Servile Sciences

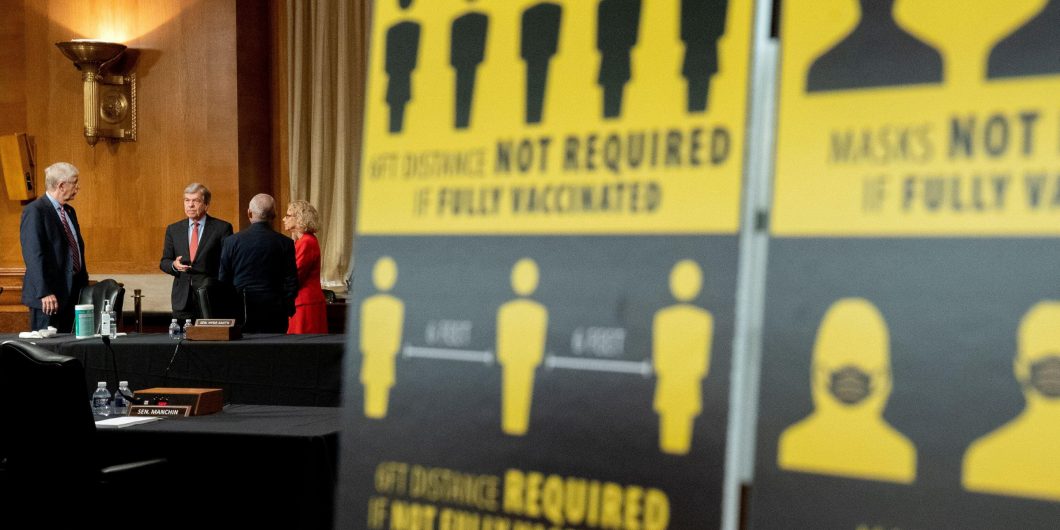

Among the many slogans adopted during Covid pandemic, one that was constantly repeated was “Trust the experts.” The models could’ve been way off, the numbers of cases and deaths completely distorted and misleading, and the remedies for slowing the spread and treating the virus totally counterproductive, but it was important to trust the experts all the same. Undermining the experts could result in people dying.

But what if one who dared to dissent against the supposed scientific consensus of other experts was also an expert? In most cases, it was simply decided that such dissent meant they weren’t experts anymore, and they needed to be silenced along with the rest of the rabble. As the Twitter Files and Anthony Fauci’s emails show, this is exactly what happened to many eminently qualified experts who criticized lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and the refusal to develop cheap and effective therapeutics.

One of the scientists most wronged in this silencing campaign was Stanford professor and epidemiologist Jay Bhattacharya. In October 2020, Bhattacharya coauthored “The Great Barrington Declaration,” which rejected the practice of lockdowns and advocated for a more targeted approach for protecting the vulnerable while working to develop treatments and vaccines. Despite collecting close to a million signatures from scientists and medical professionals all over the world, the GBD was systemically censored on all media outlets and roundly dismissed by government leaders.

However, this was not all. In a recent essay in Tablet Magazine, Bhattacharya relates how he was vilified and ostracized by everyone, not just in government and in the media, but also at his own institutional home. His story is heartbreaking because it reveals just how far the academic institutions have fallen, when calling for an open discussion on public health policy invites such vitriol and abuse from those ostensibly committed to the pursuit of the truth.

Bhattacharya’s story exposes the facade of free inquiry and scholarly debate that is erected by universities like Stanford. Free exchange is especially difficult when research has political uses. In reality, though many professors and scientists might bravely pursue the truth to better their world, they often have to set aside these ideals to get funding from institutions like the NIH, to do their work, and to earn prestige in the academic community. As in other professions, money and political allegiances speak louder than injunctions to work for the common good. This can create a massive incentive against exploring questions that challenge the status quo, thus smothering any semblance of academic freedom.

With their funding and reputations on the line, many of Bhattacharya’s colleagues and friends understandably disassociated from him. Knowing how the system works, he doesn’t really blame them, but he does blame Stanford: “The university’s refusal to defend dissenting voices created an environment in which slander, threats, and abuse aimed at lockdown critics could flourish.” He was made an example for anyone else who wanted to speak out.

Instead of trying to understand how his beloved school declined to this point, Bhattacharya simply ends with a pessimistic conclusion: “Academic freedom at Stanford is clearly dying… members of the public should understand that many of those urging them to ‘trust the science’ on complicated matters of public concern are also those working to ensure that ‘the science’ never turns up answers that they don’t like.” Rather than solve problems and make the world a better place, scientists will increasingly become propagandists who conduct bogus research, publish bogus findings, and create bogus solutions that will only worsen the situation and impoverish Americans.

Considering what happened to him and other eminent scientists, and noting the relative indifference of so many Americans, it’s hard to disagree. But surely, there’s a reason, if not a remedy, for the decline in academic freedom. While Bhattacharya follows the money and mostly blames today’s taxpayer-funded patrons of science for smearing him, this doesn’t go deep enough. The demise of academic freedom has been around for a long time, and its roots are more cultural than financial.

Unfortunately, when the Western intellectual tradition is rejected, it is replaced with a narrow-minded leftist ideology that disparages reason, excellence, and freedom.

As humanities professors Timothy Gordon and Michael Robillard argue in Don’t Go to College, the impulse to stop debate, shut down dissent, and elevate ideologues into unquestionable authorities on scholarship is in some respects a fulfillment of the attack on Great Books that has been going on for decades. Starting in the 1960s, leftist activists and professors protested against reading works of the Western Canon and having classes like Western Civ, on the grounds that they were not adequately inclusive and advanced cultural chauvinism. As it happens, Stanford University was the epicenter of this debate where Rev. Jesse Jackson joined protesters chanting, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western Civ has got to go!”

According to John Agresto in his newest book The Death of Learning, this battle effectively transformed the entire culture of higher learning into something anti-intellectual. Western Civ was more than just a course; it was a symbol of the Western intellectual tradition that extolled reason, excellence, and freedom. This tradition was loudly expressed in the traditional Western Civ class, and along with other humanities courses, it served as the basis for all the other disciplines, including the sciences.

For a long time, the Western intellectual tradition upheld academic standards in higher education. There were fewer mindless appeals to authority (which itself is a fallacy), and rigorous demonstrations of evidence and logic were expectations of serious scholarship. These arguments were in turn challenged by other arguments which would also be supported by evidence and logic. And, as Socrates preached and modeled 2500 years ago, this dialogue between the differing positions would eventually reach a higher truth. This process would play out in scientific debates along with those in art, literature, history, and other areas of study. Even if this didn’t happen, the Western tradition at least provided a means for course correction when discussions became overly politicized or mired in confusion.

Unfortunately, when this Western intellectual tradition is rejected, it is not at all replaced by something better, but rather the opposite: a narrow-minded leftist ideology that disparages reason, excellence, and freedom. Under this system, the servile arts (otherwise known as STEM) replace the liberal arts, standards become relativized, and power dictates what is truth. For those in the humanities, this looks like courses either becoming indoctrination sessions that reward those with the right opinion, versus those who can read, write and think. For those in STEM, this looks like a great scramble to network with the right people and doing grunt work for large financial interests while actual ability and knowledge become secondary.

In truth, it has always been the Western intellectual tradition buttressing both the humanities and the sciences. They were complementary systems of thought that brought out the best in each other.

So when a crisis like Covid demands the response of trained experts engaged in a learned debate, those experts are trained to wait to receive their scripts and follow along. To his credit, Bhattacharya concedes from the outset that he should’ve known better: “Stanford’s motto (in German) is ‘the winds of freedom blow,’ and I would have told you at the time that Stanford lives up to that motto. I was naive then, but not now.”

Nevertheless, when so much work in the sciences is done at the behest of powerful groups in the government or in business, and today’s academic culture treats moral truths as utterly relative, it was really no mystery why most scientists and medical professionals stayed silent. Not only did they not feel any need to speak out, but they also lacked the language to articulate the value of free exchange. Their education has taught them to come to a consensus and provide legitimacy for the people in power like Big Pharma or the federal government—the mark of the servile arts—not to trust themselves or their respective science to challenge propaganda from these authorities—a mark of the liberal arts.

It is likely that Bhattacharya was insulated from the fights about academic freedom because of his status as a credentialed scientist. However, these fights were happening everywhere, and those who espoused heterodox views similarly lost when those who had more power and money eventually silenced them—like the recently dismissed Princeton professor Joshua Katz.

As with the other victims of cancel culture on college campuses, Bhattacharya’s experience once again proves how important it is to restore academic freedom on college campuses. As it stands, college graduates are becoming undereducated sheep, lacking the intellectual tools to produce good ideas, much less refute bad ones (for reference, see Mark Bauerlein’s The Dumbest Generation Grows Up).

In truth, it has always been the Western intellectual tradition buttressing both the humanities and the sciences. They were complementary systems of thought that brought out the best in each other. Take away either of them, and the university’s mission either falls apart or becomes inverted. Without the objectivity and discipline of the sciences, it’s easy to see the humanities falling prey to gimmicks, fads, and worthless virtue signaling. Likewise, without the freedom and critical method of the humanities, the sciences assume the form of dogma that eventually brings about intellectual stagnation, if not outright regression.

Right now, universities in the U.S. and in the rest of the developed world are suffering from the latter problem, as the sciences show troubling signs of decline. Sadly, Bhattacharya’s lament will be repeated for many years until everyone, both inside and outside the university, starts seeing the bigger picture and remembering what the university was for in the first place.