“The Founders intended the Constitution to promote a way of life, and they understood that to promote a way of life is to promote a kind of person.”

Rethinking the "Danger" of Public Christianity

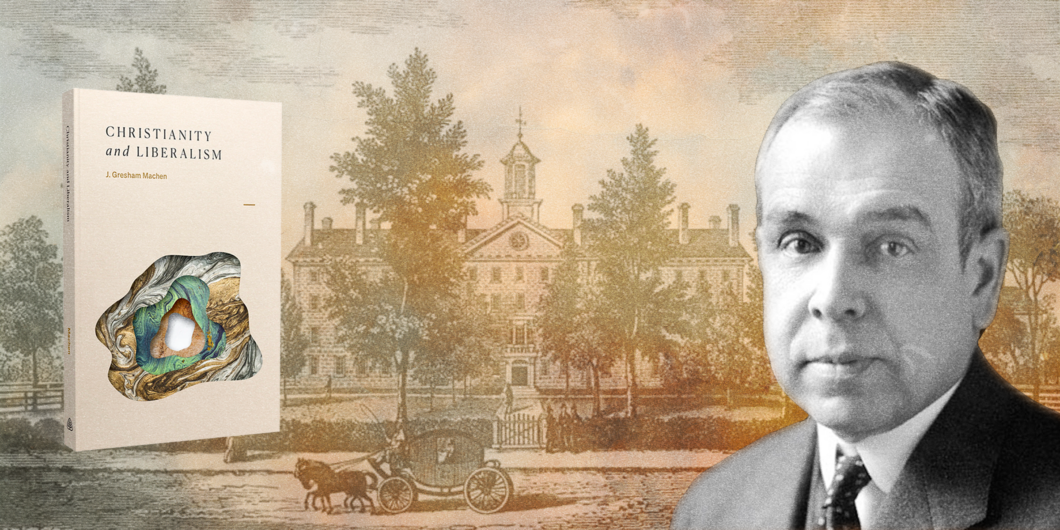

In 1923, a middle-aged professor of New Testament at Princeton Seminary, J. Gresham Machen, produced a book that asserted liberal Protestantism was not simply a defective version of Christianity but a different religion altogether. Talk about provocative. Was Machen trolling liberal Protestants? One hundred years later, white conservative Protestants in the US spent a good chunk of last year commemorating Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism. The reasons are not hard to imagine. Here was a student of the Bible who was fed up with what religious and political Progressivism was doing to American churches and society. Machen breached the manners and ethos of elite society to claim that America’s largest churches were Christian in name only. If today’s post-liberal Christian Nationalists wanted a historical figure to emulate in their own frustrations with contemporary America, Machen is an obvious candidate.

The problem is that the Princeton professor was several lanes removed from the idea that America was a Christian nation. His complaint about liberal Protestantism was mainly theological. He conceded that liberals had a point about the difficulty of science-following modern people believing in the miracles that came with the Bible. The virgin birth (a topic about which Machen wrote a lengthy book) and the resurrection of Christ were hard beliefs to maintain among college-educated Americans. The problem, as Machen pointed out, was that removing the supernatural parts of Jesus turned Christianity into a different religion. In the words of H. L. Mencken, who wrote a favorable obituary of Machen (who died in 1937), liberal Protestants had turned Christianity into effete “nursery rhymes,” a “series of sweet attitudes, possible to anyone not actually in jail for felony.”

As appealing as Machen may be to today’s Protestant conservatives, his politics do not provide support for those who want to replace John Locke with John Calvin. Machen was a lifelong Democrat from the Free State (Maryland) who landed in the states’ rights, small government wing of the Party’s coalition. Christianity and Liberalism tried to hook readers bored by church controversy by mentioning what Progressivism was doing to the United States. The rise of nationalism (or Americanism) after World War I was responsible for state legislation to restrict public school instruction in foreign languages. This was one example of the Progressive and ecumenical Protestant drive for a unified nation that turned cultural diversity into a peril. As such, Machen defended the liberal tradition of American government—in its federal, republican, and constitutional expressions—even while he opposed liberalism in theology. For some readers, such as Walter Lippmann, Machen’s strategy in framing the book—in defense of liberal politics, in opposition to liberal Christianity—was a success. In A Preface to Morals (1929), Lippmann judged Machen’s book to be the best argument produced by either side in the so-called fundamentalist controversy.

Machen was far removed from Christian Americanism and mocked Progressives for identifying the United States (understood here as a redeemer nation) with the Kingdom of God.

Today, Machen’s politics—a libertarian, small-government Democrat—do not map easily onto Blue-State-Red-State debates even while his theology and biblical scholarship still resonate among conservative Protestants. A wide diversity of Protestants, from Baptists to Lutherans, have run conferences, chosen themes for magazines, and recorded episodes of podcasts on Machen’s book. This is curious if only because when the book turned fifty and seventy-five, those magical anniversaries divisible by twenty-five, Protestants paid scant attention to Christianity and Liberalism. But today, readers have choices for which 100th anniversary edition to buy, the one published by the seminary Machen founded (Westminster) or the popular theological ministry, Ligonier. Perhaps World magazine’s naming Christianity and Liberalism the book of the year for 2023 gave Protestants room to commemorate Machen’s book.

Machen’s appeal to contemporary Protestants may have a significance that few have noticed. For all of the commentary, mixed with alarm, about blurring the lines of religion and American politics generally and the dangers of Christian nationalism specifically, the wide and diverse audience for Christianity and Liberalism shows that Protestant conservatives are motivated more by faith than by politics. Machen was far removed from Christian Americanism and mocked Progressives for identifying the United States (understood here as a redeemer nation) with the Kingdom of God. In a similar way, politics have been distant from the commemorations of his book. Today’s Protestants are drawn to Machen’s understanding of salvation and the church.

This appropriation of Machen means that a thirst for serious Christianity exists independent from culture war epithets or calls for a political strongman. Ordinary Protestants seem simply to want honest and rigorous discussion of the Bible and its message of redemption. That was what Machen was trying to do one hundred years ago. He saw a church in full support of humanitarianism and uplift that had lost sight of Scripture’s teaching. In response, Machen called for the church to be the church and to step aside from politics. That version of an apolitical church explains again why Machen’s political theology has limited appeal today even though it echoes the point some faculty are making that universities should not issue statements on political controversies but do what they were designed to do—foster debate and inquiry. Without Christians (or other idealists) sticking their righteous causes in the political process, the give and take of a diverse and free society could play out somewhat orderly thanks to constitutional provisions.

If more people noticed all the Protestants reading Machen in 2023, those same observers might rethink the alleged danger that historic Christianity poses to the American Republic.