In Indiana Jones 5: The Dial of Destiny, our hero's rugged manliness is reduced to misery, regret, and toxicity.

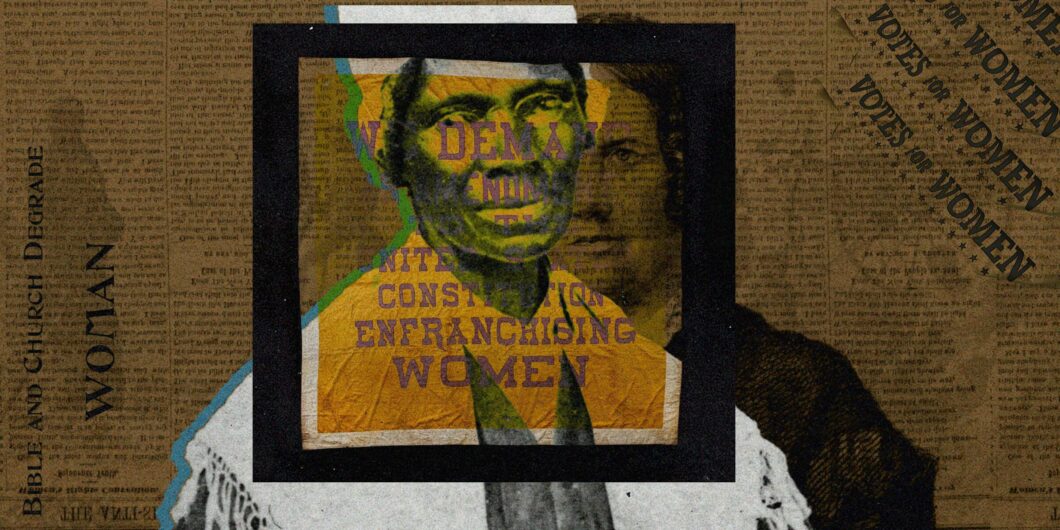

The Truth About Sojourner Truth

In 1828, a former slave named Isabella van Wagenen took her owner to court on the charge that he had illegally sold her five-year-old son out of state. Isabella herself had only been legally free for two years at this point, since New York State was still in the process of phasing out slavery. Those educated by the 1619 project might be shocked to discover that Isabella won her case—one of the first brought by a black woman in the United States—and had her child returned from Alabama on grounds of established habeas corpus rights.

Just about every American has learned about Isabella van Wagenen, albeit by a different name: Sojourner Truth. Truth’s lawsuit is a testament not only to her tenacity, but also to antebellum America’s commitment to justice under the law. However, Isabella has now become a recognized icon of the oppression narrative now used to denigrate American history as too “white,” chauvinistic, and Christian. This is not a casual generalization or exaggeration. Sojourner Truth—particularly her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech—is revered by progressive activists. But as is often the case with historical activism, the account of her famous speech is tarred with falsehoods.

Every American schoolchild for generations has read “Ain’t I a Woman?” The speech is a teacher’s dream: it is short, on-the-nose, and conveniently includes some third-person narration to explain the parts where Truth cows the hostile men in her audience. However, there are two radically different versions of the speech. The most famous one showcases Truth’s unstudied field hand English, evocative of Mark Twain’s Jim with its opening, “Well, chillen, whar dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’kilter!” This is the universally preferred version, included in countless textbooks, classroom syllabi, and even by the National Park Service, although modern editors tend to strip out most of the dialect, and present a more “cleaned up” version.

The other, all-but-completely unknown version of the speech is from Marius Robinson’s newspaper account from three weeks after Truth’s speech at the Akron Ohio Suffragette convention of 1851. All evidence suggests that this version, which does not even include the line, “Ain’t I a woman?” is the closest account of what Sojourner Truth actually said. Robinson’s version is much more self-deprecating and less rhetorically powerful–much more in keeping with extemporaneous remarks made by someone with very little education. While Sojourner Truth was a truly impressive person, she was not an autodidact rhetorical genius as textbooks convey.

Additionally, while the famous fake includes a hostile male audience, complete with witty repartees on the part of Truth, the actual speech was met with almost universal approval and loud encouragement from an ideologically homogeneous audience. As the newspaper record indicates, the witty repartee with angry white male audience members simply did not happen.

Behind the famous fake is a prominent white feminist of the nineteenth century, Frances Dana Barker Gage, who wrote “Ain’t I a Woman?” twelve years after the fact. One of the organizers of the 1851 Ohio convention, Gage included her account of Truth’s speech as an example of feminist and abolitionist rhetoric in an anthology intended to revive interest in women’s suffrage during the Civil War. Ultimately, Gage hijacked Truth’s voice in order to advance the idea that women—including upper-class white women—were the most “enslaved” inhabitants of America. As Gage’s friend Susan B. Anthony would claim, “[Frederick] Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.”

In order to harness the zeitgeist of anti-Southern sentiment for her own purposes, Gage recast Truth as a “breeder” of slave children with no legal recourse–a victim of systematic chauvinism. While Truth had only five children (not a high number in the 19th century), Gage egregiously inflated the number: “I have borne thirteen chillen, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard!” In reality, Jesus’ was not the only receptive ear to her mother’s grief: He was joined by the New York state Supreme Court that granted her son habeas corpus. In fact, in Robinson’s more accurate version, Truth never mentioned her children, who were, by this point, long free. However, it served Gage’s own purposes to depict Truth as utterly defenseless–sexually and legally. That a woman–and a black woman at that–had found justice in the American legal system was not a beneficial talking point.

Gage also depicted Truth as a southern field hand, radically altering Truth’s speech patterns, making stereotypical use of a southern black dialect her readers would have instantly recognized from emotionally-jarring works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In actuality, Truth would have spoken with a Dutch accent–her first language in her home state of New York. Here, too, Gage was engaged in crafting a deliberate talking point: “I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me!” Gage has Truth proclaim. “I could work as much, eat as much, as a man…and bear de lash as well.” However, not only was Truth not a Southern slave, but during her time as a slave, she was tasked with one of the most iconically feminine tasks of all: spinning wool.

Interestingly, the fifty-something-year-old Truth’s bluster about surpassing men in her physical capacities is one of the only parts of Gage’s version that effectively matches the original in style and substance–suggesting that Gage had access to the newspaper account (or more faithful notes of her own) while writing her famous fake twelve years after the fact. Robinson recounts Truth as saying, “I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.” Unlike some of Truth’s other arguments, this was a useful theme for Gage to continue. Well-bred upper-class white feminists of the day could hardly claim feats of physical strength like Hollywood depicts in today’s action heroines. But the racial stereotyping of the day made the idea of a brawny black woman more palatable, blurring some of the otherwise obvious distinctions between male and female capabilities and the resulting implications about gendered differences.

Thanks to Gage and her political agenda, Sojourner Truth’s actual speech has been deliberately buried for 172 years.

What Gage edited out of the speech is also significant. In her account, she depicts Truth making a brief argument about intellectual capabilities: “If my cup won’t hold but a pint and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have a little half-measure full?” In Robinson’s version, Truth adds quite a bit more: “You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.” The actual Sojourner spoke from a position of restraint and self-deprecation, without aggression towards men. Robinson’s Truth spoke with a friendly laugh; Gage’s Truth angrily scolded and denounced. This is significant, as Gage consistently recast Truth’s words to ramp up bitter antagonism between the sexes.

The latter half of both versions turned to religious arguments. The key difference is that the actual speech did not embark upon an attack on Christianity and organized religion. Gage, by contrast, populated her imaginary audience with literal religious villains. In the fictional account, the speaker addresses the objections of clergy who are present: “Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can’t have as much rights as man ’cause Christ wa’n’t a woman. Whar did your Christ come from? Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman. Man had nothing to do with him.” Robinson’s reported version, on the other hand, merely says: “And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part?” So Gage inserts her mocking strawman of Christianity’s conception of gender differences—and, with the repeated emphasis on “your Christ,” Christianity itself, all while sneering at the “little” men completely absent in Truth’s actual audience.

Many early feminists were deeply critical of traditional Christianity. For instance, Gage’s good friend, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was an ardent supporter of a fully secularized government and went so far as to pen her own “Women’s Bible,” which rejected almost all of Judeo-Christian theology:

Marriage for [women] was to be a condition of bondage, maternity a period of suffering and anguish, and in silence and subjection, she was to play the role of a dependent on man’s bounty for all her material wants, and for all the information she might desire on the vital questions of the hour, she was commanded to ask her husband at home. Here is the Bible position of woman briefly summed up.

In placing this same attack on Christianity into Truth’s mouth, Gage emphasized the growing rejection of biblical teaching on gender among early feminists. Gage has Truth conclude, “If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all her one lone, all dese togeder ought to be able to turn it back and git it right side up again, and now dey is asking to, de men better let ’em.” The aggression is palpable in its insistence upon female power–Gage even manages to spin the Fall into a moment of women’s strength. This idea of women having the power to get the world “right side up again” was a favorite of Gage’s, who wrote the sanctimonious hymn entitled, “One Hundred Years Hence.” In Gage’s vision of feminist utopia, laws would become “uncompulsory rules,” prisons “converted to national schools,” and human morality so altered for the good that war, oppression, and vice would be eradicated, all thanks to the voting power of women.

The approach Truth takes in the Robinson version, by contrast, is much calmer, suggesting a woman uninterested in uprooting biblical concepts or in spreading acrimony and blame between the sexes. “I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again.” Here she accepts the biblical account that depicts the first woman as culpable for the Fall. She does not angrily call out men for standing in her way.

The Robinson account of Truth’s speech continues, “The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept–and Lazarus came forth.” Truth’s piety handles the biblical accounts with more sympathy, simply reminding her audience of Christ’s acceptance of women.

Thanks to Gage and her political agenda, Sojourner Truth’s actual speech has been deliberately buried for 172 years. The need to turn Truth into an icon of female and minority victimization at the hands of a white, male, Christian citizenry has shaded out her–and the American legal system’s–triumph of justice in 1828 when her son was returned to her from the Deep South. Even those educators and historians who know about the famous fake’s dubious origins tend to remain silent and allow this blatant historical falsehood to continue to shape their preferred narrative of America. For that cause, Truth–and the truth–continue to be expendable.