The State of the West

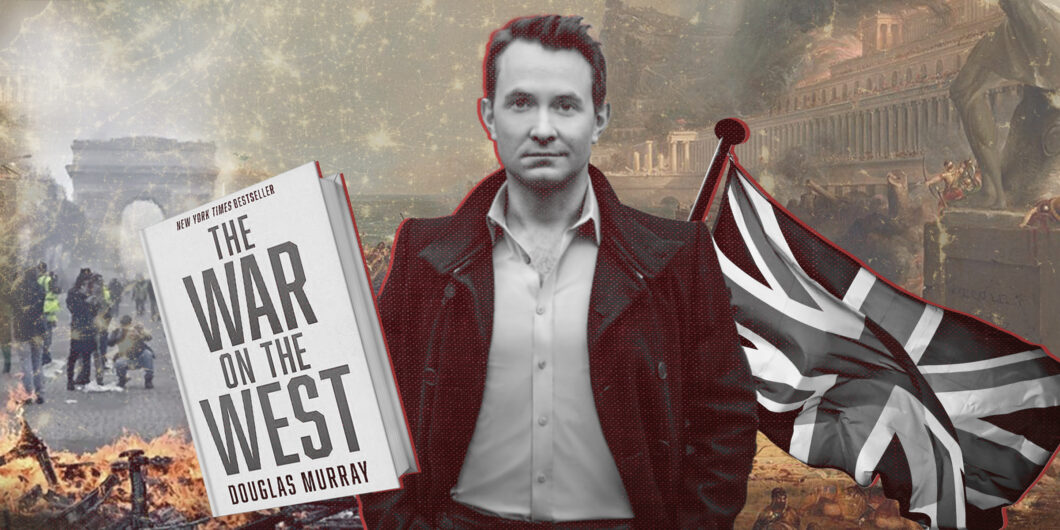

Douglas Murray joins Law & Liberty Senior Writer Helen Dale to talk about the state of racial discourse, national conservatism, and his recent book, War on the West.

Brian Smith:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. This podcast is a production of the online Journal of Law & Liberty and is hosted by our staff. Please visit us at lawliberty.org, and thank you for listening.

Helen Dale:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. My name is Helen Dale, and I’m Senior Writer at Law & Liberty. With me today is Douglas Murray, Associate Editor of The Spectator and author of seven books, including The Strange Death of Europe, The Madness of Crowds, and the subject of part of today’s interview, The War on the West. Thank you for joining me, Douglas.

Douglas Murray:

It’s a great pleasure to be with you, Helen.

Helen Dale:

Without wanting to pin the conversation down the way an entomologist pins insects in a display case, the following questions came to mind when I was reading The War on the West and also covering the UK National Conservatism Conference for The Australian and for other outlets, at which you spoke: while reading the first third of the book, broadly speaking, the race and history sections, I became increasingly alarmed by what seemed to me to be genuine anti-white racism, and by way of throat clearing, letting you know that I’m really quite reluctant to use that phrase. However, and I’m afraid this did involve taking photographs of pages and sending them to an academic friend who specializes in the relationship between ideology and genocide, and the material you cite is nothing short of monstrous. My friend argued that if you draw attention to racial distinctions and then assemble them in a moral hierarchy, you have racism.

We then went on to discuss how other classic genocidal tropes include depicting people as vermin, parasites, or disease, and I have to say, I think it’s fair to say that you’ve unearthed plenty of that in the first part of The War on the West. Both my academic friend and I are familiar with the film you discussed, Single White Men. At the time it came out, we both thought it tended to fall into the same category as Jewish comedians telling Jewish jokes or Chris Rock’s routines taking aim at aspects of African-American culture that would be off limits to others. It’s possible, too, that Karl Marx can be excused for some of his comments about Jews because he was himself Jewish. However, the great bulk of the anti-white material you discuss is not funny or attempting to be funny, and often it’s also directed at whites by non-whites. How serious is this anti-white racism? And depending on your answer to that first question, what is a reasonable public response?

Douglas Murray:

I think it’s very serious. It’s the only permissible racism in our day. As I try to show in the opening chapters of The War on the West, there is almost nothing that you cannot say about white people as white people, up to and including saying that the world would be better off without white people and that something should be done about that. By contrast, almost every other form of racism against any group of people is understandably and legitimately regarded as being effectively reputation-ending, if not career-ending. You can’t go about saying things about people who are black if you’re not black.

And by the way, the example you give of, as it were, a black comedian saying things about black people bit, Dave Chappelle, and so on, even that is effectively innocent fun. Michael Moore, who you mentioned, I cited as an example of this going back some way, this sort of anti-white racism, by contrast, says things like, “Every problem in the world, look at it and behind it you’ve got white men,” just every single problem in the world, every genocide, every war, every battle, every ugliness is all to do with white people. Obviously, as I mentioned in the book, Michael Moore is one of those who doesn’t realize that other people have agency and can muck up the world and their own countries in their own ways, and he’s obviously never heard of numerous countries, including North Korea.

Helen Dale:

Well, there’s part of me that wants to say that Genghis Khan is on the line and would like a word.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, exactly. So, there is something different about this in the tone of the claims being made and the simple way in which it’s waved through. Universities are somewhat over-cited in these arguments, perhaps, but they do matter, and I can use it as an example: if somebody stands up at a university and says that Jews are responsible for all the problems in the world or black people are responsible for all the problems in the world, they wouldn’t be invited back. They certainly wouldn’t be a member of the faculty. By contrast, as I give the example of numerous academics who say this about white people, are often not white themselves and draw the most negative possible conclusions and, at least one case, as far as I can see, calling explicitly for violence. I think the problem with this is that it’s grown up under our noses, and it’s the result of a couple of things.

One is something I’m fond of using as an analogy, but simple overcorrection. There was undoubtedly racism in the past. There certainly is racism. Racism exists—it’s one of the ugliest traits of the human species, effectively in out-group dynamics. It’s almost certainly ineradicable, but it’s certainly also able to be diminished; it’s able to be made societally unacceptable. And because there was acceptable racism in the past in countries like Australia, Britain, and America, there seems to be some sort of overcorrection that says, “Well, because there was racism against these groups in the past, we can make up for it by being racist against the people who were thought of as being the racist people.”

Helen Dale:

I found that description of the US. Was he a four-star general? I can’t remember. Yeah, and he’d not heard it before. You had, and I had heard this before. And then he was just sitting there because this was a number of years ago. Was it 2011 or something?

Douglas Murray:

Yeah, around then. He said to me, as somebody said to us on stage, “It’s just two white men speaking.” I’d heard that kind of rhetoric before, but the general who was on my side, the American general, had not, and from his point of view, it was very shocking. I was immune to it already, but I think his point of view was, “But I’m a four-star general. I’ve been in charge of operations in Afghanistan most of my life, for years, and worked in the military for years, and been everywhere around the world, and Douglas Murray sitting beside me, is younger and has had totally different experiences and has done very different things, so how do we become just the same person in the eyes of this other speaker other than if you want to pretend that you can sum up everything about a person in their race?”, and that is racism. It’s a minor example of it, but again, if somebody was to be on stage and just say, “Oh, that’s just two brown people talking,” and-

Helen Dale:

It’s the moralized hierarchy that my academic friend was saying. That, he said, is what’s particularly dangerous. Lots of societies, he was saying, have noticed that people look different and they have different temperaments and characteristics. The Greeks and Romans, who didn’t attach much importance to color, noticed this, but they never put it into a moralized hierarchy, and that’s the danger.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, and there are several different aspects to that, of course: one is the people who you put at the bottom of the hierarchy effectively now, which is to say white people about whom you can say anything. But the inverse of that is the interesting phenomenon of attributing special characteristics that are benevolent or blessed to certain other groups. My friend Coleman Hughes, distinguished black American writer, a distinguished American writer who happens to be black, in one of his first essays, mentioned the fact that at university in America in recent years, some of his contemporaries who were white treated him as though there was something special he knew or some wisdom he especially had by dint of his racial characteristics. Well, that’s also a form of racism.

Helen Dale:

It’s the inversion of the “magical negro” trope.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, it’s as if you’re saying, “In the past, we attributed negative characteristics to this group. Now we will attribute positive characteristics to this group.” Neither is particularly desirable, it seems.

Helen Dale:

How do reasonable people, both commentators like you and I, and ordinary members of the public fight back? If it is this serious, this dreadful rhetoric, how do we fight back?

Douglas Murray:

It has been the norm in our societies that people defend their ideas, particularly if they are inflammatory ideas, in public. We have to find a term for this type of person in our day who throws out unprovable or rather provable lies but who will not defend them in public and just sort of runs away from contests.

Well, I think people just have to call it out whenever they see it, which is how racism of all kinds has been diminished in the past. You make it societally unacceptable. How was racism directed toward other groups diminished in the past? By law to some extent, but more significantly by societal approbation and much else about people speaking in particular ways. I think that let’s say if somebody said something that was racist about somebody of a non-white skin color near you might call it out, and you might also, more likely you would, never want to be near that person again or in their orbit. I would simply suggest it would be the same with this: people shouldn’t wish to be around people who like demeaning people by their racial background, whatever that background is. But I think that it requires a slight change of emphasis at the institutional levels in our countries, which is that this is not acceptable; it’s not an acceptable way to talk. And that when you have a race-baiting academic, like one particular person who I won’t name at Cambridge University, who-

Helen Dale:

Oh, I’m well aware of who you are talking about because this particular individual teaches at the College where my partner went and is a source of irritation in this household, and it’s why my partner’s donations to her old college have dried up.

Douglas Murray:

Oh, I’m pleased to hear that. That’s the sort of thing, and I hope she said that that was why.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

Because it is very important that if you have an academic in a position of authority and of influence over young people, that that person is not allowed to pollute the public square by making race-baiting accusations against all white people, any more than it would be if that person used their platform to say nasty things about black people. I would throw one other thing into the mix if I can, Helen, which is the oddity in our day of a certain type of person we would’ve called public intellectual in the past who doesn’t deserve that term today because they don’t defend their ideas, but who throw out highly ideas about race and then will not defend them. I’m thinking specifically of people like the white author of White Fragility, Robin DeAngelo: she does not put herself forward for debate or discussion, or interview. And she throws out extraordinarily incendiary claims like the claim that white Americans enjoy seeing black bodies being punished.

Helen Dale:

And that’s just a mess of Foucault in there as well. As soon as you see that, “bodies,” word, that’s just a giveaway, isn’t it?

Douglas Murray:

Yeah. But when somebody like her and I would add in somebody like Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Anti-Racist, he throws in extraordinarily nasty generalizations and just will not defend them in public, says, “I refuse to give a platform to anyone who criticizes me.” As I say, it has been the norm in our societies that people defend their ideas, particularly if they are inflammatory ideas, in public. We have to find a term for this type of person in our day who throws out unprovable or rather provable lies but who will not defend them in public and just sort of runs away from contests.

Helen Dale:

Conversational coward comes to mind, but I don’t know whether that’s particularly adequate. Your section on reparations and discussion of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ desire to emulate the postwar reparations Germany paid to Israel actually sent me down a reparations rabbit hole. I discovered there have been enormous and ongoing difficulties in Israel administering reparation monies and also widespread corruption. When the original Konrad Adenauer-David Ben Gurion agreement was entered into in 1952. There were riots outside the Knesset, an extremist attempted to bomb Israel’s foreign ministry building, and a parcel bomb was sent to Adenauer, killing one of his police bodyguards. The spark for the riots and the terrorism was the argument that, as when damages or other remedies have been awarded at trial, a line must then be drawn under the dispute. Lawyers actually have a technical term for this, it comes from Roman law; it’s Res Judicata, literally, “The thing is decided.”

Now, Ben Gurion considered that Res Judicata was necessary for Israel to move forward and to move on, but about half the country disagreed with him and still does. Relatedly, the Claims Conference, which was one of a number of organizations both within Israel and outside it, administering reparations, has been plagued with corruption and maladministration. A distinguished Jewish Australian, the late Isi Leibler, pointed out that the organization’s big-wigs were earning vast salaries while actual known Holocaust survivors around the world were being paid less than the Israeli state pension.

In 2013, the Conference’s funds director was jailed for eight years for his part in a US dollar $57 million fraud. This is the only reparations regime on foot anywhere in the world, and we all know what happened with the reparations regime flowing from the Treaty of Versailles, of course. How does one go about getting it across to people just how difficult and morally complicated this is, even when the history is relatively recent and claimants can be identified? And as a follow-up to that, are there good silver bullet arguments against reparations given the German-Israeli experience? How useful are legal concepts, statutes of limitation, and Res Judicata here?

Douglas Murray:

It’s a very interesting and deep area, which is one of the reasons why I wanted to address the reparations argument because it’s been treated so lightly in recent years, particularly in America. The example of the Ben Gurion-Adenauer agreement is one, and of course, as I say, it happened within a few years of the Holocaust, and there are deep moral and other arguments to be had about that agreement. But if, in the case of reparations to the descendants of slaves, anyone thinks that reparations is a good idea, and an increasing number of people seem to think it is, you are no longer talking about anyone alive who has any memory of the thing being done or of doing the thing, and that throws up very deep organizational issues apart from anything else: who in the American context is deserving of money and who should pay the money?

This is not a theoretical discussion anymore. Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, recently set up a committee to look into reparations in California, and it reported back recently that black Californians who were descendants or potential descendants of slaves should be paid, I think a couple of million dollars each. And others have come up with much higher sums of money that should be paid. There’s, as I say, much to be said because, among other things, you are no longer really talking about people who have done a wrong paying money to people who are wronged; you’re talking about people who look like people who did wrong in the past paying money to people who look like people who were wronged. Add to that the obvious organizational nightmare, which would make the Israeli case look positively straightforward.

Helen Dale:

Oh, it makes the Israeli case look easy. This does.

Douglas Murray:

Yes. First of all, there is a meltdown in America always about whether or not or why more black Americans do not register to vote, and the argument is often that they don’t, in sufficient numbers, produce the required documentation to prove their residency and much else. There was a debate a couple of years ago that Kamala Harris weighed into where she claimed that basically, black Americans don’t have access to a photocopier and, therefore, couldn’t possibly prove under voting laws who they were. So, that’s just a very straightforward issue, which is proving who you are. Proving who your ancestors were, what’s the idea? A great 23-and-me test of all Americans or black Americans? What do you do when you discover that people are descended from slave owners and slaves?

Helen Dale:

Which is very common.

Douglas Murray:

The slave trade was sourced, but the organizers of it at the very root were, of course, black Africans, who continued slaving into the current era and still do today in some cases in countries like Sudan. But what would you do? Would that person get half of the millions awarded to somebody who was fully descended from slaves? Why should a Vietnamese-American who arrived in the 1970s, say, be paying money to somebody whose ancestors were provably wronged 150 years ago? This is an impossible conundrum, and one of the reasons I raise it is not simply to dismiss it; I want to take the claim seriously and look at it-

Helen Dale:

Well, you discussed the Israeli case in your book. I only bothered to look further because the Israeli case is in The War on the West.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, so I want to look at it seriously. I think, however, one of the conclusions that I’ve come to is that the people who are playing around with the reparations thing clearly don’t actually take it seriously themselves with the reparations thing clearly don’t actually take it seriously, themselves. As Gavin Newsom showed by effectively distancing himself from the conclusions of the committee of inquiry that he set up, it is impossible to imagine. So certain politicians, principally of the left in America and elsewhere, talk about reparations as if throwing a bone to the electorate and know, cynically know, that what they are discussing and playing around with is utterly impossible.

And I think that there’s something quite wicked in that because you are telling a portion of the public, some of whom won’t know better and will trust their politicians, that if they just hang around there might be a huge payday coming their way in a few years.

Helen Dale:

The money fairy will come.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah. And what will that do long term other than to store up a new type of resentment among a certain type of person, who will think, “I was told that the reparations were coming, I was sitting around waiting for them, and now they’re not, and how dare you keep my money from me,” will be the logical conclusion?

Helen Dale:

I personally think that the administrative difficulties with this is the silver bullet argument. But these people really, I’ve noticed this across the whole of wokery, because they discount the past, the past has nothing to teach us, and there is no information from the future, they really do think that anything is possible, that you can fly to the moon by flapping your arms, basically.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah.

Helen Dale:

So maybe I’m being too loyal by saying this is not possible; you are never going to be able to do this. Look at what happened in Israel. And there does seem to be, I did notice, Coates mentioned it in a couple of places, but there does seem to be no willingness to reckon with just how difficult it has been for the German and Israeli governments to do this properly, even when you had named known people, sometimes tracked down by the expedient of a set of numbers on their arm.

Douglas Murray:

And if you want to know long-term where this can go, consider something like… Look, when Greek politics goes wrong or when the Greek economy crashes, what is one of the go-to things that populist politicians of left and right, not a term I generally like to use, but for shorthand on this occasion, the populist politicians have left and right immediately go to? It is Germany owes us money for-

Helen Dale:

Yes, for the occupation of Greece.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah. So whenever the Greeks crash their economy, there’s always this thing held out, that maybe we can get the Germans to pay for it, because of the 1940s.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

And again, I see no likelihood, that, although in certain ways, funnily enough, the German economy does end up having to bail out Mediterranean Europe on a semi-regular basis. Nevertheless, I see no likelihood of a funds transfer from Berlin to Athens. But what is this? It is a hopeless thing dangled in front of people and an expression of resentment.

Well, resentment like that is not a healthy thing to encourage among the public, let alone… And it’s the line I lift from Nietzsche with credit. But what we’re really seeing in the reparations argument now is what Nietzsche refers to, is people tearing at wounds long since healed and then crying about their hurt. I’m not saying that the wounds of slavery have been utterly healed, but they are considerably closed—certainly more so than they were in the 1860s, say.

Helen Dale:

And more so than Israelis were confronting in, say, the 50s or 60s.

Douglas Murray:

Absolutely, when everybody lived with the knowledge and the experience of what had just happened. I think one of the go-to bits of wisdom in our area is that we should be suspicious of people who are trying to open up wounds that were otherwise closing. And that’s not to say we should be blithe about the past, or cover anything over. Far from it. I want as much historical inquiry and knowledge as possible, but we should be suspicious of the people who want things to have been worse, present things as worse today, and present solutions that are impossible to imagine.

Helen Dale:

Which are just impossible. I admit I have the lawyers’ thing here. There comes a time where you have to draw a line under it, that this is why statutes of limitation exist, this is why Res judicata exist, because if you don’t put it to bed, that is how historically, and we’ve got the Roman Juris writing about this, you finish up with cycles of vendetta. If you don’t put something to bed, that’s how you actually finish up with inherited duties of vengeance, banes, vendettas, and problems that have existed in Italy since antiquity with vendetta.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah. Yeah.

Helen Dale:

It’s interesting that you mentioned Nietzsche, because I think that’s a good bridge to the next thing I want to ask, because I think it’s salient here. I noticed in your gratitude section, you drew on some of Nietzsche’s arguments about the dangers of ressentiment.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah.

Helen Dale:

I’d be grateful if you could just adumbrate those for Liberty Law Talk listeners because not everybody reads Nietzsche, but I thought that was the best section of the book, I’ll be quite frank, and I just would like to hear you summarize it in your own words for us all.

Douglas Murray:

That’s very kind. I’m terribly conscious when I write books that it’s not enough to simply present a problem, but you’ve also got to try to present some answers, and that they have to be answers that are of an equal depth to the problem that you are analyzing. Nietzsche is, of course, one of the great philosophers, and also a philosopher who has to be treated with great care.

Helen Dale:

Yes, agreed.

Douglas Murray:

He is dynamite. He really is dynamite. His insights are unparalleled. But you’ve got to pick your way carefully through him. Badly read Nietzsche, you might even argue fully read Nietzsche, can be a very dangerous thing. But some of the insights are serum and ressentiment, let’s say there is a difference between ressentiment, as Nietzsche uses it, and resentment. Let’s not get into that. Let’s just call it resentment, so that we simply don’t sound like we’re trying to be poncy and French.

Resentment, Nietzsche analyzes the person of resentment. And the person of resentment is a person who has an explanation for everything that has gone wrong in their lives. And the explanation is everything other than themselves. It’s any outside force. It could be another person. I suspect everyone listening has at some point met a person of resentment, a resentful person.

The interesting thing about resentful people is they can come from every imaginable race, background class, and economic strata. As you probably know, Helen, we can all think of people who are extremely materially well off and seem to be enormously resentful people. I think we can probably also think of people in our lives who have very little in worldly terms, who are very non-resentful people, who are people who approach the world with great grace, and who receive grace in turn.

I use a section of Nietzsche’s work on the Genealogy of Morals because he explains that there’s only one way to knock the person of resentment out of the life of resentment. And that is for somebody, and Nietzsche doesn’t know exactly who, he says, a secular priest, which is an interesting idea. But he says somebody needs to stand over the life of the person of resentment and say, “There is somebody who’s ruined your life entire. The person is you.” Of course, that’s the last thing that anyone who’s resentful wishes to hear.

Helen Dale:

And it’s not something that… because so much of this is wrapped up with a self-diagnosed sense of mental illness, it’s not something that someone, whether they are mentally ill or not, wants to hear that, that, “No, I’m sorry. You are responsible for yourself.” It’s awfully Norman Talbot, “Get on your bike.”

There is a natural human instinct to wish to tear things up. In our own age, it can be heard in the sort of chants like, “Burn it down,” that can be heard as sort of anarchist and other marches. And I always say it can only be said by people who’ve grown up in enormous privilege, in the privilege of peace, and in the privilege of security and laws.

Douglas Murray:

Yes. Well, it’s to say that you’d have to start again, among other things. You’d have to start your world over again, and get back to the root of the problem and try to address it, which can be done. But the interesting thing, I think, in Nietzsche’s observation—it’s not just that, but it’s the observation that the only thing that can counter resentment as a force, that can knock it out, as it were, to think in Star Wars laser beam-like terms, is gratitude, that resentment, the only antidote, the best antidote to resentment is gratitude. And what does that look like?

Well, in the simplest terms, I can get up in the morning, and I can resent the things I do not have, and the things I do not have are legion; for me, as for every other person in the world, there is so much that we don’t have. And you can approach your entire day, and indeed an entire life, in that light. And you can find people to blame for it. My sister was always favored by my parents, and that’s why I don’t, and so on. All sorts of versions of this.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

And equally, you can get up in the morning and think of all the things you have. And the funny thing is, of course, that although this is a very straightforward bit of wisdom, it’s one you do have to be reminded of.

Helen Dale:

And you have to work at it too.

Douglas Murray:

You have to work at it. You and I are fortunate enough to have grown up in societies with civil order, for instance. I’ve been in plenty of countries, war zones where there is no such order. So I have a special appreciation, for the simple fact that if something is done to me in the street, someone who is paid by the state will try to help rectify that, and stop it, and so on. You can’t just go around beating people with sticks. That’s not to be taken for granted, now or historically. We have a system of law. Again, unless you’ve seen a country where law has broken down or is totally corrupted, to live in a laws-based system is simply one of the greatest blessings that you can have.

Helen Dale:

I’ve often had to quote significant jurists, judges, sometimes from court judgments, sometimes writing extra-judicially, sometimes operating in the Roman style, juristic style, going back to antiquity, pointing out that the most important thing in the world is actually order and everything else flows from that, because if you don’t have order, what you have is chaos. Not anarchy, but chaos, which is actually worse, because people constantly take everything into their own hands and administer everything by their own lights of justice. And I’m para… The Roman lawyers listening will realize I’m paraphrasing.

Ulpian goes on, a great Roman jurist, goes on a big anti-self-help rant, trying to get people all over the empire, not just in Italy itself, where it was well established, “You must go to the police. You must make a report. You must let the state do this. You must let the state bring people to court. It is not your job. You are not that person,” because people have to be trained out of taking vengeance. It’s very natural.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, absolutely. And I’d add that there is a natural human instinct to wish to tear things up. In our own age, it can be heard in the sort of chants like, “Burn it down,” that can be heard as sort of anarchist and other marches.

Helen Dale:

It’s really nasty.

Douglas Murray:

It’s very nasty. And I always say it can only be said by people who’ve grown up in enormous privilege, in the privilege of peace, and in the privilege of security and laws.

Helen Dale:

They don’t know what the alternative is like.

Douglas Murray:

They don’t have any idea of what the alternative is. And if law and order were to break down in their society, it would be first up against the wall. One of the things I think that often makes great writers and great political theorists is that they have seen into the abyss of what the alternatives are. And certainly, the writers I most admire—the obvious one is Edmund Burke—who saw what happened in France, and saw, with great terror, what was going to come next, including the terror.

Helen Dale:

Including the terror. Exactly. Precisely.

Douglas Murray:

You might say Montaigne was fortunate enough… I say fortunate enough, it wasn’t fortunate at the time, but to have lived through the wars of religion, and to have seen to the extremes of barbarity that people were willing to go to in the name of faith, and their perception of God, and to have seen the breakdown that the wars of religion caused in the Europe of his day.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

Was to come out the other side with an enormous admiration for order, including the absolute centrality of legal order.

Helen Dale:

Because one of the things that got me after I retired from full-time practice at the end of 2016, that got me into this debate, and instead of just writing novels and fiction of various kinds, or writing book reviews of other novels, which is what I’d always done historically, was what appeared to me to be a concerted attack on the rule of law. And from Ulpian onwards, people have generally divided the rule of law into eight different heads, and it all gets a bit complicated. And that’s worth reading. It’s in Hayek, it’s in Raz, it’s in Ulpian, and it’s worth the read.

But the basic principle of the rule of law, that you can distill it all down into one, is to treat like cases alike. And all of this race betting that says you should treat someone differently in terms of the opportunities you give them, or in terms of the way you treat them interpersonally, and so on and so forth, are based on smashing up that core legal principle of treat like cases alike.

Douglas Murray:

Yes. And I would add that I give some examples in The War on the West, but I would add that there are those who say today the system of law is white, that the laws are white. And there is so much danger in that, as well as a simple inability to recognize precisely what you just said, which is a law that is set up in our countries. It is fortunate in being blind, that justice is, when put in statute form, literally blinded, and that is the system we are fortunate enough to have.

To turn that into a system that is, like everything else, accused of being institutionally racist, or based in whiteness, is to pretend that the law as we have it, and enjoy it, should not be enjoyed by non-white people and that some other system of justice should occur with them. The people who make these claims cannot have thought… Like the people who say burn it down, cannot possibly have thought about the consequences of their own claims. And they never seem to think even one chess move ahead, you know?

Helen Dale:

They see the living embodiment of… This is a quip that is often said among lawyers and is probably known elsewhere, but I first heard it from my pupil master when I was a baby barrister, and he used to say when something like this tended to happen, people hadn’t thought their thoughts through to the end basically, with a piece of legislation. He used to say, “This is a reminder, Helen, and always remember this, that the only law all this enforce is the law of unintended consequences.”

Douglas Murray:

Yes.

Helen Dale:

And it stings, but it’s true.

Douglas Murray:

It’s a very wise observation.

Helen Dale:

Just on the Nietzsche point again, because that chapter was so moving and it really did make me think, and I did that thing of going out and cycling around the neighborhood and just thinking about some of the ideas that you’d raised, because Nietzsche talks about a lot of issues in Genealogy of Morals, and that’s where all of… It’s just for listeners; that’s where all of this is coming from. Some of those concern… He has particular views on people being victims, on the idea of victimhood.

Now I’m going to say… I’ll just throat clear and disclose here. I’m asking about this, what insights may come from his perceptions and discussions of victimhood because the most substantive Roman criticisms of early Christianity concerned its valorization of victimhood.

Douglas Murray:

Yes. Yes, yes.

Helen Dale:

Now there are lots of other Roman criticisms. Many of them are very silly, like, “oh, they’re cannibals because of the Communion” and that kind of thing.

Douglas Murray:

Sure.

Helen Dale:

Many of them are very silly. This one is not silly. And basically, the way various Roman jurists and Roman writers put it was the idea that victims… This religion, they will say, this superstition, superstitious claims that victims have something to tell us by virtue of their victimhood. This appears in its clearest form in a writer called Celsus in the second century AD, and Nietzsche revisits a lot of Celsus.

And when I was a classics undergraduate, an academic had actually written a paper comparing phrases in Celsus with phrases in Nietzsche. And I have to say, it did get a bit tedious after a while. It was like he’d run Celsus and Genealogy of Morals through Turn It In and then pulled out all the red highlights. But the point was a fair one. Is there something still in that… It’s not Nietzschean in this case, it’s a Roman insight. And if so, what should we do with it?

Douglas Murray:

Yes, a Roman insight, that certainly Nietzsche left, but Nietzsche is, of course, an anti-Christian philosopher, but that’s one of the many reasons why I say you have to pick your way through him with great care. The observation on… It’s really Nietzsche’s principal objection to the Christian ethos is exactly to say it’s the valorization of suffering. There is a lot to that. I would say it’s simply an example of the fact that everything can go too far. As I always say, absolutely everything in the world, including all virtues, can be corrupted by being led to including all virtues can be corrupted by being led to extremes.

I mean, I regard the Christian insights on suffering, the Christian theology on suffering, as being among the most profound contributions that Christianity gives to the world. I think from it, we get many of our current perceptions about rights and about the dignity of individuals and our sympathy for individuals who have fallen on hard times, and much more. I don’t say any of this lightly because, again, there are societies in the world, and there are ethical systems elsewhere in the world which do not regard people who are unfortunate as being deserving of sympathy or support, for instance. Belief systems that believe in reincarnation, for instance, very often believe that the person who is on the street begging does not deserve alms because they did something in a previous life that has caused them to be in this situation, and to help them in any way would be to actually harm the system of justice that is occurring.

Helen Dale:

This is a sort of cosmic justice. I saw this in Cambodia, actually. People who’d had their feet blown off by standing on Khmer Rouge landmines were not treated with a great deal of sympathy because the argument was that in a previous life, they’d done something bad, and so that’s why their foot had been blown off by standing on a mine.

Douglas Murray:

Can you imagine being a person in that position? I mean a double whammy from fate, to both wound you and then wound you again. So Christianity does produce this extremely important ethos of compassion and an ethic around suffering. I would argue that it is true that some wisdom can come from suffering. It’s just that it’s not inevitable, and it isn’t limitless. For instance, who, when … And I’m making this rather trivial, but I hope it isn’t. Who, when they have suffered a blow in their lives, does not approach the people they come across that day in a spirit of greater charity and kindness? If something terrible has happened to you in a day, you might see the unfortunate person begging on the pavement in a kindlier light. You might not pass some of them as easily or as willingly. You might even do something to help.

My observation is simply that suffering does, to an extent, remind us of the fact that we are all mortal, we’re all capable of falling from high to low, and that affliction afflicts us all. However, there is a perversion of the ethic of suffering, which is that simply by the nature of having suffered something, wisdom must naturally accrue from it.

Helen Dale:

That’s what Celsus was arguing against. He thought that was nonsense.

Douglas Murray:

And it’s a point that’s been made by certain people in our own day. There’s a right of the political left who’s a friend of mine in Britain who observed many years ago that, actually, this is one of the problems of the contemporary left, is that it thinks of, for instance, people who have suffered as inevitably behaving well if the suffering is stopped. If you live under a dictator and you suffered under a dictator, if the dictator is removed, the people will be good. Unfortunately, this time and again is shown not to be the case. You can suffer and be bad.

Helen Dale:

Or be nothing. That’s the other thing. I had Celsus’ line about, just because you have suffered or because you have been sentenced, because, of course, he’s arguing with Christians, Celsus was, and Jesus had been executed for a public order offense. Romans didn’t like public order offenses. He’s saying just because someone has gone to jail or someone has been executed, that doesn’t mean they necessarily have any insights for the rest of us. And as I was riding around the neighborhood thinking about that chapter, the George Floyd thing came to me. A Roman would’ve been horrified by a citizen, not so much a non-citizen, certainly a citizen being killed by a policeman. And the policeman would’ve been in a lot of trouble, and a legionary would’ve been cached. This was not something you did. So isn’t it enough that the policeman was tried and convicted and sent to jail for murder? This is how Roman jurors would look at it. You don’t have to pretend that George Floyd is some sort of marvelous person. That was what came to me.

Douglas Murray:

Absolutely. I mean, I agree. I mean, it is the perversity in the ethic of our time, this, epitomized, if I can say so, by Nancy Pelosi coming out with some fellow senators after the trial of the policeman who killed George Floyd. She came out on the steps of the Senate and looked up in the air, and she said, “Thank you, George Floyd. Thank you for giving your life for justice.”

Helen Dale:

I didn’t know that. I don’t follow American politics. Oh my Lord.

Douglas Murray:

I mean, I don’t think that George Floyd set out that morning to improve the life of the average American by giving his life. I mean, this is a perverted form of watered or spilled Christian ethics and much more spilling into our time. And there’s a lot to criticize in that. There’s something to be said for it. I mean, it has to be said, which is on this particular occasion, people trying to ameliorate the wound being felt by Black Americans who feel that there is an injustice in the way in which they’re treated by the police. I think that probably what happened was that people overdid it for fear that Black Americans and others might overreact themselves in response to this terrible event, but my own view is that it’s almost always unwise to interpret an entire society through the lens of one horrific act.

And that that is, to an extent, what has been happening and has been happening with a very free run in America and the rest of the West in recent times. I mean, if I can give one very quick other example, one that not many other people have lingered over, although I see the Canadian writer Jonathan Kay has recently, is that a couple of years ago, there was a moral panic in Canada when it was claimed that the bodies of Indigenous children, the graves of Indigenous children had been found by a Catholic school in Canada. And the implication was this was a mass grave and that the children had been killed somehow by the Catholic school because they were Indigenous. This was a sort of genocide and just-

Helen Dale:

Not allowed to die or just died of disease or?

Douglas Murray:

It wasn’t made clear. But every innuendo was possible. And this became very real, very fast because people started burning down churches in Canada.

Helen Dale:

Oh, I remember this, yeah.

Douglas Murray:

Including Indigenous wood-built churches, which will not be replaced. And even people who were close to the Prime Minister of Canada started doing sort of burn it down. To this day, not one grave has been uncovered.

Helen Dale:

My understanding from what you said in the book, I mean, I don’t know whether the news cycle has moved on, but I understand from what you said in The War on the West is it was almost as if they were reaching for a similar history as to what’s happened in Ireland with the industrial schools and the maudlin asylums. And even there, it’s been exaggerated, but not to the same degree. And there’s nothing. It’s a big fat zero, nada.

Douglas Murray:

No. They said they were going to do an ultrasound on the ground.

Helen Dale:

Ground penetrating radar is what archeologists do, yes.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah, and there’s nothing there. This is a very interesting perversity of our time, as you say, Helen. I mean, partly, it’s wanting their own version of the American racial history imposed upon itself.

Helen Dale:

Or what happened with the church in Ireland, which really was an extraordinary scandal.

Douglas Murray:

There’s a very successful new book published by a British author recently. It’s called, This is Not America. It’s saying, let’s not impose American racial politics on Britain. But that is something that people have been doing with great abandon recently, which is combined with another interesting trait in our time, which is to try to think the worst of ourselves. It’s very understandable to want to think the best of yourselves as a society. It’s a very strange, I think, rather modern phenomenon to wish to think the worst of yourselves. So that instead of saying, “Well, hang on a moment. Let’s just see if there is any evidence of the mass killing or mass graves before getting all burning about things,” I think one of the reasons why the Canadian media has not revisited this panic is because, A, they’re probably embarrassed.

Helen Dale:

Oh gosh, yes.

Douglas Murray:

And B, they wanted it to be the case. They would rather that mass graves were discovered than that they weren’t. And I’m not being flippant in that. I genuinely-

Helen Dale:

No, no, I’ve seen this. This has happened in Australia as well. There’s been an exaggeration of what has been done, which was bad.

Douglas Murray:

Yes.

Helen Dale:

Exaggeration of what has been done historically to the Australian Aborigines. And people have then very carefully investigated; anthropologists and archeologists go and investigate it, sometimes government commissions, and find out that it wasn’t as bad. And that’s never reported with the same fanfare as afterward.

Douglas Murray:

No, absolutely.

Helen Dale:

It’s less bad in Canada. You don’t have the same nonsense in Australia as you do in Canada. But that trait, that element, is already present.

Douglas Murray:

I mean, I wrote about this a bit in The Strange Death of Europe, but I said this in the Australian context, that it’s very interesting that in our own lifetimes, the happy country has been turned into a darkened country, a slightly polluted country. I think this is a very interesting turnaround in our time. And it’s happened … I mean, the point I’d make in The War on the West is the way this has been done with American history, most obviously, where, I mean, I give the example of some of the great figures of American founding like Thomas Jefferson. People positively want Jefferson to be seen in a negative light.

I, a little while ago, spoke at one of the great institutions alongside the United States Thomas Jefferson set up, which is the University of Virginia. As I mentioned in my remarks there, the fact that actually, the DNA evidence that suggests that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemmings’ children is not conclusive. There is a Jefferson gene in the Hemmings family genes, but it does not mean that Thomas Jefferson raped his slave. However, some people were absolutely insistent about this and that it can’t have been a relative of his. It must be of Thomas Jefferson himself.

And it was quite amusing to me that after my remarks, a woman in the audience came over to me positively furious that I had said that Thomas Jefferson might not be a rapist. And I said to her, “It’s very interesting because 100 years ago, if I’d have spoken at UVA and said that Thomas Jefferson was a rapist, I’d have had people who are furious with me. Today, you’re furious if he isn’t a rapist.” That is an odd position to be in. I understand the former more than I do the latter. I understand people’s desires to think well of themselves and their country’s history. I think it is a rather baffling perversity of the modern age that people wish to look as negatively as possible at their past and to be positively furious if there’s anything good in it.

Helen Dale:

The former Australian Prime Minister, who’s still alive, used to describe this. He had a good expression for it. I think he would be very happy if you stole it and propagated it widely.

Douglas Murray:

Is it John Howard?

Helen Dale:

Yes, John Howard. He called it the black armband view of history. And when he used the phrase, he used to stand up and say, “This is the black armband view of history.” And for listers, I’m wrapping my hand around my opposite shoulder and upper arm, black armband.

Douglas Murray:

He’s good.

Helen Dale:

Yes. That’s John Howards.

Douglas Murray:

Yes. That is very good.

Helen Dale:

Yes. The black armband view of history, he used to call it. Steal that from him and propagate it outside Australia.

Douglas Murray:

I will do. I will do. Well, of course, as I said, I mean much of the thinking on this has come from Australians who noticed this happening because it happened so swiftly in Australia.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

It’s happened relatively slowly in America by comparison.

Helen Dale:

It took longer to try to argue that their founders had feet of clay, yes. Partly because their founders, I mean, some of Australia’s founders, were a bit equivocal. Genuine mixtures of good and bad, that is. The country became better and more orderly and arguably better governed than the United States over a process of history. It didn’t have these stars at the beginning. I mean, Alfred Deacon is not George Washington. He was a very capable and able Prime Minister and an interesting character, but he was not Washington or Jefferson and did not write like either of those men or anything like that. So it had a very different history, and of course, a very equivocal start because it started as a penal colony.

To turn away from The War on the West at the moment, which we’ve hashed over quite a bit of it, and just to step back and broaden out a little bit, you were a speaker at the National Conservatism Conference in the UK, and I saw your talk at the Natural History Museum. I just thought for American listeners who may be familiar with the US version of the National Conservatism Conference, it might be just worth asking you—what was your general impression of the UK National Conservatism Conference, and where do you think it goes from here?

I think that if one group of people have the right to a national identity and national belonging, then everybody really has to. You can’t say only some people have that right and others don’t….But I say that at the same time as saying, I would not want to encourage a nationalist movement in Germany.

Douglas Murray:

As I’ve said to Yoram Hazony, who’s the founder of the National Conservatism Movement, distinguished Israeli thinker, and philosopher, as I’ve said to him, I’m two-thirds in agreement with the National Conservatism platform. But nevertheless, yes, I spoke at the recent London event. I’ve spoken before at their events in Rome and in Florida. I didn’t attend enough of the Conference, but I’ve watched quite a lot of it since and a lot of friends were speakers at the Conference. I think, and I’ve said this to Yoram myself, that one of the interesting things about the term nationalism is that it is like liberalism. It’s a shape-shifter term.

Helen Dale:

Lord Frost says the same thing.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah. It changes meaning as it crosses borders. I mean, for instance, nationalism in the Israeli context is one thing, something I happen to think is a good thing. The Israeli state would not exist without Israeli nationalism. I think that in America, it is relatively easy to talk about movement. In Europe, it becomes extremely difficult. I mean, let me give you a couple of examples. For instance, if you say British nationalism in Britain, people immediately think of the British National Party, which was a far-right party, which is now defunct, run by a horrible man who was actually a Nazi apologist and much else. So if you just said British nationalism in the British context, you would alarm people because they would think of the far-right movement.

Now, however, if you say Scottish nationalism.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

I mean, there is a Scottish Nationalist Party called the SNP. They are in government in Scotland.

Helen Dale:

Not very happily, admittedly, at the moment, but.

Douglas Murray:

Not very happily, and not a party I adore, but the SNP is not regarded as far-right. Take it to Ireland and Irish nationalism is a very complex thing, but it is not regarded as a far-right movement. Go to Germany and try German nationalism. That’s a different thing. The same thing in Italy. It’s very difficult. Italy’s very complex. Spain. I mean, the point is simply that Europe is always very, very complex. We have had such a well-recorded and difficult history. We had the wars of religion, we had the wars of nation-states. We had the disastrous wars of the ideologies, the twin horror ideologies of the 20th century of fascism and communism. We’ve had all of this in Europe. So as I’ve often said, 20th-century Europe, in particular, still sits behind crime scene tape. People are still trying to work out how on earth it happened.

I mean, that’s why a lot of the philosophy of Europe, some of the culture of Europe, even is effectively behind the crime scene tape still. Because the question remains, how did it happen? How did Europe do this? How did the most civilized societies on earth, the most cultured societies on earth, and how did a city like Vienna turn from what it was in 1902, the cultural centerpiece of the world, into what Vienna was in the 1940s and what it allowed, what it encouraged? So this makes everything to do with the term nationalism just incredibly difficult. I think it needs to be decomplexified to some extent. We need to work out what is and what is not legitimate. I think that if one group of people have the right to a national identity and national belonging, then everybody really has to. You can’t say only some people have that right and others don’t, and one country has and one country doesn’t. But I say that at the same time as saying, I would not want to encourage a nationalist movement in Germany.

Helen Dale:

No, I still think that’s fraught with danger, even though the Germans appear to have gone completely soft and squishy. My partner has this expression that particularly in the early days of the Ukraine war where Germany was useless, but Germany went from being-

Douglas Murray:

Oh, yeah.

Helen Dale:

… terrifying to a kind of joke.

Douglas Murray:

Well, the one thing that the Germans still do is believe that they should direct the moral course of history. It’s just that they do it in a different light today.

Helen Dale:

Yes.

Douglas Murray:

I mean, they try to encourage the rest of Europe to be like them. And it’s much more desirable. I mean, it’s not desirable. It’s a much more desirable ethic than the ones they tried to force Europe into in the past. But nevertheless, there is this strange, endless German presumption that what Germany does is what Europe should do.

Helen Dale:

Yes. It’s fueled, of course, by the power of the German economy, which is still significant, even allowing for all the problems since the war in Ukraine. The ability to speak out and disagree was what used to be called political correctness. I’m showing my age. I worked out that I think I’m six or seven years older than you, so it was political correctness when I went to university. These days it’s called woke. Is, to some people, severely curtailed. People really do get sacked for questioning DEI training days at work, like Jody Shaw at Smith College. She really did get sacked for questioning DEI training days at work.

Helen Dale:

She did get sacked for questioning DEI training days at work. It’s not just her. This is a very common story. You just happen to flag her up in the book. People get sacked for saying the wrong thing on social media. People get sacked for telling a joke that doesn’t land with everyone else in the tearoom. A genuine privilege both you and I share is freedom of speech without our jobs being placed under threat. What should Joe and Josephine average do? What can they do?

Douglas Murray:

It’s a question I think about a lot, and you are right, Helen. You and I are, and we should confess our privilege in the-

Helen Dale:

Oh it is, absolutely.

Douglas Murray:

… of being able to say what we think, and it’s also a pleasure. I think that everyone who has that privilege should use it and try to make it easier for everybody else. I believe that, as you say, cases of people are very often dismissed by people as being sort of right-wing talking points; they’re really not. You can be a librarian at a college, or you can be a partner at KPMG, for instance, who was fired after saying that he thought that implicit bias training was a crock.

Helen Dale:

That’s what he said. Very Australian. And it’s true, it is a crock.

Douglas Murray:

It’s true. And he lost his job because junior employees said they weren’t happy with him, saying that he thought that implicit bias for anyone was a waste of everyone’s time. So you can be a person of considerable power and influence and lose it all. Or you can be somebody of really relatively little power and influence and lose it all. My suggestion is always when I’m asked this, I don’t like to encourage acts of kamikaze like bravery. I would like everyone to be braver, but I know that people, particularly young people starting off in their careers, they don’t want to implode immediately. What I do suggest is that everyone should just be a little bit braver and speak up a little more.

So, you see, if in the case you cited earlier, we were talking about earlier of if somebody says something that’s sort of anti-white racist or generalizing about white people would be just to say, “Oh, that doesn’t land well.” Would that be good if you said that about other groups? Do you say that about other racial groups? I hope not. I say that if people are given reading lists by colleagues or let alone bosses, they should say, “Oh, I’ve got some books that you should read. I’ll read your books; you read mine.” If they say, “No.” Oh, that’s not a free exchange of ideas, then, is it? It’s me being expected to listen to a sermon. Is that in the deal? Is that in the contract?

Helen Dale:

That’s right.

Douglas Murray:

I think there are a lot of things that people can do that are not totally destructive to them or wouldn’t be totally destructive to them and which could just encourage people a little bit more. I feel very sorry for… I think the worst are people who know that what they’re doing is wrong and nevertheless go along with it out of weakness. I say that’s the worst because people who do that grow to hate themselves. Because it’s one thing to be a bit cowardly, it’s another thing to know that you are a coward, and that eats away at a person, actually. It makes you realize, makes you think you’re nothing because you’re not far away from it, actually. To be and to not identify the truth as you see it or let alone the truth as it is, and to remain silent is a profoundly demoralizing experience, which I encourage people not to go through. They don’t have to put themselves through it.

Helen Dale:

Try if you can in those circumstances to fight back, or you do finish up. The hollow man with the headpiece filled with straw. There’s nothing left.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah, it’s a very sad position to be in, and people should… Because the best advice on what to be in your life is to imagine what it is you would like to be and to get as close as possible to that. What I’ve just described is the opposite. To see a cringing, embarrassed person who hates themselves.

Helen Dale:

The other thing, and this is partly a crowdsourced question that’s come from family members. There are quite a decent number of people, particularly in the part of the world where I live, which is sort of the classic home county’s Tory Shires. They’re like my partner, also retired from a job in the city, who don’t have public profiles. So they’re not like you or me, but they do have the expertise and the financial freedom to speak or to do something. So my partner very much falls into this category. How can they help push back against the tide? What can they do? I know I’ve got now king commute symbols going on there, but how can they help push back or fight back? What are good strategies for them to pursue? Because I do think there’s something that there’s work to do for people who aren’t public figures in any way but also can’t be harmed because they are financially secure.

Douglas Murray:

Yes, financial security in this era does matter enormously. It’s one of the reasons why the people I actually loathe the most, if I treat myself to a bit of loathing, are the people with F you money who don’t say F you.

Helen Dale:

Yes, I agree. Because whilst I don’t have F you money, my partner and I have a considerable amount, and I’m quite happy to get up and say F you and do so regularly, usually more politely than that. But yes.

Douglas Murray:

Can you imagine if we’re sort of Bill Gates rich and were still able to be intimidated by you and your employees? But people who are secure, I think, are what I described as the adults who are most missing from the room. There’s something very strange about a society in which the adults pipe down because it suggests that we put no premium whatsoever on experience or wisdom. We put a premium only on youth and ignorance. I’m not saying that all young people are ignorant, but you’re more ignorant at the age of 20 than you are at the age of 40 than you are at the age of 60. It’s a very curious society, and by no means common throughout history for a society to only listen to those who know the least. So my own view is that people who are older and secure financially should in every way they can say, “Excuse me, but I know something too.” They should say that in their lives, they should say that to people they encounter. They should say it to institutions they’re involved with.

They should lead a counter-movement that doesn’t need to have its own aims other than to say, “We don’t want this crap thrown in our way.” For instance, I think that the people who are secure in society should point out the actual terrible things that are going on, which we are being distracted from noticing. For instance, it is with almost 100% certainty that I can predict which school districts fail the most in America. It is the districts that talk about historical injustice, that talk about grand strategies to uproot white supremacy. You can tell that a teaching union is failing when it starts to talk about these grandiose things that are not in its purview. Why do I say that? Because with almost 100% certainty, you can check the reading levels, the literacy levels, the attainment of math, and particularly among minority students and particularly among young black students. You will notice that these are the bases with the lowest attainment levels. You have areas I visited in the US where 7% of Black children leave school with a math or language literacy.

Helen Dale:

Oh, pitiful.

Douglas Murray:

That is just shocking. Absolutely.

Helen Dale:

That’s worse than the worst parts of Glasgow. Much worse. The SNP hasn’t exactly been a fabulous government for Scottish education, but that is much, much worse than the worst districts in Glasgow. I’m sorry, I used to work in the Scottish Parliament, so I’m sort of familiar with the issues there.

Douglas Murray:

Yeah, well exactly. It’s a very pertinent example because wherever you set up a grandiose explanation, a totalistic explanation for everything that’s going wrong, in the case of Scottish nationalists, it’s if only we were independent. If only we didn’t have Westminster ruling over us. This is meant to explain everything. Look under the bonnet, and you see they can’t run the health service; they can’t run the schools, the Scottish education system that actually used to be a jewel.

Helen Dale:

Oh, it was a jewel in the crown, but it’s still not as bad as those American figures. But it did use to be England compared unfavorably with Scotland. I actually lived in Scotland during the period of that transition, which was quite unpleasant as Scottish schools fell behind.

Douglas Murray:

But that’s because the Scottish nationals can always point to if only we were independent. It’s the same with teaching unions and the failing school districts in the United States. Always, if only we could solve this unsolvable issue from the past that is not in our gift to solve. You look under the bonnet, and you can guarantee they’re not doing the one thing they’re meant to do. So I think that’s a long way around. But I think that all those people who are in a position of security should be, among other things, drawing attention to such things, trying to rectify such problems, and making sure that, as societies, we don’t fall into these simplistic and self-harming interpretations of ourselves. Because it is almost guaranteed that those explanations will solve nothing because they don’t actually explain everything by any means.

Helen Dale:

It’s beyond that, which is good advice for people like my partner, who I think will listen to this very carefully. Just coming back, and some of this came up at the National Conservatism Conference, and there are elements of it then the last, the conclusion to The War on the West. More broadly, what sort of policy proposals do you have? Inevitably, this is a law-based podcast, so the lawyers are going to ask about policy because we care about this sort of thing because we are often the policymakers. What sort of policy proposals do you have that may help reverse the ideological capture of so many British institutions? I’ll confine it to Britain here because it is something I know better, at least.

Douglas Murray:

Well, in Britain, there’s a lot to be said; it differs from institution to institution. I simply think nothing in receipt of government funds or taxpayer funds; let’s say the government doesn’t earn the money. Nothing in receipt of taxpayer funds should be allowed to war on itself. Institutions are meant to exist to continue the legacy of the institution. They are not meant to war on the institution in question. So, for instance, if the trustees of the Tate, to use one example, that’s close to my heart.

Helen Dale:

Oh, the Whistler painting. Yes.

Douglas Murray:

And much more. Stanley Spencer, they’ve made an assault on their own collection. The trustees of the Tate are only in position because they are meant to preserve for the next generations one of the great national collections. If the trustees of the Tate decide instead that their job is to stand as judge, jury, and executioner on the reputations of the artists whose artworks they’re in possession of, they should receive no funding from the government or anyone else. Private funders can choose if they want to support this self-hating institution, absolutely. They have the right to do what they want with their money. But no taxpayer money should ever go to an institution of the state and of the nation, which believes that its job is to war on the institution in question. In other words, the people who are meant to be the custodians of the culture should be the custodians of the culture. They should not regard their job as being the judges of it, particularly not if they believe their job is to be the judges who judge it in the nastiest and most uncharitable light imaginable.

Helen Dale:

It’s just extraordinary the judging of the artist’s character, not their art.

Douglas Murray:

Well, wherever I go in the world, I always want to see the national and local collections anywhere. It is only in Western democracy that we end up in this bizarre position of self-hatred. If you go to one of the great collections like the National Museum in Cairo, you do not see the great collections from antiquity with big signs up saying, “You’ve got to remember that this was made by slaves and that there wasn’t equal pay distribution among the people who created this staff of Tutankhamun.” They don’t do this. They just say, “Here are wonderful things we have, which we are very proud of, which we show to the world.” There’s always a difference, I’m not holding that museum up as the totem of how to present museums of the world. But I’m just saying that is normal.

Helen Dale:

It is a lovely museum, though, yeah.

Douglas Murray:

So that’s the way you do think so that visitors to your country are shown the best of what you have—the idea that all your cultural institutions would be engaged in this weird act of self-harm. I was speaking recently to a friend at Harvard who said that Harvard University in the United States was talking recently of an inquiry, like so many institutions, into what reparations Harvard University might need to pay depending on Harvard’s benefiting from the slave trade. This person I was speaking to said they pointed to the huge memorial center of Harvard to the students and the graduates of that university who lost their life in the Civil War fighting against the armies of the South. This person I spoke to, said he pointed at this and said, “We’ve already paid.”

Helen Dale:

In blood.

Douglas Murray:

In blood. I think that the adults should say that sort of thing. We have a lot of know-nothings in our societies now who very often stumble upon our past as if it was a total secret. Here are the two. I think that the adults should say, “Excuse me, but we know about this too, and it’s possible we know more than you.” For instance, you talk about the slave trade, but what do you know about it historically or in the present? What do you know about what Britain did to abolish the slave trade? Again, it’s this light and dark thing you can learn about. You can learn about British involvement in the slave trade, which is unarguable.

And you can also learn that Britain led the world in abolishing this vile trade. You don’t need to teach only the good, but to teach only the bad is a very perverse thing. And to look at your collections and your history only in this negative light is far more perverse than looking at it only in a positive light and much more damaging. Why we cannot find some equilibrium here bemuses me. It can only be explained by the fact that our culture is dominated by very ignorant and cowardly people.

Helen Dale:

Yes. Anyway, we’ve been chatting for quite a while, and I don’t have a cool question to ask at the end, like the trigonometry lads. But I think they’ve patented the whole… What should we be talking about that we aren’t talking about? That’s just a brilliant killer end-of-interview question. I’m afraid I don’t have one of those. And because you’re not a lawyer, I can’t ask.

Douglas Murray:

I’m never prepared for that question.

Helen Dale:

Oh, no. Nor am I. I’ve been on twice now, and both times I completely footed myself. So it’s not just you. But what I will recommend to Liberty Law Talk listeners is to give The War on the West a read. It’s quite a quick read with lots of footnotes, so you can go exploring further as I did as I went down the Israeli reparation’s rabbit hole, which was very, very interesting to explore further. It’s also the video recordings for the UK National Conservatism Conference available on YouTube. You can watch them all, including Douglas’s talk that he actually gave at a supper. The reason it looks different from all the others is because the supper was held in the Natural History Museum, so it’s a very different-looking venue. Apart from that, is there anything else that you’d like to let people know about? Are you working on something else, or are you able to put out a bit of a teaser for our listeners?

Douglas Murray:

I’m always working on something else. I can never discuss what simply because I’m very wary of talking myself out of anything that I haven’t yet written down.

Helen Dale:

Fair enough.

Douglas Murray:

Good lesson for writers.

Helen Dale:

That’s a very good lesson for writers.

Douglas Murray:

I suppose I would also point them to, I write columns in the Sun, the New York Post and Spectator, and various other venues, National Review. I also, if people are interested in, as it were, an addendum to The War on the West, I did a set of interviews with academics called Uncanceled History, which is available free on YouTube. Ten interviews with leading academics on some of the most now contested figures in particularly American history. Christopher Columbus, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and so on. It was my great honor to speak with some of the great scholars of our time who are still around, and who actually know what they’re talking about. So yes, Uncanceled History is available free on YouTube, and there are 10 episodes. I’m very proud of the discussions and of the wisdom that I was able to tease out. Didn’t require much teasing, but a gain from these distinguished people I spoke with. So I’d much recommend that, yes.

Helen Dale:

Thank you very, very much. Thank you very much for coming along to talk to us at Liberty Law Talk, a project of Liberty Fund.

Douglas Murray:

It’s been a great pleasure, Helen. Thank you.

Brian Smith:

Thank you for listening to another episode of Liberty Law Talk. Be sure to follow us on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts.