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation in 1923. Many of whose members, I should say, original members, were themselves Jewish. And so the debate about Judaism or the association of Monticello with Judaism, it’s a deep history and it’s an important history and it’s an American history and it needs to be remembered.

Rebecca Burgess:

Absolutely. Once again, these historic homes of presidents and especially Monticello, is so tapestried, I would say. Maybe that’s not the right word, but it’s the best metaphor I can come up with, which is how interwoven with so many different facets of the America story, the religious liberty, the education, the political, the social, the questions about slavery and race, and the dichotomies that we have had with professing certain ideals and aspirations, and then how we have failed or succeeded in achieving some of them. And this gets to, I think, maybe Jefferson himself, of how complex of a character he is intellectually, politically, and, of course, definitely privately. He had so many public personas. He is a young Virginia land owner, colonial elite, and Virginia State delegate. Importantly, of course, I have to say this: a member of the House of Burgesses. This is how I tell people in Virginia how actually to pronounce my last name. It’s the one state where you see the light bulb click. “Oh, okay.”

Rebecca Burgess:

… That you see the light bulb click a bit “Ah, okay.” It’s not a hard G. Anyway, but then of course, he’s also Virginia Governor, drafter of the Declaration of Independence and Ambassador to France, US Secretary of State, Vice President, President of the United States, founder and architect of the University of Virginia, a founder of the United States. Which story is told at Monticello of this public persona, this man? And when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation was officially incorporated, how did they choose one of these personas or just the whole man and how did they go about stating what their purpose was with this foundation and what they hoped Monticello to be?

Frank Cogliano:

Yeah, that’s a small question. Thanks.

Rebecca Burgess:

You’re welcome.

Frank Cogliano:

And as you say, it’s a pretty full CV he’s got. He did a lot of things. I think when the foundation is originally established, Jefferson’s reputation was actually at a low point. So Jefferson’s reputation has risen and fallen over the past two centuries since his death. He is in a low point after the Civil War, down to about the ‘1930s, really the ‘1940s, I would argue. And the reasons for that are complicated. To some extent, it’s just the ebbs and flows of history. He’s slightly implicated because of his association. He’s tainted with secession. There’s a hint of secession in some of his writings in the ‘1790s when he was the main author of the Kentucky Resolutions and suggested that states could nullify federal legislation they didn’t like. And so I think it’s slightly unfair to hold him responsible for a civil war that happened a generation after he died. But there’s an association there that doesn’t help him.

And his reputation is at a low point. I don’t want to overstate this because he’s always had admirers, men like the levies, like those men and women who helped establish the foundation in the early ‘1920s. But he’s at a relative low point. But the founders of this foundation, it’s a terrible formulation, forgive me, are committed to what we might call the tombstone legacy. So for people who visited Monticello, you’ll know despite that amazing CV, there are three things on his tombstone, author of the Declaration of American Independence, as he puts it, author of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom and Founder of the University of Virginia. And that tombstone legacy, if you will, I think neatly encapsulated for all the things he could have said.

He didn’t say I was a two-term president. He doesn’t put the Louisiana purchase on there. It’s a very elegant summation though, because what you have there is a commitment to… So let’s break these down. In terms of the Declaration of Independence, you have a commitment to political independence and really, small are Republican self-government. Basically, we should be able to govern ourselves. That’s what the declaration stands for. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the first time in American history that we have a separation of church and state and one of the first times we get it in modern history and globally. And that’s a commitment to freedom of thought. And separation of church and state is about protecting the state from the church and the church from the state. But it’s also a commitment to freedom of thought. And Jefferson famously says, and this is one of my favorite lines of his, in the notes on the state of Virginia, “It doesn’t bother me whether my neighbor believes there’s 20 gods or no God, it neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” And so that’s an important legacy there.

And then finally, in the founding of the University of Virginia, we have a commitment to education as the way you perpetuate those first two things, which are the point of having society, right? So political independence, Republican government, again, small arm, we’re not talking partisanship here, freedom of thought and education is the silver bullet, that’s how we get it done. So that tombstone legacy is really what the foundation is committed to in its early years. And it’s about, as you said, preservation as well as education.

And so the first thing they’ve got to do is they aspire to restore the house to the way it was in the early 19th century, excuse me, when Jefferson was living there. So the house you visit today approximates the way it would’ve been in about, I don’t know, ‘1819, ‘1820. And so they have to remove a lot of the modern furnishings and the modern decor because the levies and others have lived there in the succeeding century. But they’re really committed to this vision of presenting the house as it was when Jefferson was living there in retirement. But they’re crucially, with regard to your question about education, interested in conveying, I think in those early days, that tombstone legacy as being what Jefferson stood for.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. So in terms of education or presenting the house as a… So I earlier used the quote, it’s a Jefferson’s quote that it’s an essay in architecture, but it’s an essay of Jefferson’s thought as well. And so uncovering that through the tour and the objects there. So as you mentioned, you have the physical objects that need rehabilitated, and that’s its own interesting question, and maybe I’ll start there before getting to how the foundation starts thinking about the house tour, which becomes the pivotal or central encounter with Monticello. So how do you in the early ‘1900s, start going about trying to find these household objects that may have been Jefferson’s. And along with this, which we haven’t really mentioned, where is Jefferson’s family, his descendants or any of the descendants of the slaves circulating in this story? Do they have some of these objects? Are they coming forward? Are they happy with this direction? Are they staying away because it’s a place of pain and suffering for them?

Frank Cogliano:

Well, okay, that’s another big set of questions. Thank you, Rebecca.

So let me try and address them. So in terms of restoration, initially, what they do and the work is done by a husband and wife team, a lot of the early work named Fiske and Marie Kimball and the Kimball’s are both… Well, Marie Kimball’s a curator, and Fiske Kimball’s an architectural historian. And they seek to restore the house. And they basically take the view that anything that wasn’t Jeffersonian shouldn’t be in the house. And so initially, what happens after the foundation buys, is the house is actually pretty sparsely furnished because there aren’t that many things that are immediately Jefferson era or Jefferson related in it initially. And then the curators at Monticello just do amazing detective work over the next century tracking stuff down.

And they contact descendants. And in the first instance, mainly white descendants. And I’ll get to black descendants in a moment. Mainly white descendants in the first instance who say, “Oh, I’m a descendant and I’ve got this china that I think came from Monticello.” And they spent a lot of time really, really carefully tracking down the providence of goods that are brought to their attention. And because Jefferson was such a meticulous record keeper, because we do have accounts of how Monticello was furnished, they had material to work with and they spent a lot of time trying to track that stuff down. And they do an amazing job. And if you visit the house today, it’s got a lot of Jefferson’s stuff in it. Sometimes, they had to give people bad news saying, actually that desk you have is not Jefferson’s. And it was bought at Sears and it came from Sears in ‘1905. And so they have to give people some bad news and they also have to negotiate with people about whether they’ll loan stuff to Monticello or sell it and so on to the foundation.

But he folks who work here did, especially the curatorial staff, have done an amazing job of restoring the interior of the house. And the house you visit today, apart from its aesthetic appeal, it’s beautiful. Also, it’s pretty accurate. And so if you visit, just to give one example, they’ve got a substantial number of the books in Jefferson’s library. So what they’ve done is where possible, they found Jefferson’s actual books and acquired them. In other cases, because Jefferson was a meticulous record keeper, we know the books he owned, including the particular editions he had. And so where they haven’t been able to get Jefferson’s copies, they’ve got the equivalent first edition, the relevant edition of the books he owned. So the library you see when you visit the house today is a very accurate recreation of Jefferson’s library. And the books that are behind glass are actually the ones that Jefferson owned. The others which are still rare in themselves, are the equivalent editions that Jefferson owns. So that’s one way to illustrate the point.

As far as descendants are concerned. So white Jefferson descendants, many of whom had inherited Jefferson-related furniture and Jefferson’s possessions, were happy to collaborate with the foundation. As far as the descendants of those enslaved at Monticello, including of course, some of whom were descended from Jefferson himself, there’s less material artifacts have survived because those people, their fore-bearers, were not allowed in most cases or did not inherit material from the original house.

On the other hand, what they took with them, and there’s a project at Monticello that falls within the International Center for Jefferson Studies now, called Getting Word. It’s an oral history project. What they took with them was their own experiences and their own family traditions of life at Monticello. We have to remember, Jefferson didn’t live at Monticello alone. There were approximately 200 enslaved people there at any time throughout his life. And so in fact, this is one thing that I often remind people of. It’s a predominantly black space when he lives there. It’s a site of black history in America. It’s not just Jefferson’s home. And so they take their memories and family traditions of their associations with Monticello with them.

And the Getting Word project, which has now been operating for three decades here, is tracking down the descendants of people who were enslaved at Monticello and collecting their family traditions. And it’s amazing how consistent these are. These are people scattered across the United States and in some cases, across the world. But the family traditions and the oral traditions within those families about the life at Monticello and their fore-bearers are a remarkable resource, but also remarkably consistent. And I’ll give you one example that’s really, really exciting, if you’ll indulge me for a second?

Rebecca Burgess:

Absolutely.

Frank Cogliano:

So one of my colleagues up at Getting Word, the current director, a young scholar named Andrew Davenport, his team got a call a few weeks ago from a Ph.D. student at the University of Northern Kentucky who basically said, “Hey, I think I’ve met somebody you need to talk to.” And it turned out it was a gentleman in question who lived in Cincinnati. He’s an older gentleman there who had in his possession he’s descended from one of the enslaved people at Monticello. He’s descended from the Fossett family, Joseph Fossett at Monticello. He had in possession his fore-bearers freedom certificate and a letter between two people, again among his fore-bearers, family letters within his family from the ‘1840s. It’s the first letter we’ve ever encountered, ever discovered between two people enslaved at Monticello.

And this gentleman in Cincinnati had them in his possession. He’s an older gentleman, as I said. And Andrew had to go out to Cincinnati to meet him and photograph these documents, interview him, and add another interview to the Getting Word archive. But we’re still making new discoveries among those, the descendants, both white and black, who lived and worked here. And that’s one of the most exciting things about the work at the foundation. Sorry, I’m getting slightly away from your original question, but it’s such a great story. I’m happy to share it.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. And Joe Fossett himself is a very fascinating figure. If I remember right, he’s one of the slaves who was sold during that public auction who returns before his death. Am I right?

Frank Cogliano:

Yeah, that’s right. That’s right.

Rebecca Burgess:

And he has this interesting, and it’s… Well, it’s very interesting for me. And I guess here I should have said, I am a member of the young advisors of the Thomas Jefferson Monticello Foundation, which is a group that they pulled together in anticipation of the 250th anniversary of the founding of America, the Declaration of Independence in ‘2026. So I am involved in Monticello other than just pure intellectual interest and love of America and American history and American Founders. But anyway, if I remember right, the Joe Fossett story is so interesting because it brings up this question of slaves who saw Monticello also as their home. And that question of home and returning to home and the ability to return home and how that adds a wrinkle into the complexity of this place called Monticello and race relations.

Frank Cogliano:

It does. It does. So the metaphor I like to use is that the mountain has two sides. And so we talked about Jefferson’s gravestone a few minutes ago, and as I said, when the foundation was first established a century ago, that was the main focus. We remain committed to talking about that legacy. It’s incredibly important. It’s the reason we’re here, frankly. It’s the 250th of what we’re celebrating in two years time, right? Or three years time. It’s that legacy. However, so if you stand on the steps on the West Portico, if you’re standing on those steps, and I had the privilege to speak from there a few weeks ago, and it’s an incredibly powerful place. It’s the place where Jefferson organized races on the west lawn for his grandchildren. It’s the place where 50 to 60 new citizens take the citizenship oath every 4th of July now. It’s the place where Franklin Roosevelt spoke on the 4th of July, 1936. It’s the place where those people were auctioned in ‘1827.

So it’s an incredibly powerful place. And you can look in one direction, you can’t see it, but if you look several hundred yards away in one direction is Jefferson’s grave. Several hundred yards away, approximately the same distance in the other direction is the East Road burial ground where people who were enslaved at Monticello are buried. Not all, but some of them and their descendants. And the point I would make is you can’t have half a mountain and we now have to pay attention, and we do. And we want to pay attention to both sides of the mountain and both of those… So that spot and the-

Frank Cogliano:

Mountain and both of those. So that spot and the kind of two sides of the mountain that are represented by those two graveyards are incredibly important. And they are important because Monticello is America writ small because if they will… if you will, they’re a metaphor for the country in my way of thinking. So that’s how I like to think of it. And I think we now tell both of those stories because those stories are so important. They’re also interlinked. We have four accounts, four life accounts from people who were enslaved at Monticello. Memoirs or autobiographies and so on.

Rebecca Burgess:

Okay.

Frank Cogliano:

Each one of them mentions the Declaration of Independence. They don’t mention that they love Jefferson. I mean, it’s too much to say, “Hey, I loved my enslaver, or I loved my father.” It’s a complicated history, right? But they do associate Monticello with, these people who were enslaved here, was the Declaration of Independence. So to some extent, I would argue in response to people who say, “We need to…” I don’t like this phrase, cancel Jefferson, whatever it is. Well actually, at least the testimony we have from some of the people who were enslaved here, and they don’t speak for all of them, of course, but the anecdotal evidence we have is the part of Jefferson’s legacy they identified as important. And the reason they associated with Monticello, despite the fact it was where they were enslaved, is the Declaration of Independence and its premise… and its commitment to equality not fulfilled in Jefferson’s lifetime, not entirely fulfilled in our lifetimes. But that’s the takeaway.

Rebecca Burgess:

And I think you can argue that it is only respect, true respect for us to acknowledge that the Declaration of Independence, in their own words, played a large role in their association with Monticello and how they thought of Monticello. Maybe not lived reality, of course, as you were mentioning, but if it wasn’t so important to them that they themselves mention it in their accounts-

Frank Cogliano:

Right.

Rebecca Burgess:

… we should respect that and not cancel their own affiliation with that document, I would say. I’ve been thinking about this. You’ve mentioned the tombstone legacy and how it doesn’t mention such amazing things as the Louisiana Purchase or the Lewis and Clark expedition, and yet the house itself in a way almost has that legacy.

You enter in, and that first room is this almost museum of America. It has all of these artifacts, taxidermy, hides, horns, bones that were found throughout America. There are, if I’m remembering, it had a bison skin, which is decorated from North American Indians. And so in a way, the house is its own legacy or testament into America. And if you could tell us about the development of the house tour and how that has over the years really deepened into, instead of just pointing out this artifact, that artifact, this room, that room, tries to tell the story of the various storylines in residence of Monticello, and moments… and political moments, and political theory moments of the house.

Frank Cogliano:

Sure. I mean, Monticello isn’t just a museum today. It was a museum during Jefferson’s lifetime. He had a lot of visitors and tourists who came through, and came to see him. And he recognized that. And that entrance hall that you referenced was decorated, especially with indigenous artifacts. But there’s a map of Africa. There are various maps, there are fossils. And when people were kind of cooling their heels in the entrance hall, they were meant to learn a bit. And to a very real extent, that legacy continues today.

And you are right. The primary way that the Foundation communicates information to visitors is through the tour. The tour of the house, but now also what we call the Plantation Tour. There’s a tour of Mulberry Row, where the enslaved people lived and worked. There are architectural… sorry, archeological tours as well. But the tours are the main way that the Foundation communicates with the public.

And one of the things I liked is that I have a huge amount of respect for the tour guides at Monticello. They’re very, very highly trained. They do a lot of reading, I can tell you that. And they’re really put through their paces before they’re allowed to give tours to the public. And one of the things I say, because I like to speak to the guides, is their work reaches far more people than the work of people like me. We write books that come and go and… You know?

Rebecca Burgess:

Yes.

Frank Cogliano:

Get read by our mothers, maybe, and that’s about it. Right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Or just by one academic library.

Frank Cogliano:

Right. Exactly. Exactly.

Rebecca Burgess:

Yes.

Frank Cogliano:

One only needs to get one’s royalty statements to realize how unimportant we are.

Rebecca Burgess:

About this much.

Frank Cogliano:

But they reach so many people, and it’s incredibly important what they do. And the house tour is about 45 minutes, and they have a huge amount. It’s a complicated place. It’s a complicated legacy, as we’ve been talking about, to cover. And the tours evolved a lot over the years, and it’s become, I think, more subtle and nuanced. They deal with matters of race and slavery. They deal with Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemmings. There’s a real challenge on the house tour, which is you’re trying to… or they are trying to convey ideas with objects. It’s too easy to say, isn’t that a pretty painting?

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Frank Cogliano:

Because it is a pretty painting, or, look at that architectural feature. But what they’re trying to do, and they do supremely well in my view, try to say, okay, what does all this add up to? What does it mean? What was Jefferson trying to tell us in decorating his house as he did? But as I said, a crucial element to this, I think as well, is, and I can’t urge this enough for people listening to this, don’t just take the house tour great as that is. Make sure, and it’s included in the ticket, you take the plantation tour too because the people who give those are amazing. And you get a fuller idea of what was going on at this mountaintop and the sense of it not just as the home of a really, really important individual, but a community, and how it operated. And that’s conveyed by the tour. And that’s the way the Thomas Jefferson Foundation engages in the work mainly of education to hundreds of thousands of people every year. It’s the most important thing we do.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. And I should just say to our listeners as well that the guides not only, as you put it, are put through their paces, but they’re given research time every week, where they are not just encouraged but required to continue their learning and encouraged to explore their own interests in Jefferson. And so there’s actually not a script, one common script that they’re given for their tours. And so you can go five different… 10 different times to Monticello and get a different tour emphasizing different things. One can be very much about the Declaration of Independence. One can be very much kind about the tinkering, knick-knack aspect of Jefferson the explorer, if you will. And another can be very much about the life of the enslaved, or his family, and the complicated relationships there going on. So that, I think, is always valuable to emphasize and to highlight and clarify because as we’re living in very polarized, polarized times and how one presents a story from history, it’s impossible to say every single aspect and every single nuance in, as you mentioned, 45 minutes.

And there’s also a suspicion that there’s… brainwashing is not the right word, but a script that is meant to be shoved down people’s throats. And that’s really not the case going on. And it’s a very difficult thing for presidential museums, homes to do this right now, or historic places to try and tell their story with truth and accuracy, but also nuance.

But to go a little bit further down the road of this educational aspect, as the Foundation in those first decades of the 20th century gets its feet underneath it financially, and is able to restore the house and get more visitors, they’re also working on revitalizing that… a scholarly image of Jefferson. And the Great Depression is happening suddenly, and they’re still able to pay off their debts, and raise this interest of Jefferson. And suddenly, biographies and books start showing up about Jefferson. And meanwhile, FDR, President FDR comes along just around the time that discussions are being held in D.C. about a memorial in D.C. And he is very pivotal in changing the nature of that memorial into a Jefferson Memorial. I was wondering because was that 1943, so we’re not quite at a hundred years there with that, but if you could tell us a little bit about that story, and the FDR, World War II connection with Thomas Jefferson and Monticello?

Frank Cogliano:

Sure, sure. So FDR was a great admirer of Jefferson, and as I said a few minutes ago, he visited Monticello. He actually visited this area a lot. The house I’m sitting in, Kenwood, was the home of… They didn’t have the role of chief of staff then, but he was the equivalent of Jefferson’s… sorry, FDR’s chief of staff, a man named Edwin Paul Watson. And Paul Watson was a close confidant of FDR’s. And so FDR came here a lot, but he spoke at Monticello on the 4th of July, 1936. So FDR was a great admirer of Jefferson.

And in 1943… 1943 was the bicentennial of Jefferson’s birth. Jefferson was born in 1743. And then as now, in the approach to that, people said, we ought do something about this in the same way we’re saying about 2026. How are we going to celebrate this? And FDR was a very strong advocate for the building of what’s now the Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C., including picking the quotes that are carved in the memorial. And of course, that memorial was built during the Second World War, and FDR believed that Jefferson was the kind of apotheosis of the values for which the United States was fighting, and its allies were fighting in the Second World War.

Jefferson, the bicentennial of Jefferson’s birth and the dedication of the Jefferson Memorial on one hand can be seen as of their time, but that also marked a kind of change beginning… I mentioned a few minutes ago that Jefferson’s reputation was kind of low before that. The comeback starts during the Second World War and particularly after the Second World War. And what we see is… A couple of things help account for this.

First of all, because of the Second World War and then the subsequent Cold War, those values for which Jefferson… or with which Jefferson identified, that tombstone legacy, let’s say, suddenly seem really important. Right? We’re not blaming him for the Civil War anymore. Instead, we’re saying, actually, this is what we’re about in the fight against fascism and then the contest with the Soviet Union after the Second World War. So we get that.

Also, one of the things that starts… There’s another kind of monument that started in 1943, which is the publication of the papers of Thomas Jefferson. You can actually see… You can see them. Our listeners can’t, on the shelves behind me. So the Princeton edition of the… the modern edition of the papers of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Julian Boyd, begins in 1943. It’s still ongoing. We’re nearly there at the end, but we’re going to get there hopefully soon. But that makes Jefferson’s writings available to scholars, which is going to energize scholarship in the second half of the 20th, or in the middle decades of this 20th century, and continues to this day. So we get that.

So that’s the kind of big-picture stuff. And we get publications like Dumas Malone’s… the first volumes of Dumas Malone’s six-volume biography of Jefferson. The first volume was published in 1948, the last one in the early 1980s. So we get this… as I say, this efflorescence of Jefferson scholarship. I do think the Foundation plays a role in this, especially in the latter part of the story, with the creation of the International Center for Jefferson Studies. I’ll get to that in a minute.

However, we also have this key connection: the Foundation endows a chair, the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation chair in history at the University of Virginia. So Dumas Malone holds it, and then Merrill Peterson, then Peter Onuf, and currently, it’s held by Alan Taylor. And so what we have is Jefferson scholars at UVA, Jefferson’s university, who really energized the study of Jefferson, both through their own publications and through their supervision of Ph.D. students or advising of Ph.D. students.

So what we have is an infrastructure around Jefferson that emerges supported by this Foundation, but… through funding that chair, but also when we get to the ’90s, the creation of the place where I sit today, the International Center for Jefferson Studies, which through its close links to UVA and particularly UVA Press has served as a home for scholars and scholarship, but also helped those scholars find a venue to publish in.

And so there’s been a kind of infrastructure, if you will, it’s not an accident. There’s a reason that Jefferson Studies has boomed over the past 30 years. In part, those foundations were laid in the middle of the 20th century. But the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has helped build on those mainly through ICJS, but not only its association with UVA and elsewhere. Sorry. That’s a lot.

Rebecca Burgess:

No, it’s all good. And we wanted to get to this, as you mentioned at the beginning, talking about these last 30 years and how fruitful they have been. And you mentioned the international aspect of it. We are so inwardly focused, famously or infamously, in America on ourselves and on our own, but what does it look like coming from the outside? What other country… What are they looking to Monticello and to your center for about Jefferson? Is it… and the relation to the Declaration? Is it all in relation to the Declaration? Or are there just multiple different… you know?

Frank Cogliano:

We’re back… We’re back to the two sides of the mountain, Rebecca.

Rebecca Burgess:

Okay.

Frank Cogliano:

As you know, academic historians and one of the real jewels of the crown of American historiography since the Second World War has been the development of the historiography around slavery, slavery and race. And we’re the best-documented plantation probably in the world. And so we attract a lot of scholarship in that area. But we also attract a lot of scholarship on the tombstone legacy. So I will give you an example. At the moment, this is a random example, but I think it’s indicative. We’ve got several fellows here at the International Center working on a variety of topics. And by coincidence, one of them is a woman from the Netherlands who’s working on the relationship or the interaction between the French Army and the Americans, Jefferson and Washington, during the War of Independence. The other, we’ve got a Danish scholar here, who’s coming to us from a house museum in Denmark where…

Frank Cogliano:

… here, who’s coming to us from a house museum in Denmark where they are struggling, unsurprisingly, in the current moment to reckon with their history with race and slavery. And she’s here studying this from a museum studies standpoint to say, “How have you dealt with this?” And obviously, we’ve got generations of experience dealing with questions of race and slavery. We’ve got another scholar here from Oxford who’s writing about Jefferson’s relation with Condorcet, the great philosopher in the French Enlightenment. These just happen to be this month’s fellows. Next month’s fellows will be different. We’ve got a long-term fellow here from the University of Richmond who’s working on a really interesting project about religion in the Northwest Territory in Ohio and relations between Indigenous people and the Shakers. It’s everything and anything, but those just happen to be our current fellows. But to illustrate, we happen to have a good crop of international fellows at the moment, so I think that as an answer to your question, or a way to answer your question, is just that random sampling.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. Jon Meacham has said that experiencing Monticello is as close as you can get to having a conversation with Thomas Jefferson. So, in a way, bringing those international fellows to Monticello is… Well, I think that’s a really neat thing.

Frank Cogliano:

I agree.

Rebecca Burgess:

But a little on that note and on the question, you brought up the Northwest Ordinance, which we could have a whole other podcast on. It’s one of the forgotten documents, I think, of America’s freedom and really needs a lot more attention paid to it. But something that struck me is that when Jefferson started to build Monticello and his father, that was the frontier, and that is the western divide, if you will, and they’re looking out on this vast expanse, and they’re looking ahead. Jefferson has always struck me as being full of optimism and then, of course, having to get his nose rubbed in the sand of reality as he becomes president and realizes you do need a manufacturing class, you can’t just have these farmers if you want this type of free society, various different aspects like that.

But as we’re all looking forward to the 250th anniversary, thinking of Monticello still as a frontier of scholarship on Jefferson and on the declaration and its role. Where is Monticello wanting to point us to, if you will? What types of conversations, what conversation with Jefferson is Monticello hoping it can open our eyes to?

Frank Cogliano:

I think… We have a lot of discussions about this internally, as you can imagine. I think we, and maybe I’m speaking for myself here more than the foundation, but I’ve been privy to these discussions. We really want to center Jefferson in the discussion of the 250th. But in so doing, we need to do so with care for both. It’s a complicated legacy, as we’ve already discussed. But what we’re really talking about is it’s the 250th anniversary of what? The Declaration of Independence. And so, just like those enslaved people who make that connection between Monticello and the Declaration, I think we’ve got to do that ourselves because that’s the core document, that’s the foundational, that’s the mission statement for the United States. And that’s the reason we remember Jefferson, and that’s the reason this place is so important.

All the other stuff follows from that, and all the other stuff requires our consideration. The other aspects of the Tombstone legacy, as I call it, the other side of the mountain, when we deal with, “Okay, hold on a second, Mr. All men are are created equal. What about the 607 people you enslaved?” That’s not a small question. You talked about the frontier. “Hey, whose land was your house built on?” These are important questions we have to talk about, but they all follow from, it seems to me, that foundational moment and that foundational document for which we are all indebted to Jefferson. And this is why I don’t like talk of cancellation. I don’t like zero-sum arguments where it’s got to be all one thing or the other. The past is complicated, the present is complicated, and people are complicated. Jefferson’s definitely complicated. But I think the message and the centering of the declaration and Jefferson’s authorship of the declaration is the real message and the takeaway for the 250th, which the word is, Rebecca, semi quincentennial.

Rebecca Burgess:

I know, I know. See, you knew I was avoiding using that word because it’s such a tongue-twister. I always take the easy route and just say the 250th.

Frank Cogliano:

No, most of us are doing that.

Rebecca Burgess:

Semiquincentennial. I just said it, but your words make me want to ask this question of you because I think I already know the answer, but I think it’s helpful to raise the question for our listeners. Is then Monticello actually a museum? Is it a shrine, is it a memorial? Is it all of these things, and or is it something else?

Frank Cogliano:

I think it’s all of them. I think it’s a museum, but I don’t want people to think, “Oh, it’s a dusty place you shouldn’t go to.” I think it’s those three things, but it is a shrine. It’s a shrine at Jefferson, but it’s also a memorial to the people who were enslaved here. And we mustn’t forget that. And we’ve dedicated a new commemorative site in the past few months that names those who were enslaved here, the names we know. We’ve left space for those we don’t know, which is telling. So it’s all of those things, but I think it’s something else. Again, I think it’s a place where Americans can come together and have difficult conversations. Frankly, the conversations we’re presently unwilling to have or unable to have, because its one of the few places… Because of the great sort, and because we all bowl alone, we basically talk to people we agree with.

We’ve sorted each other in the red and blue, and we don’t talk to each other, we talk past each other. Not here because hundreds of thousands of people come here. I love talking to people in the parking lot and saying, “Hey, where’d you come from today? And why are you here?” If they want to engage me, sometimes they just say hello and keep going. But what’s fascinating to me is they come from all parts of the country. I don’t want to make any presumptions about what their backgrounds are or what their beliefs are, but this is a place where we can also… It’s always been a place of having hard conversations. Jefferson liked to have hard conversations. Crucially, you also believe they ought to be conducted with civility. And I think we need that.

Rebecca Burgess:

And with wine.

Frank Cogliano:

Yes. That helps.

Rebecca Burgess:

No, no. Good fair. Okay. Along those lines, to final, or as we approach the end of this conversation questions, and before I ask you about the book that you are currently writing on Jefferson and George Washington, do you have a favorite story or quote either specifically related to Monticello or to Jefferson that is not necessarily well-known, but that just encapsulates for you some of either the richness, the complexity, or the joy, the wonders of this “essay” of America?

Frank Cogliano:

Shared one of my favorite quotes, the one about, “I don’t mind if my neighbor believes there are 20 Gods or no God.” That’s a favorite from the notes on the state of Virginia. You got to love, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness ” is a quote, and “All men are created equal.” And women, I would add. But I also like in the context of what I just said. One of my favorite quotes, and Jefferson himself struggled to live up to this, but I think it’s an important one, is, “I never considered a difference of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy as cause for withdrawing from a friend.” And I really like that quote. That’s my current favorite. I mean, he’s got some great ones, but that one has really stayed with me as I look around in the current moment. And I think if we all thought about that, that might be good. Sorry, I’m sounding preachy now.

Rebecca Burgess:

No, no. I was just going to say, immensely relevant for us today. And so, you are writing a book on Jefferson and George Washington, and you claim that it is the first of its kind. Can you tell us what this book is? It’s coming out in the spring. I think that our listeners will be very interested in this book. I know I am.

Frank Cogliano:

It’s coming out-

Rebecca Burgess:

More people than I will be.

Frank Cogliano:

I think the publication date is February 20th, and it’s called A Revolutionary Friendship. It’s about the relationship between Jefferson and Washington. Jefferson and Washington had a 30-year relationship that was mainly amicable. I mean, one of the things I’m looking at in this book is their friendship, and it’s ebbs and flows, because, as many people will know, it ended badly. They were estranged at the end of Washington’s life and they never reconnected because Washington died soon after in 1799 I think we’ve made a mistake and projected that back and looked for this throughout, and I just don’t believe that. I mean, one of the things I did, I set out to read their correspondence in order, starting at the beginning and going to the end. And it’s just simply not so that they hated each other throughout their lives. They actually collaborated quite closely on a number of things, and quite productively, and quite happily.

But they did differ politically and they differed over significant things, and I talk about that. But I talk about their relationship born of the revolution and eventually destroyed after the revolution and how and why that happened. And it’s not a metaphor parable for our time, but I do think it might have something to tell us in this time. I’ll be launching it here at Monticello on February 17th, right around President’s Day, and you’re all welcome to come.

Rebecca Burgess:

Oh, I’ll try and get myself there. Well, Jefferson famously died on July 4th, 1826, and he was full of foreboding about the violence he saw, of course, ahead. But he had optimism too about the American project and the project of freedom and equality that he had tried so hard to enshrine in the Declaration of Independence. So as America looks ahead to the 250th anniversary, and you’ve kind of answered this, but how can Monticello help us to reengage with our nation’s aspirations and complicated legacy?

Frank Cogliano:

I think it’s a place where we need to talk about this stuff. We have been doing that for the past century. We need to be at the center of a public conversation. We have a unique opportunity here because the eyes of the country and the world will be on this place because of its association with Jefferson, and we have a unique opportunity to help engage in, I think, a project of civic education to talk about the core values that we all still share as citizens of the United States.

Rebecca Burgess:

Well, thank you so much, Frank, for that, for joining us for the Hopeful Words, and a happy 100th birthday to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Monticello, and of course, gratitude for all of those whose study American political thought and history, for the work and the help that the foundation has given us the past 100 years and in revitalizing recapturing, relearning who Jefferson was. So thank you again, Frank, for joining us.

Frank Cogliano:

Thanks, Rebecca. Here’s to the next 100 years.

Rebecca Burgess:

Yes, exactly. Cheers with some wine again. All right, so that was Frank Cogliano the Interim Saunders director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello. I am Rebecca Bridges and this is Liberty Law Talk. Thank you for joining us today.

Brian Smith:

Thank you for listening to another episode of Liberty Law Talk. Be sure to follow us on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts.