Eliot Cohen presents a world full of threats, but not all of them are best addressed with military power.

The Consequences of Pious Intervention

Ridley Scott made Black Hawk Down in the spring of 2001. That fall, 9/11 happened, and the movie became a rallying cry of wounded American patriotism and a presage of war. The film’s startlingly realistic and focused depiction of one day of intense fighting proved a success at the box office and with critics both, garnering four Oscar nominations and two wins. It quickly became, as most war movies do, a tool for recruiting and something of a statement on the spirit of the US military.

Twenty years later, it’s a melancholy anniversary: Twenty years of wars that have been fought, fought over in our bitter partisan politics, prolonged inexplicably without prospect of victory, and forgotten by the nation somewhere along the way. Meanwhile, the US military has mostly turned from soldiers to mercenaries, who are still in Afghanistan.

Perhaps we can now look at the movie clearly and learn from its drama: This is a story that honors American soldiers, but it’s far more skeptical about the political decisions that send them to their deaths and the military commanders who come up with clever plans that seem predicated on startling ignorance about the character of the enemies they are fighting. The movie is as clear a warning as possible that what has become the American way of waging war is going to get men into trouble.

Humanitarianism

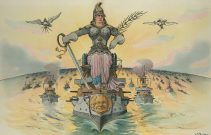

Let’s start with the politics: Black Hawk Down deals with the American invasion of Somalia in 1993, which ended with the military getting its nose bloodied in Mogadishu on October 3, 1993, the day depicted in the movie. Compared to our unending wars, this was a small invasion, and a brief one, but it was also strikingly unpatriotic. It was an act of piety, not war, done with the blessing of the UN, but with no thought to American interests, and, as it turned out, little interest in victory.

Accordingly, the movie stresses the cruelty of the Somali warlord that the Americans have picked a fight with, which was indeed something out of horror movies. Thus, there was a dragon that might call forth American heroism to slay, but that fantasy had little to do with Somalian history. In the late 1980s, Somalia collapsed into a civil war that lasted decades and led ultimately to more than half a million dead, most of them likely starved to death, despite copious quantities of food sent as humanitarian aid. Most of this aid was confiscated by warlords, as the movie both tells and shows us, making the warlords even more powerful over the population, giving them supplies for their own troops and even merchandise to trade for weapons. Humanitarian aid wound up aiding the most tyrannical parties in a bloody civil war. The war continued long after American withdrawal; Somalia is not even today entirely at peace, having broken off into several independent and autonomous pieces. And by the way, there are still several hundred American troops there. Trump somehow heard about it and ordered the troops out, but this seems to have been partly rescinded by Biden.

By 2001, it was obvious that America had accomplished little in Somalia except getting people killed. So the movie, with the aid of hindsight, asks: Did Clinton know what he was doing? The UN? The generals? Why were American men sent to kill people and risk their lives? The movie shows us the shocking arrogance we have since become used to—Washington wants very quick results and is unprepared for setbacks. So instead of waging war, the story is about America staging an abduction to get rid of the warlord, apparently on the assumption that without him peace would be restored. This naïve sentimentality is the rationale for the entire drama we are about to see.

Worse, strategic sentimentality goes together with striking shows of tactical piety pertaining to the UN resolutions that justified and organized the invasion. Most appalling is the liberal morality inscribed in rules of engagement: We see American soldiers waiting to be fired upon before they can engage armed, massing enemies in plain sight; or else they watch helplessly as atrocities are committed, because they are not fired upon. Thus soldiers are drawn into very dangerous situations, but forbidden to wage war, which is, after all, what they were trained to do and the surest way to protect themselves. They are supposed to maintain a peace that doesn’t exist, no doubt for the sake of the international press. A liberal delusion thus creates legal fictions which help not the soldiers, but their enemies—that is the misguided faith the war tests.

Unseriousness

The first half-hour of the movie deals with this setup. The baffling political and military decisions are interspersed with the innocence of the soldiers, who deal as best they can with life in camp and have recourse to humor in order to mock moralistic authorities that are plainly absurd. Then the next two hours show us the horrible consequences. It takes some attention to notice how much criticism of the political-military situation there is in the movie, so we should start simply by asking: Why do these commanders think they can play parent or policeman in a country they know nothing about? The idea that Special Forces abducting one particularly ferocious warlord would somehow dispel the vast numbers of armed men in Somalia was belied by events—by 2001, the man was dead and peace was nowhere near. Common sense would have advised what hindsight later proved: If order has collapsed, the army has turned into gangs of criminals, and there are multiple factions fighting for control, this is not a situation that calls for a police action with Special Forces operators arresting a few troublemakers—this is chaos.

Everyone involved senses that America is unserious. The local warlords don’t feel much fear; the American commanders don’t have confidence; allies aren’t particularly devoted. All of this puts a terrible burden on the shoulders of soldiers.

The movie also teaches us why our rulers were blind to the chaos: Strategic madness is in fact considered tolerable because we rely on technological superiority to get our soldiers into danger and then safely out. Since America wasn’t fighting a real army, it didn’t have to fight a real war. Since it was technologically unchallenged, it couldn’t run into nasty surprises. Since, ultimately, America was the undisputed military power, it couldn’t lose. This is implied by the boredom and amusement of the first act, which leads to a horrific epiphany in the second act, and then desperate fighting in the third. Now, admittedly, helicopters and armored vehicles are mighty weapons, but in urban warfare they are also remarkably vulnerable to much cheaper weapons, especially if the military is under orders not to conquer the city where it nevertheless has to keep fighting. Nor, by the way, were the two Black Hawks shot down on October 3, 1993 the first such losses. Nevertheless, the commanders kept betting on mechanical invulnerability until they lost—and then human beings got killed.

The correlative of the arrogance that comes from technology is a strange squeamishness concerning death, which war is largely about. We already see in this movie that American casualties are considered unacceptable by the very people that make them inevitable. The use of Special Forces instead of the regular military is part of this wish to hide the ugly truth for political purposes—a choice that made it even more difficult to attain worthwhile military objectives, but easier to get into meaningless wars. From the president down to generals, decisions are made that must involve the risk of death—and yet when this happens, an entire crisis begins to unfold, which of course will not hurt them, but the soldiers. This reminds us of the way humanitarian aid merely strengthened bloody tyranny. Appalling as this truth is, the movie shows us without flinching how the desperate hope to save the couple of soldiers in the two downed choppers led to 19 dead, several times more than initially lost, and another 73 wounded, which of course could easily have made the death toll far worse.

Black Hawk Down offers a remarkable picture of this combination of strategic sentimentality, tactical piety, political squeamishness about war deaths, and a baffling eagerness to risk men’s lives when they can’t win. It’s a picture of an America led by arrogant men eager to wield power, not despite but because they are aware of human fragility. The general who stands for American authority is surely a noble man who loves his men and is desperate for their safety—except that he must force them to achieve the impossible without allowing them to fight. Americans are believed to desire an end to all suffering yet also to be eager to inflict suffering when incensed, as for example, by the spectacle of the Somali warlord’s impudent tyranny. This paradox is easily explained by a growing fear that history hasn’t ended and humanity is still tragic. American leaders, therefore, feel they must win and must seem invincible in each engagement, because the enemy would become emboldened by any success, however small. Precisely because America seems to have divine powers, it cannot afford any setbacks which would create doubt that the human condition has changed with the end of the Cold War. At a fundamental level, America has an army it can never risk, so fighting wars is almost an entirely losing proposition—there’s nothing to gain, but the leaders also don’t seem able to stop, because their ambition includes dictating terms in the Horn of Africa and any number of other places Americans know and care nothing about. Therefore, in the face of weak enemies who nevertheless have every reason to fight—life, home, power—the American way of waging war seems woefully inadequate.

So in Black Hawk Down, much like in reality, everyone involved senses that America is unserious. The local warlords don’t feel much fear; the American commanders don’t have confidence; allies aren’t particularly devoted. All of this puts a terrible burden on the shoulders of soldiers who risk their lives in the dangers of urban warfare in enemy territory, where they are hated and feared, where they understand nothing and can trust no one. Essentially, every catastrophe—disasters far worse than tragedies—that befell America in the Middle East was anticipated in Black Hawk Down.

Patriotism and Death

The drama that takes up most of the movie, the initial invasion of the second act and the subsequent defensive fight of the third act, is therefore entirely anticipated. The Lieutenant Colonel in charge of the operation complains to the staff officers briefing him that every circumstance is against them—that they are making themselves incredibly vulnerable—but he still has to obey orders. It’s not that they think he’s a coward or crazy—the movie shows us he is intelligent and fearless in an ostentatious way, standing up under fire while others cautiously hide, getting out of the fight when it is required to save lives, getting back into the fight, despite being wounded, in order to save his men. He is the only officer who never makes a mistake. His character and conduct are not the problem—the problem is that his superiors act as though they have conquered chance, so they don’t need to consider his objections! Perhaps, this arrogance is a secret despair of ever making sense of the chaos of civil war—perhaps they don’t know how they could ever achieve victory, so they’re trying a mad plan, a hope born of that despair. Accordingly, the general goes to send his men off personally and our protagonist lets us know this is an unprecedented gesture. The explanation is simple and ugly: The general feels guilty for a sacrifice he can neither believe in nor prevent.

War, above all, is revealed as the true teacher, an inextricable part of our nature. War is the judge of all the delusions of the post-Cold War era, characterized by irresponsible liberal moralism.

The brutal fighting, however, offers us a real education regarding war, showing us, in the process, that the fake education we saw in the planning stage is hopeless. So the plan changes very quickly from a remarkable victory, a decisive strike to end war, into an ugly, dragging defeat, where the only imperative is the repeated command: “Nobody gets left behind.” This is war reduced to what later became infamous as “exit strategy,” but which is more commonly called retreat.

The ugliness of this defeat comes from the strange fact that the soldiers are almost innocent. The pity of the movie is that their lives are wasted, when they are shown at every step to be competent, alert, and even daring. There is something unspeakably noble in the trust with which these men obey their orders and face their enemies—and in the love with which they fight for each other, trying to save each man, even though they fear they are doomed. Their commitment to each other, their unwillingness to abandon the man next to them to save their own skin, even when they are almost overwhelmed, shows something great about America and about civilization as such. Yet they are more to be pitied than admired, because we know their leaders are eager to forget the hard lessons paid in blood and make the same mistakes all over again.

The power of Black Hawk Down is less in the depiction of handsome, strong young men moving with military confidence and making deadly use of advanced technologies of war—the power of the movie comes from the fear we feel because we know them to be doomed by their commanders, by the politicians, by a way of thinking about war that turns it into a circus. However deadly, it cannot be won, because it is organized according to a philosophical intention to make war as much like peace as possible. Not only is such a strategy unlikely to dispel evil, it also threatens to make greatness impossible. Notice, for example, how few heroes the nation embraces in our times—recognizing in a man’s face and his record of conduct what’s good and great about America.

Much about our nature is revealed in this story, from the moral strength and the competence of the soldiers to the intellectual failures leading to corruption that characterize their leaders, whatever their good intentions. War, above all, is revealed as the true teacher, an inextricable part of our nature. War is the judge of all the delusions of the post-Cold War era, characterized by irresponsible liberal moralism. Somehow, this got even worse when conservatives next took power and doubled down on this moralism at a much larger scale. In noble sacrifice, we see our soldiers’ acceptance of our tragic nature—but are we able to believe as they do that we are worth fighting or dying for? Perhaps that’s why we attempt to put an end to war. I’ll end with the movie’s opening motto: Only the dead have seen the end of war, attributed to Plato—the quote is apocryphal, but the judgment is Plato’s and it is the universal experience of mankind. What more is there to say? We owe our war dead that we act with better judgment and more courage.